American Colonial Revival:

Making the Invisible Visible

Making the Invisible Visible

The American Colonial Revival is a longstanding manifestation of object-based U.S. cultural nationalism. This complex cultural phenomenon, succinctly described as “national retrospection,” began soon after the founding of the United States and has persisted ever since. Ostensibly peaking between 1880 and 1940, the revival takes many forms, encompassing decorative arts, architecture, landscape design, painting, sculpture, graphic arts, literature, photography, and film. Key practices include forming collections, staging commemorations, and preserving historic sites. Situated within the oft-cited historical context of industrialization, urbanization, and immigration, the Colonial Revival intersects discourses of regionalism, romantic nationalism, nativism, progressivism, modernism, and antimodernism. Further points of consideration include the relationship to the Arts and Crafts movement and comparable revivals in the Americas and Europe.

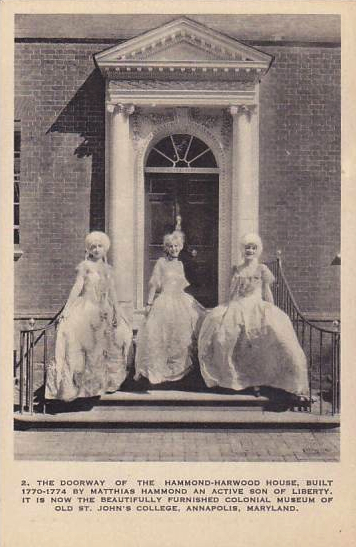

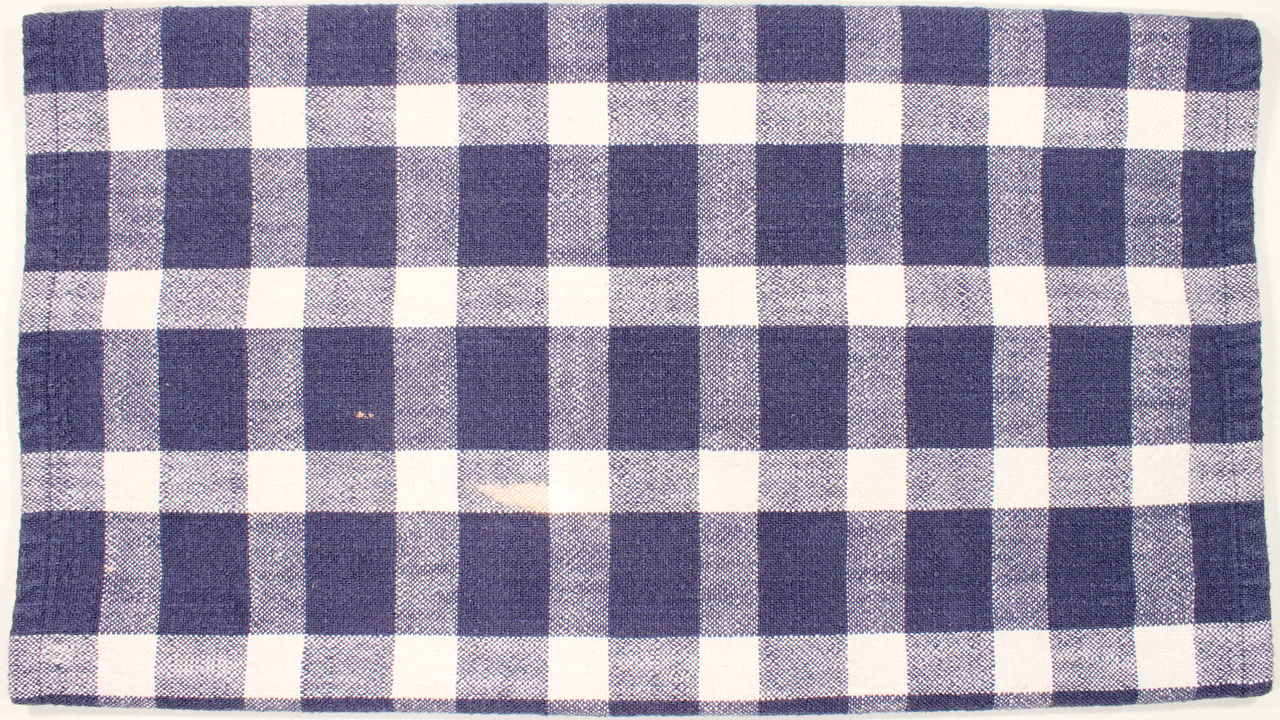

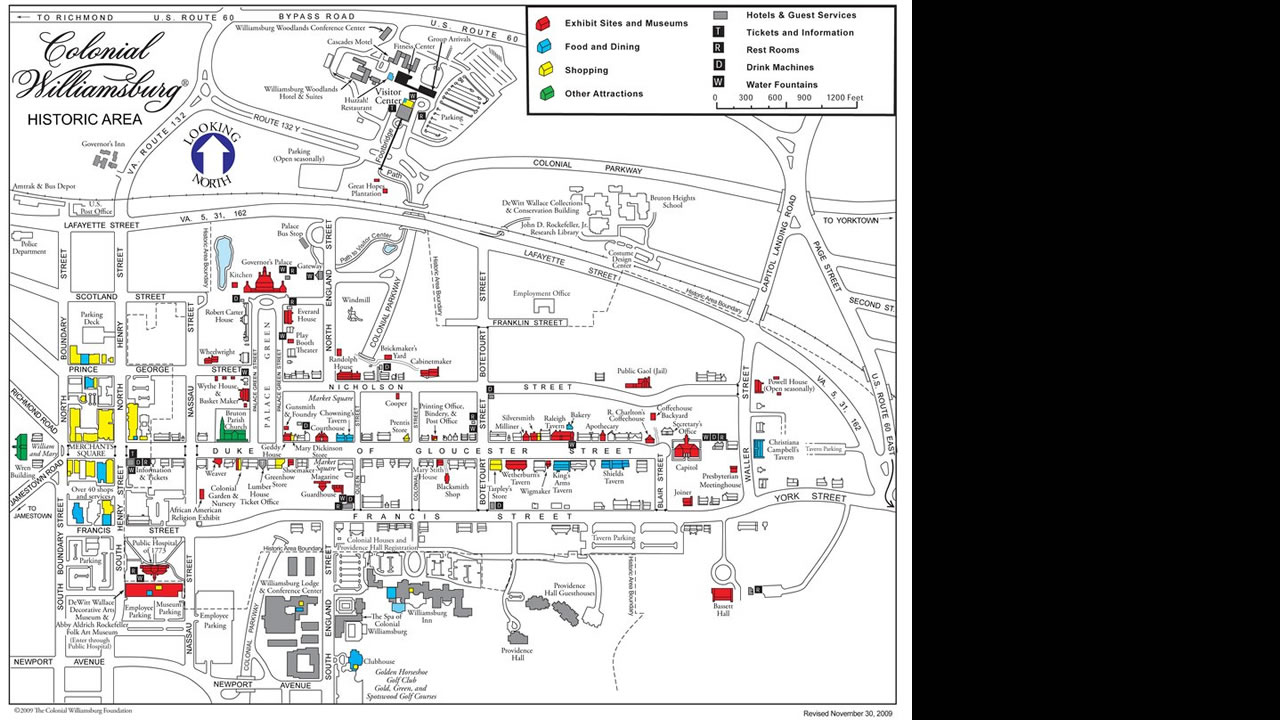

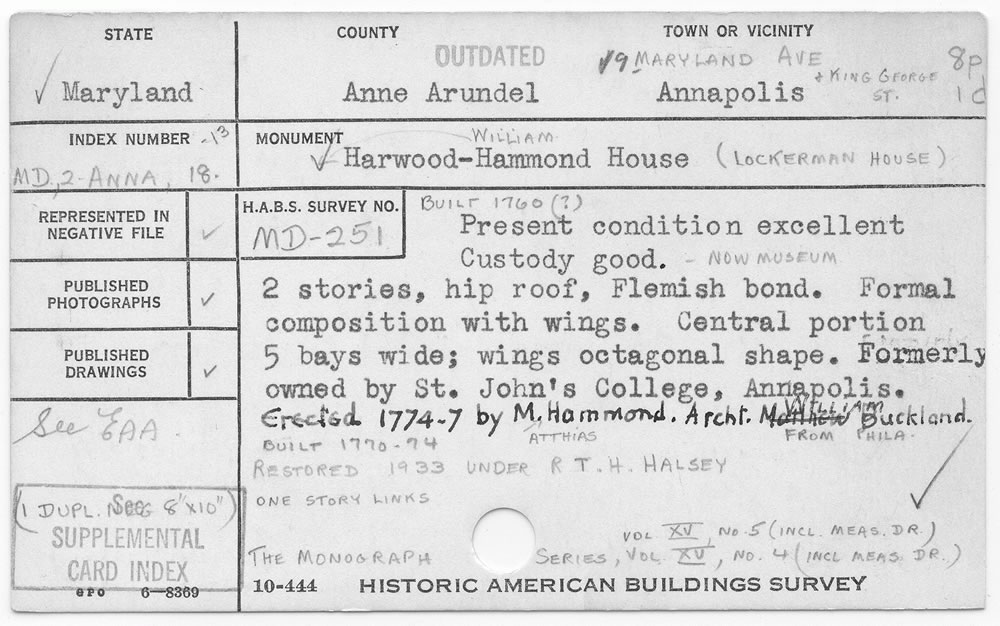

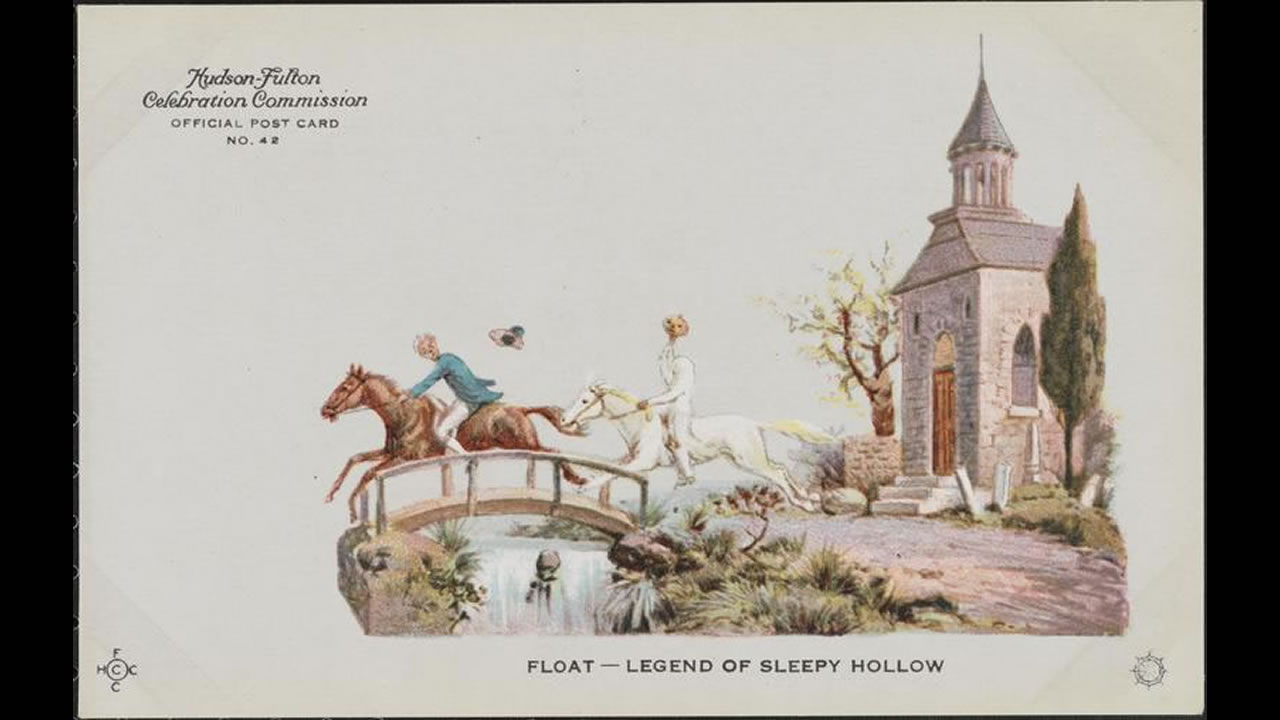

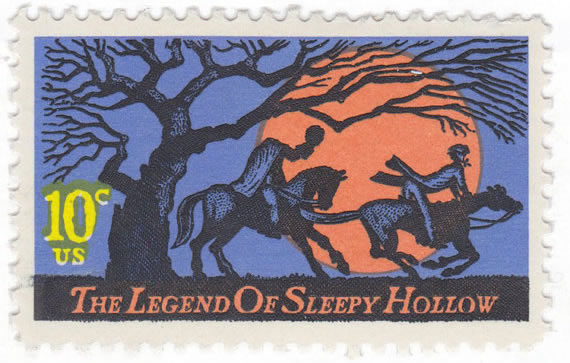

In the United States, artifacts that reference early America are so ubiquitous that they are taken for granted, often going unnoticed. The goal of this project is to make this ‘invisible’ material culture visible through case studies of five objects, purposely varied in date and form. They are ordered from the most recent to the most historically distant, working back from the present day to the earliest encounters among Native Americans and Europeans. The given dates pertain to when these things became ‘colonialized’, which are not always the dates of their making. They range from a c. 2013 reproduction textile sold as a napkin at Virginia’s Colonial Williamsburg; the Palladian doorway of the Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis, Maryland, which was built 1774-77 and became a historic house museum in 1940; a c. 1898 Tiffany silver tea and coffee service; Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” a work of gothic fiction from 1820; and the indigenous plant ‘Indian corn’, so dubbed by an Englishman in 1604.

To use the site, scroll down through the case studies, or use the top bar menu to jump to a particular object. On the far right is a pull-down menu of shared interpretive themes: the power of evocation, the articulation of temporality, dynamics of cultural and economic value, the politics of making, gender and material culture, and belonging. The up-and-down arrows jump to the sections of each case study that pertain to that theme.

Colonial Williamsburg Check Napkin

Using that napkin reminds a person of his or her own personal experiences visiting the museum, and also calls to mind a past in which such an item was in use The Colonial Revival is well in evidence at a museum like Colonial Williamsburg, which celebrates early American heritage and is a trend setter of colonial revival style.

Colonial Williamsburg has at its heart a mission of education, but still operates on a business model of creating a product for the consumer. The product may be historic activities and programming, or physical goods for sale. The interpretation within the Historic Area, whether first person reenactment like Revolutionary City or the re-creation of historic trades, stages an experience for the audience. The programming is informed by the public, based on perceptions of what the public wants to see, but also what the museum administration feels the public needs to know. The other products created by the museum are the items stocked by the gift stores or goods stamped with the Williamsburg brand sold by several retailers.

Colonial Williamsburg has invigorated the Colonial Revival since its foundation. It began with the vision of Reverend W. A. R. Goodwin (1869-1939) and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (1874-1960). In 1926, Rockefeller began buying properties along the Duke of Gloucester Street and restoring them to their eighteenth-century status. Rockefeller reflected on the project saying:

The restoration of Williamsburg offered an opportunity to restore a complete area and free it entirely from alien or inharmonious surroundings as well as to preserve the beauty and charm of the old buildings and gardens of the city and its historic significance. This it made a unique and irresistible appeal.

As the work as progressed, I have come to feel that perhaps an even greater value is the lesson that it teaches of the patriotism, high purpose, and unselfish devotion of out forefathers to the common good.1

Williamsburg Trades/Education

From the earliest stages of the museum’s development, the interpretation of historic trades was a high priority. Once the buildings were restored, they began to be filled with the objects and people who would have inhabited them, including the craftspeople expertly plying their trade with eighteenth-century methods. It was believed that this craft revival would interest visitors, allowing them to see how the decorative objects that were part of the popular colonial revival style were made using hand-crafted methods.

Reproduction Program

Colonial Williamsburg has greatly inspired the colonial revival style in architecture, gardens, furniture, and decorative arts. Reproductions were first used to fill the preserved homes and stores in the Historic Area. Guests responded positively to the decorated rooms, and were soon asking how they could purchase these types of goods. A whole issue of House and Garden (November 1937) was devoted to Colonial Williamsburg, and public interest in its history and the desire to own the designs that they saw there. The reproduction program was an early part of Rockefeller’s involvement with the museum. One of the first products made was chinaware produced by Josiah Wedgewood & Sons based on architectural fragments, designed to stand up to modern use in the Raleigh Tavern. Rockefeller then suggested that "the purpose of education might be furthered by the sale of this ware.”2 Thus the sale of authentic reproductions was instated, which grew to include furniture, textiles, wallpaper, pewter, brass, carpets, lighting fixtures, pottery, and paint.

The process begins by first consulting the Department of Archaeology, to learn if fragments have been found at a given location. A study is then made of the collection and generally two or more similar items are selected initially. The manufacturer then studies the items. Often, handwork or techniques used in the original are not practical for a reproduction because tools, and even materials, have changed throughout the years. Once the article has been agreed upon, it must be thoroughly documents as being of the period. The object is then carefully studied and followed during the reproduction process. Many accumulated and specialize techniques are employed in reproducing each article.4

Once the object is completed by the manufacturer, it is presented for approval to Colonial Williamsburg’s Products Review Committee, which include among its members the directors of archeology, research, and collections. The whole process can take over a year to ensure that the product is up to the quality and educational value of Williamsburg’s standard.

The other types of manufacturing Colonial Williamsburg engages in are adaptations and interpretations. Adaptations are items that have been altered to fit modern taste, such as the coloring of wallpaper and textiles, or adding size variation. Interpretations are souvenir items, which although not historically authentic, serve as a reference to a visit to Colonial Williamsburg, such as mob caps, tri-corn hats or commemorative cards and kits. These items can be produced in a larger quantity, and at less strenuous quality certifications than reproductions or adaptations.

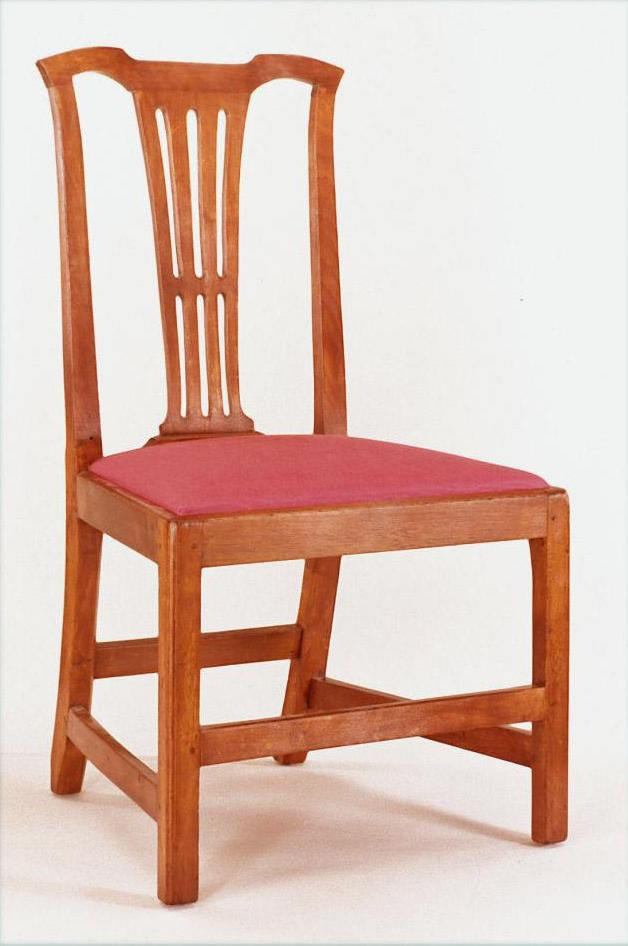

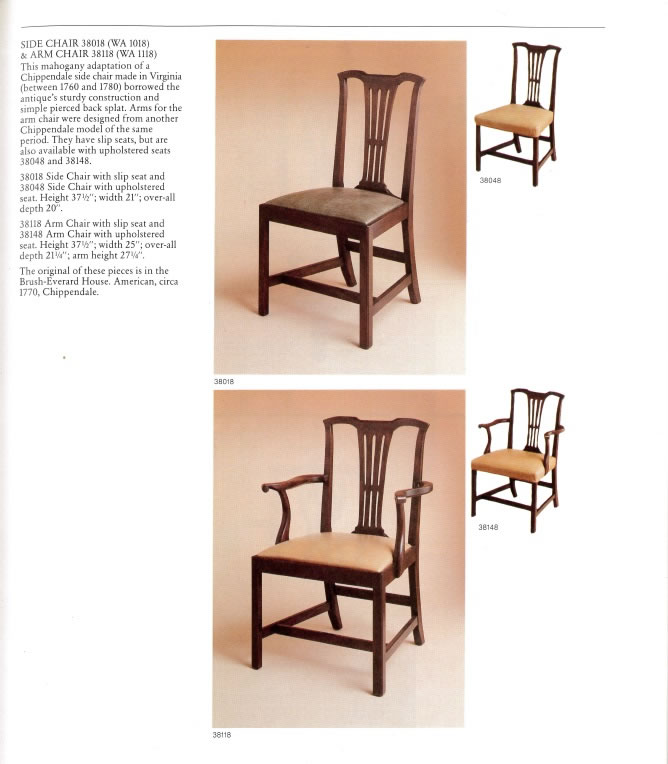

For instance, in the images below, the chair on the left is the original object from the collections, dating ca. 1770 from New Hampshire. On the right is the advisement for a reproduction of the same chair. The lower picture in the ad shows an example of an adaptation, where the arms of a different Chippendale chair were added to this one.

Right: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Williamsburg Reproductions. Craft House, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1982

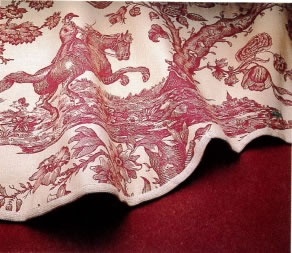

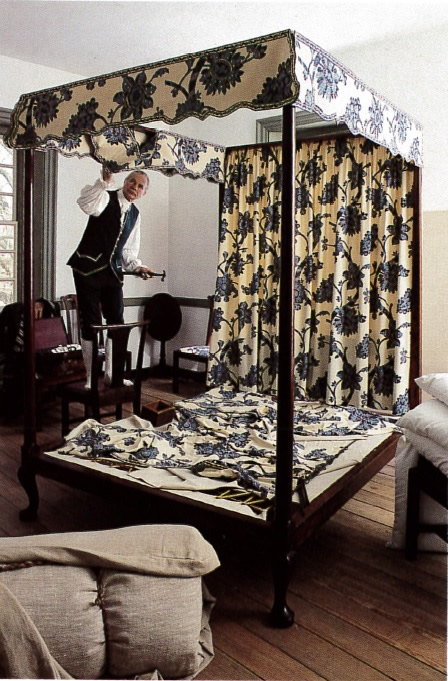

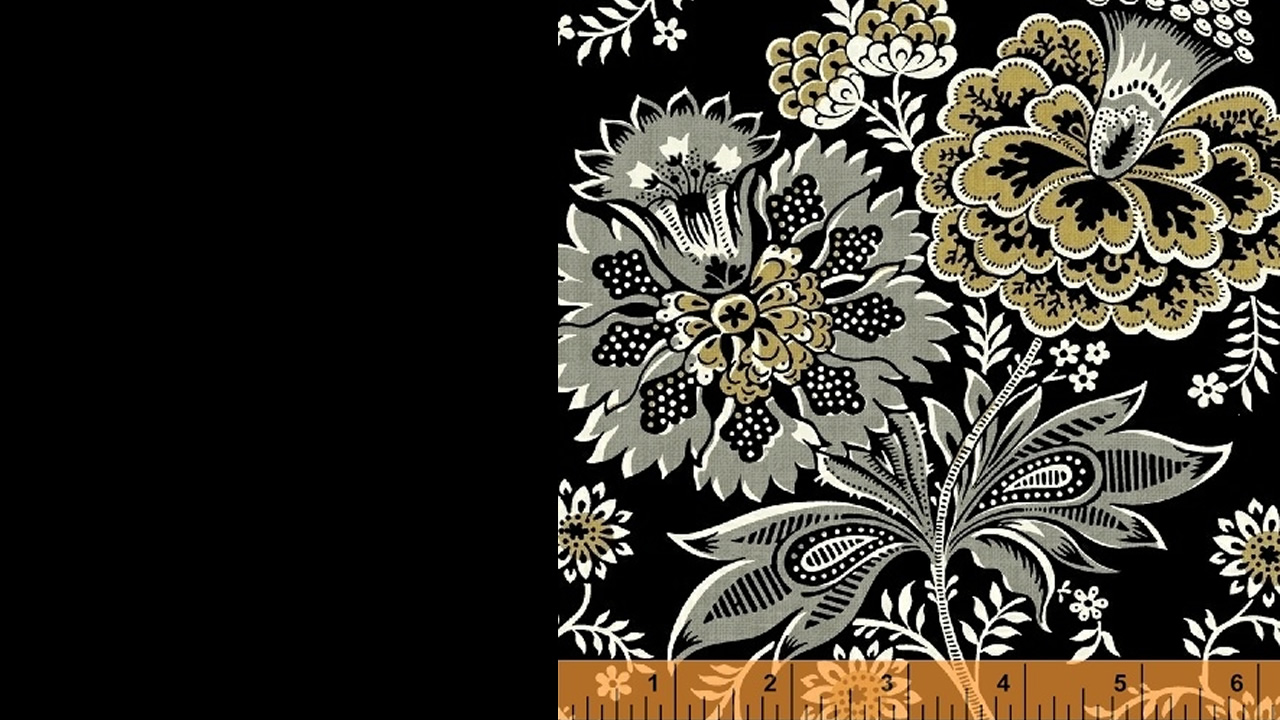

In the next comparisons shown below, the textile as seen in the historic area is shown on the left, while the images on the right show how the textile is advertised as a reproduction.

Right: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Williamsburg Reproductions. Craft House, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1982

Right: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Williamsburg Reproductions. Craft House, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1982

Since the 1990s the Craft House has focused more on smaller decorative arts items rather than large furniture reproductions. There are several stores in the Williamsburg Marketplace that offer different types of coloniallyinspired goods. The Craft House creates high quality items of pewter, fine ceramic giftware, folk art, and jewelry. Williamsburg At Home® offers “home furnishings and accessories including furniture, bedding, rugs, lighting, dinnerware, flatware, glassware, prints, fabrics, and decorative accessories.” Williamsburg Celebrations™ offers “holiday decorations, collectibles, seasonal floral arrangements, and garden accessories galore” inspired by Williamsburg’s Christmas decorations, as Christmas is consistently the most popular visitation time of year. Everything Williamsburg and Williamsburg Revolutions provides souvenir goods “from T-shirts to tavernware to toys…and exclusive Colonial Williamsburg logo products.” Williamsburg also continues to work with external companies to create products that are licensed to carry the Williamsburg Brand, and meet the demand for colonial-inspired items.

Style in Decorating

Descriptions of the products from the reproduction program not only use ‘timelessness” to sell their products, but also evoke memory and nostalgia. In elevated language, the 1973 edition of the Craft House publication compares the materials and craftsmanship that goes into their reproductions. They claim that “there are no memories in foam or plastic,” critiquing modern and post-modern styles of contemporary America. Instead they describe their products as “the desks and cupboards, the draft-proof wing chairs, the expanding dining tables that furnished the homes of our Founding Fathers planned and built and fiercely defended. It is glorious décor…and considerably

more.”6 The promotional material suggests that honesty in design and the materials of the eighteenth century are missing from contemporary manufacturing. It also invokes the Founders to draw upon the emotions associated with them and link them with the Williamsburg products–emotions such as patriotism, hard work, and handcraftsmanship.

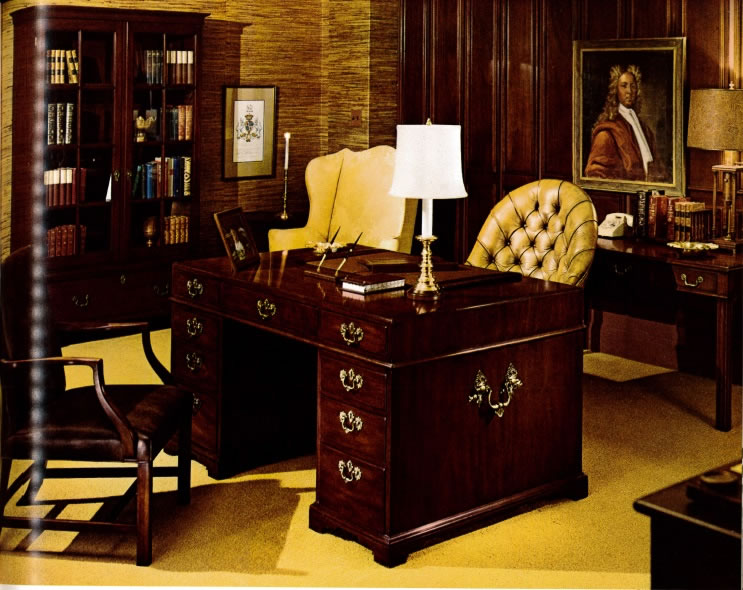

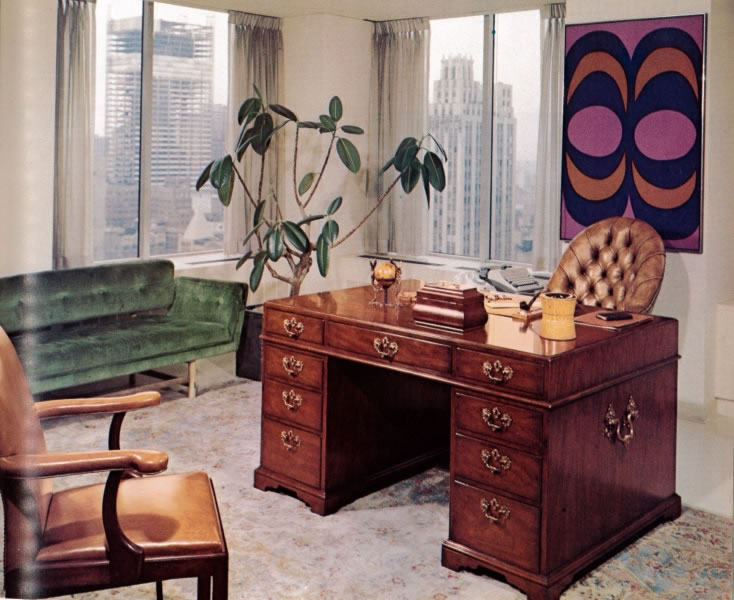

The Partner’s Desk, reproduced from a desk in the Governor’s Palace, is photographed in two settings in the 1973 Craft House catalogue. On the left it is situated in a colonial revival style office, while on the right it appears in a modern 1970s office. Showing the same piece in two contexts is a way that Williamsburg can demonstrate how colonial revival furniture can fit into any décor with a “timeless quality.”

In the Colonial Williamsburg area, there is one home decorated specifically in the colonial revival style. Bassett Hall, located a block away from the Historic Area on Duke of Gloucester Street, was the home of the Rockefeller’s in the 1930s and ‘40s. Unlike the rest of the Historic Area, which aims to transport guests back to the eighteenth century, it is decorated to reflect the early days of the restoration of Williamsburg. In this Hall, the visitor can see the colonial revival style, and travel a few blocks down and see the inspiration for it in the restored homes.

Tourism

Conclusion

Goodwin and Rockefeller wished to restore Williamsburg to represent the town when it was most active and important, in order to remind Americans of their celebrated past. Williamsburg has contributed to the mythologizing of the American Revolution and the founding generation. They have encouraged visitors to bring Williamsburg’s patrimony into their homes by decorating in the colonial revival style, in an attempt to associate idealized principles with domestic decorative arts. But Williamsburg was not only a stylistic trendsetter, but also a leader in education and research. In response to its longstanding role in mythologizing America's origin, the Foundation today strives to challenge those myths by presenting more accurate and diverse versions of the story. Their reputation for authenticity in their crafts and interpretation is what has made them one of the most trusted sources of colonial history, which other museums and institutions must measure themselves against.

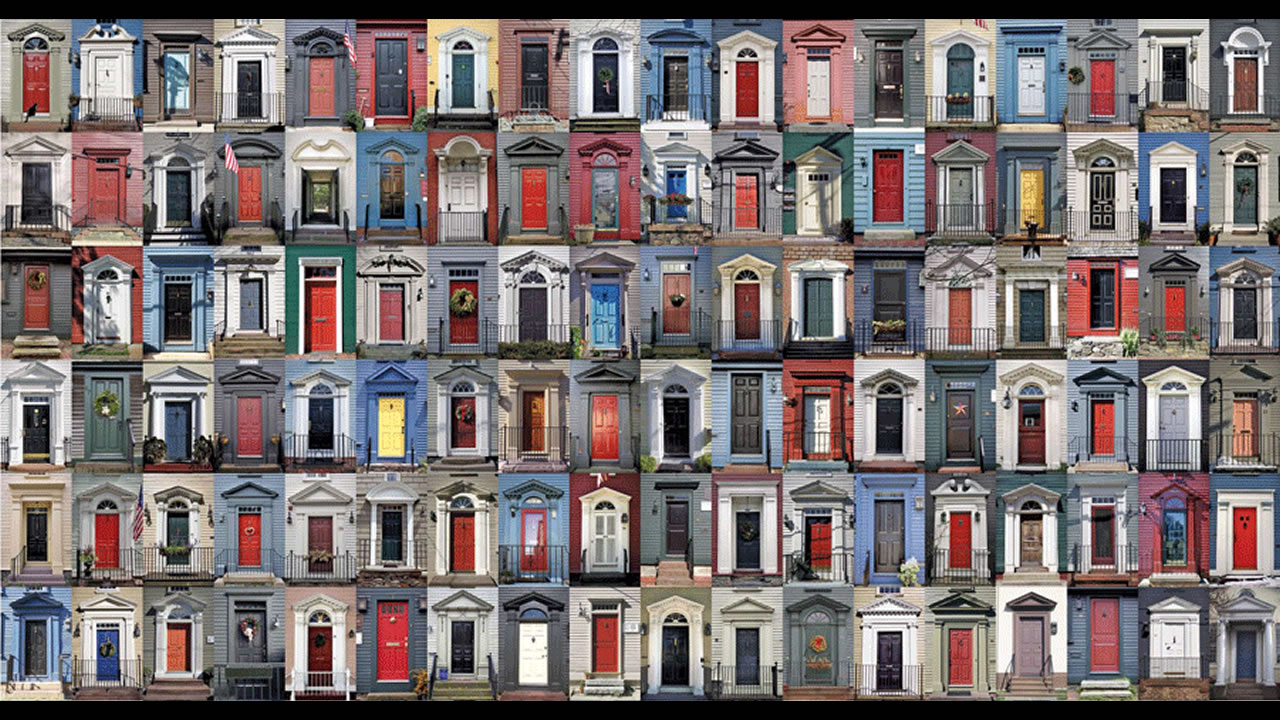

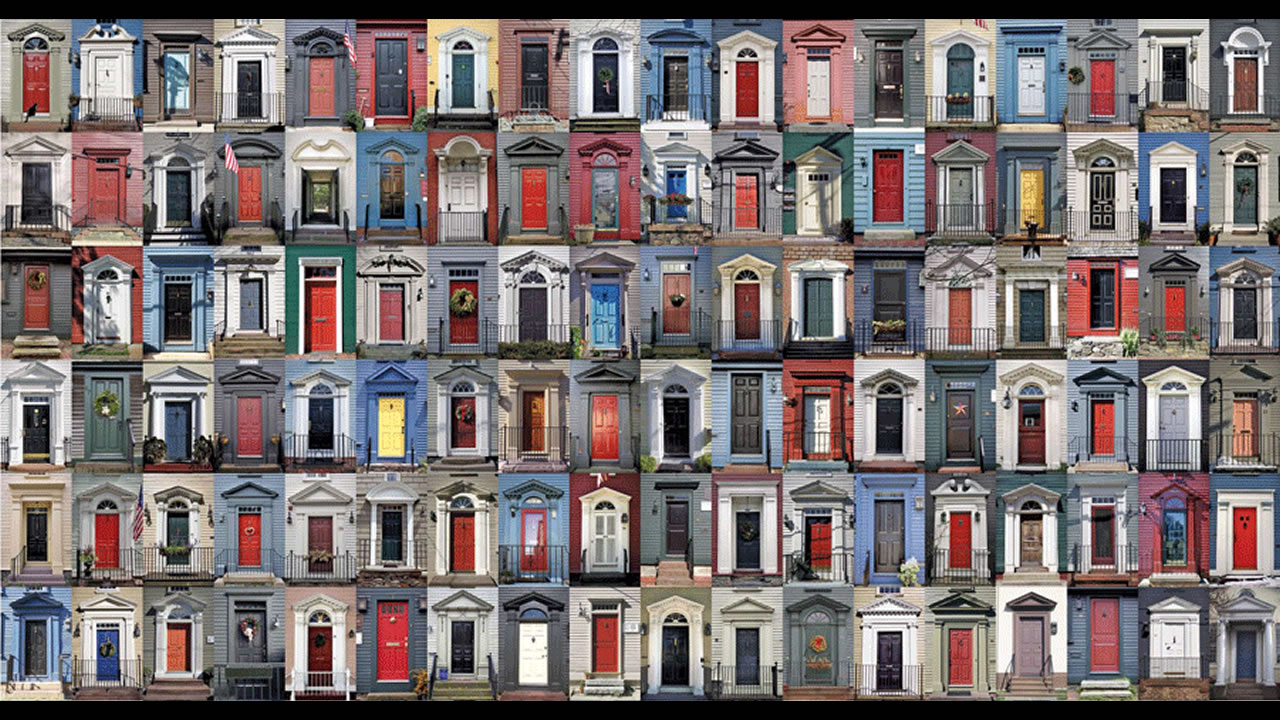

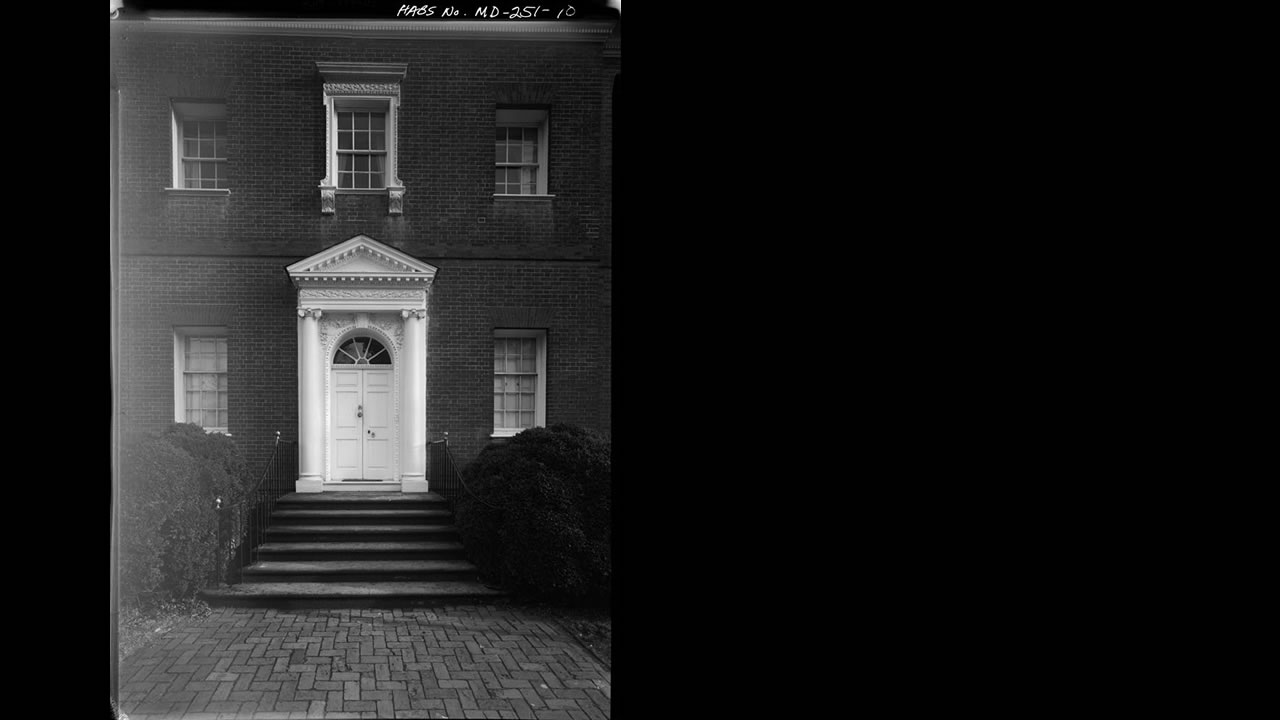

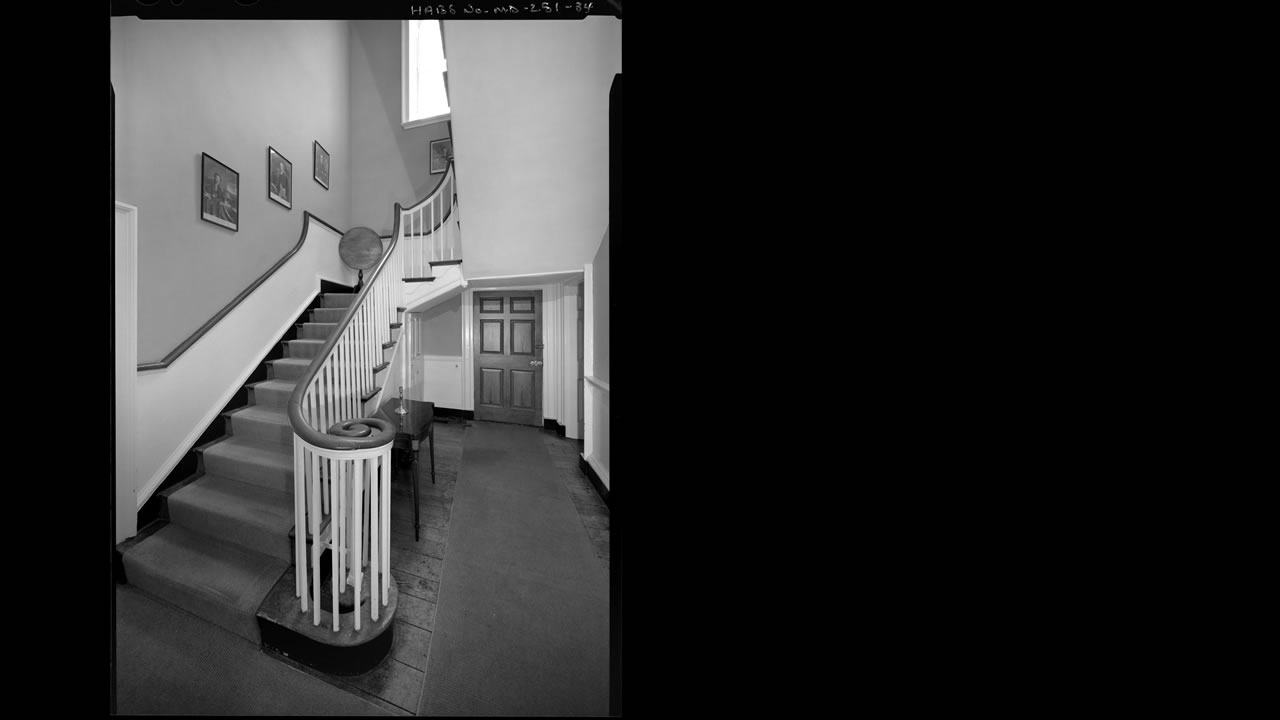

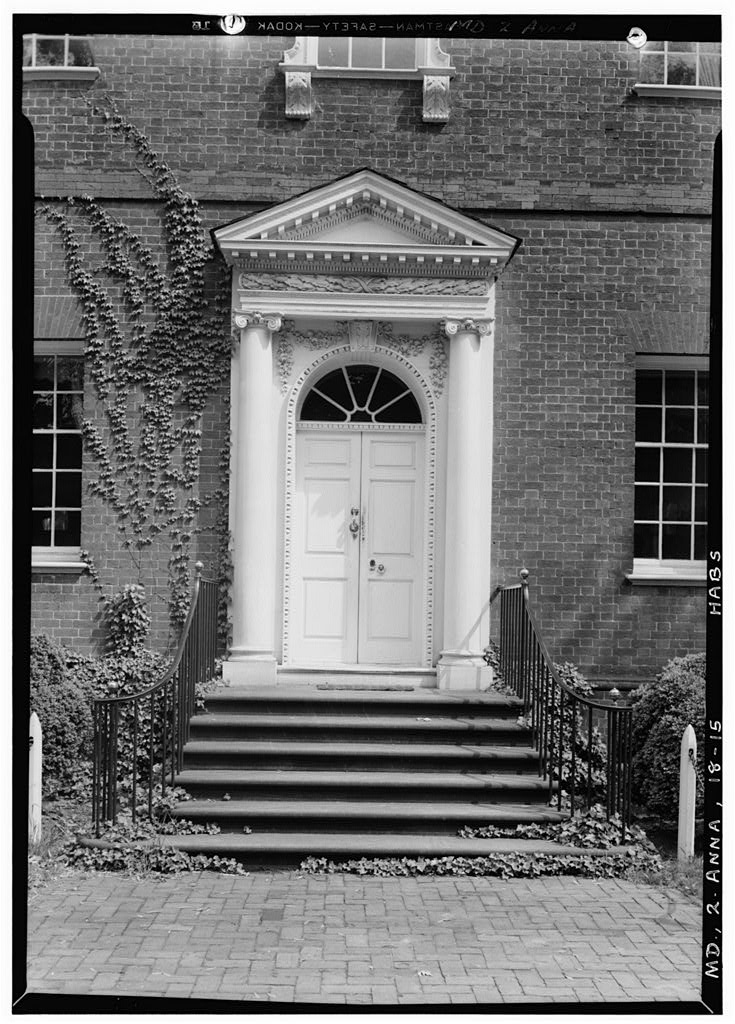

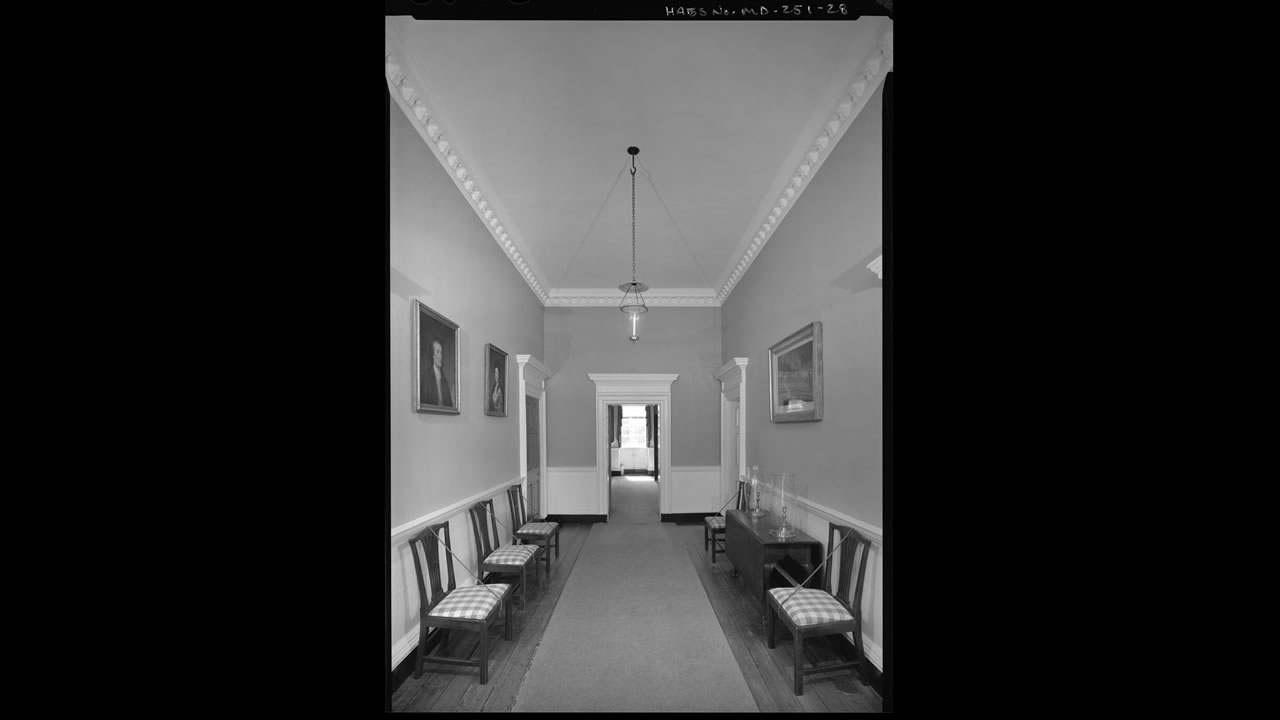

The doorway of the Hammond-Harwood House once separated a domestic interior from a public exterior. Since 1940, when the house became a public museum, it has acted as a portal connecting the past to the present.

What is a door? What is a doorway?

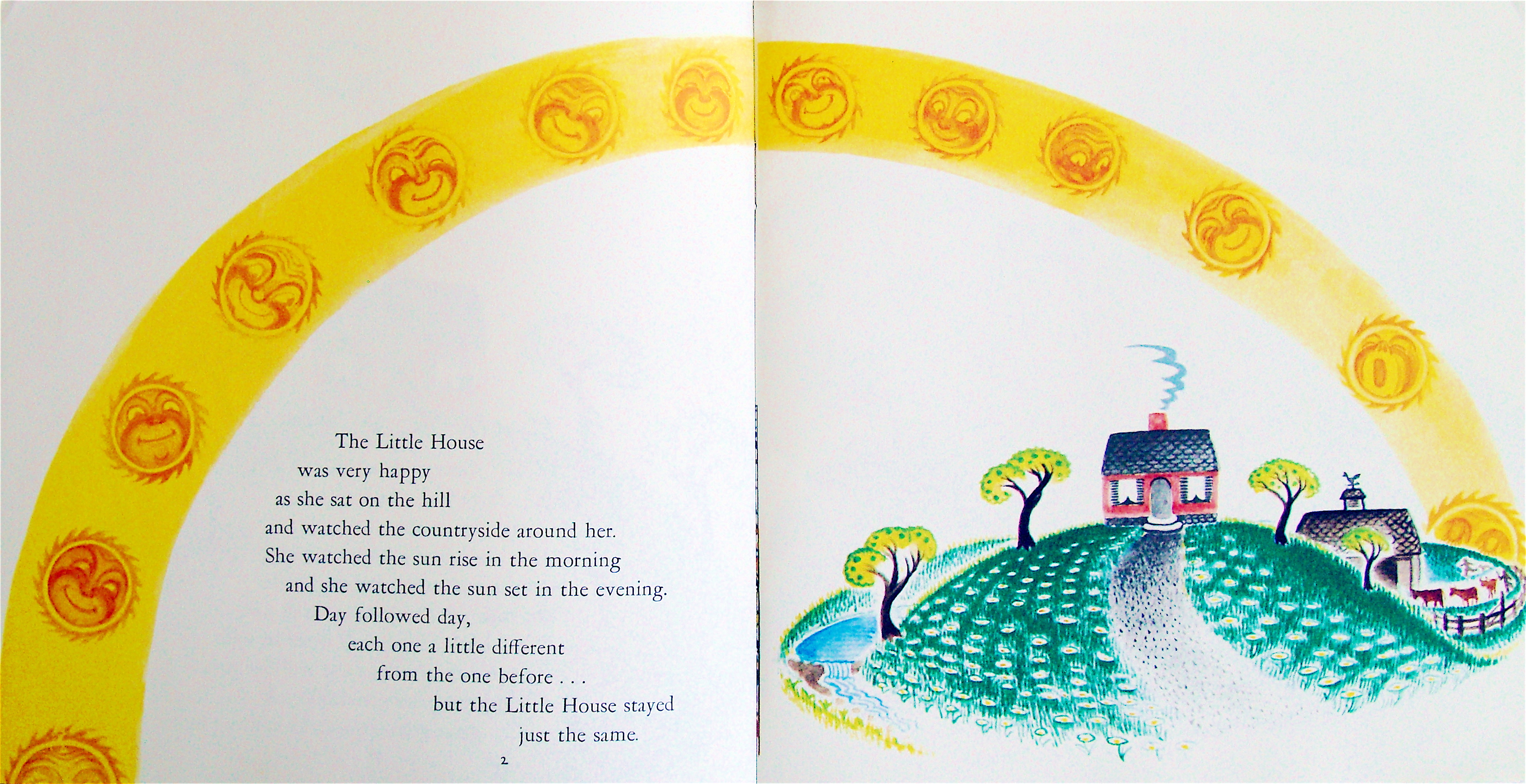

The preservation of a house, of a home, often endeavors to personify and iconize the building. Such has been the case with the Hammond-Harwood House. The difference between The Little House and Hammond-Harwood house (besides scale) comes down to a distinction between formal and charismatic qualities.

Style: The Hammond-Harwood House and Its Doorway

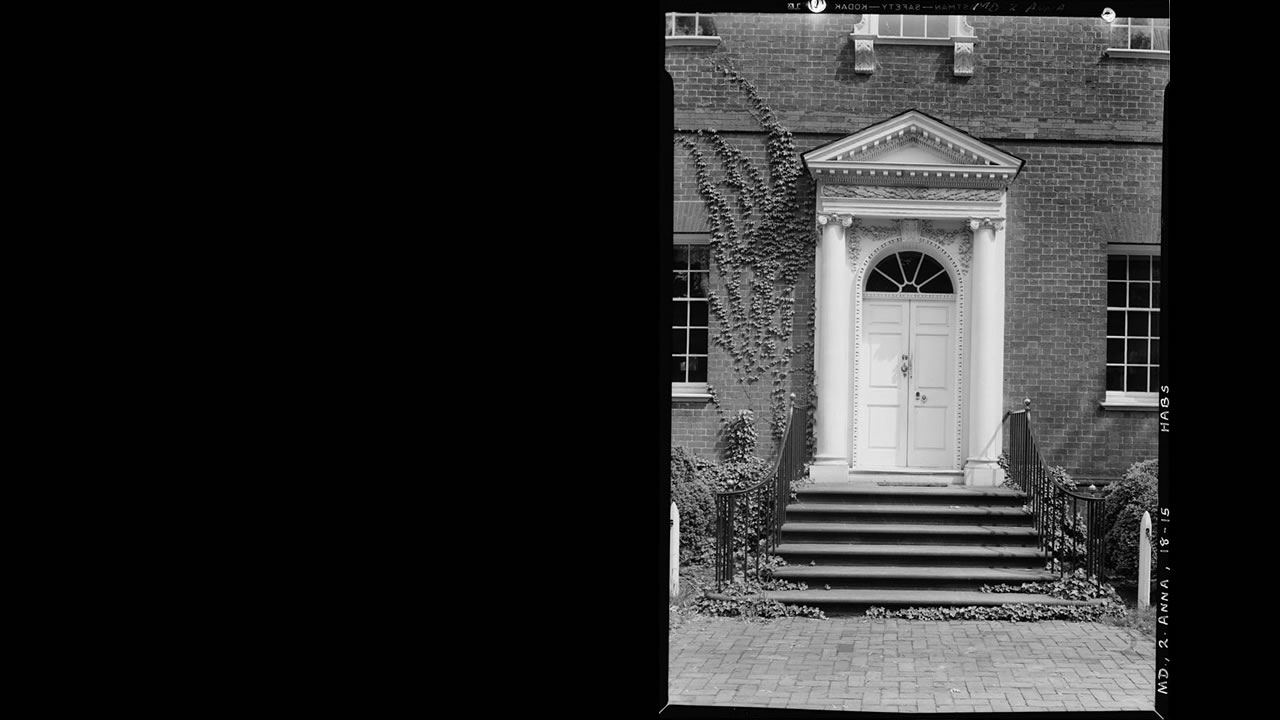

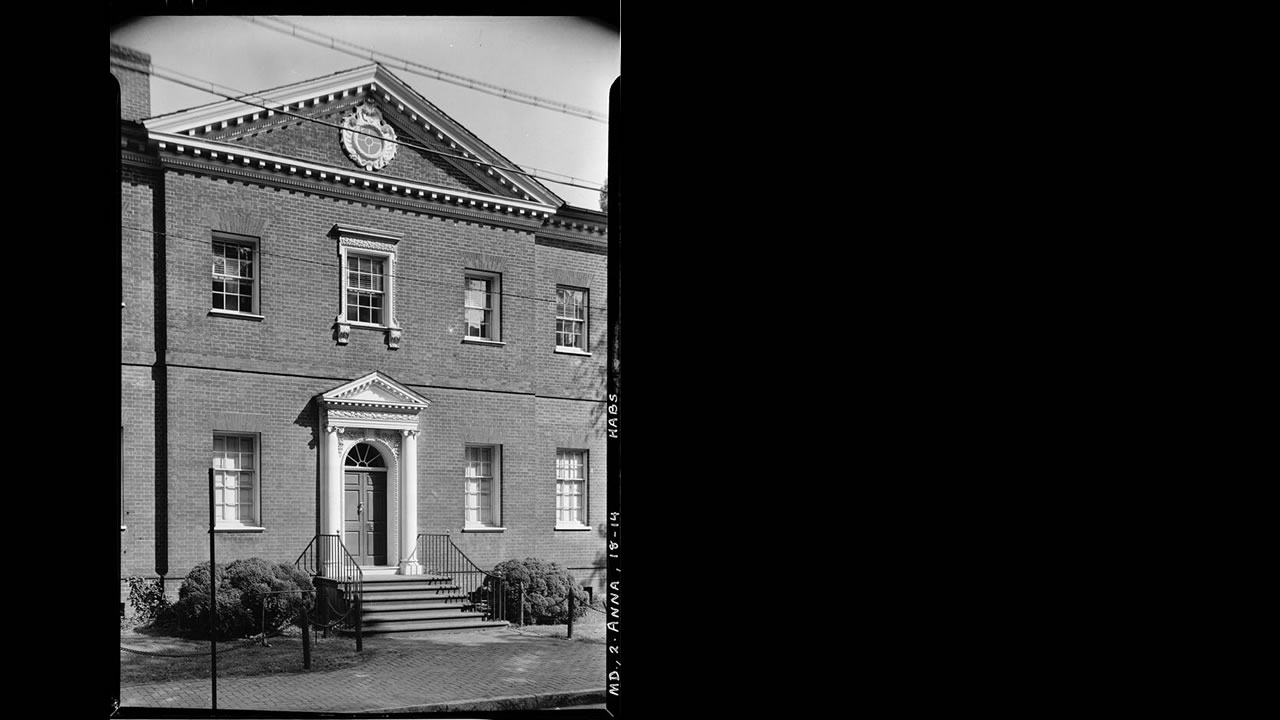

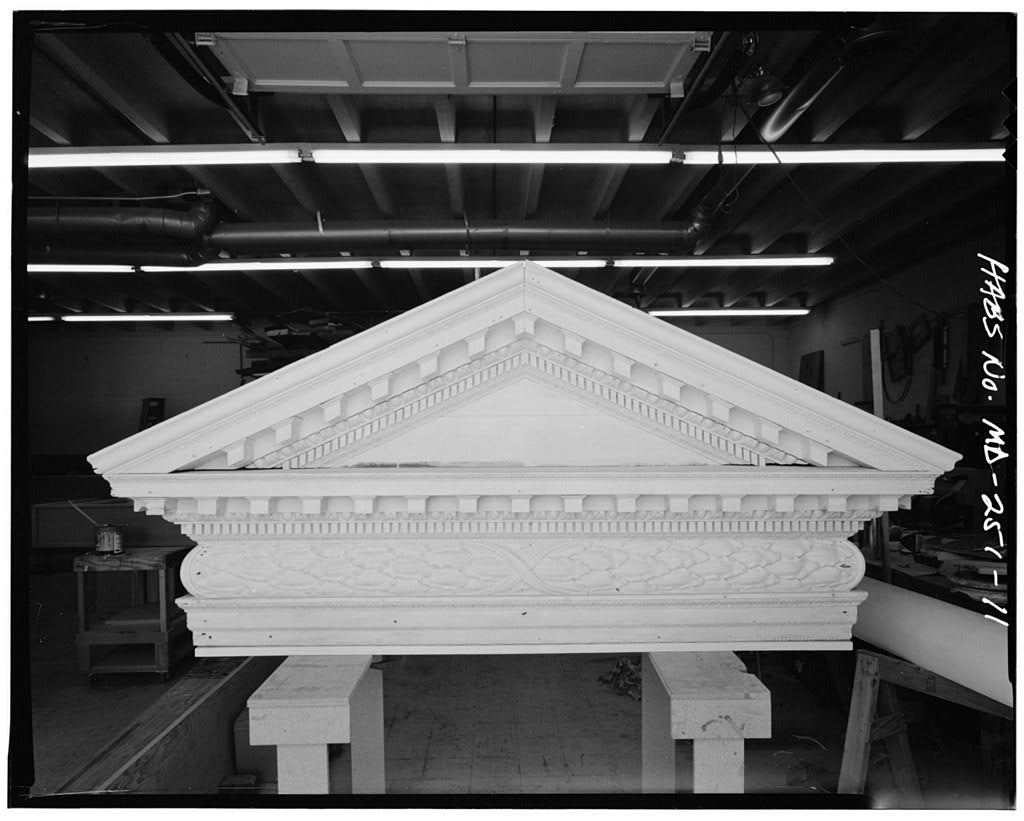

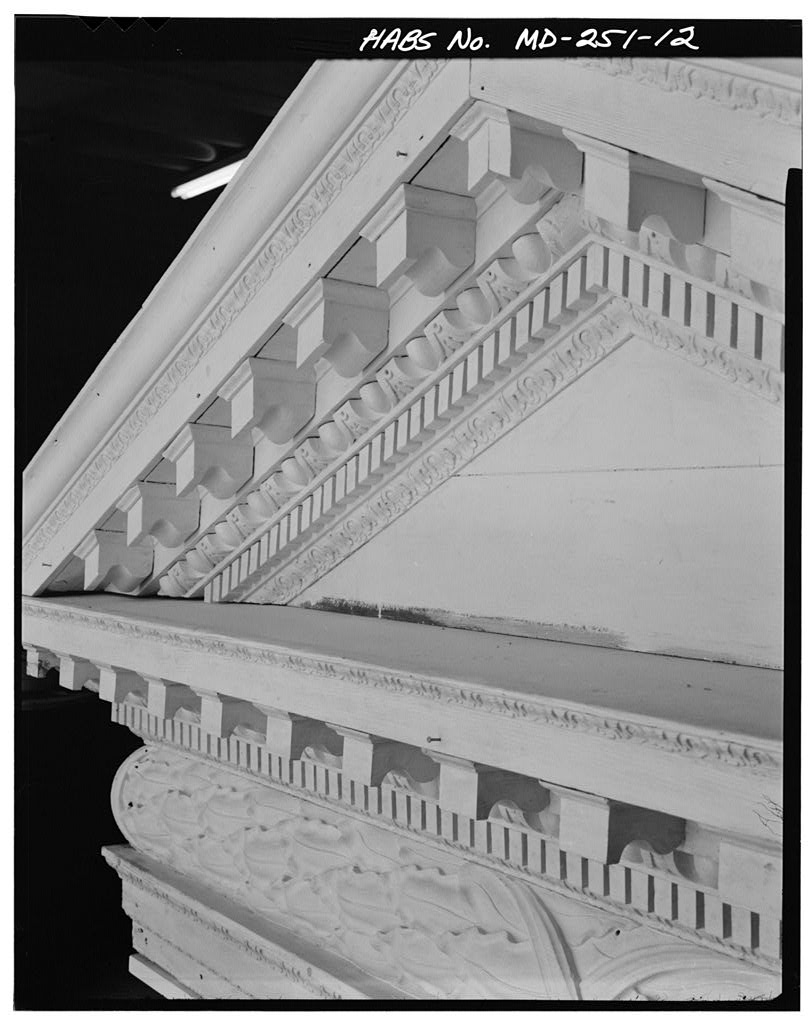

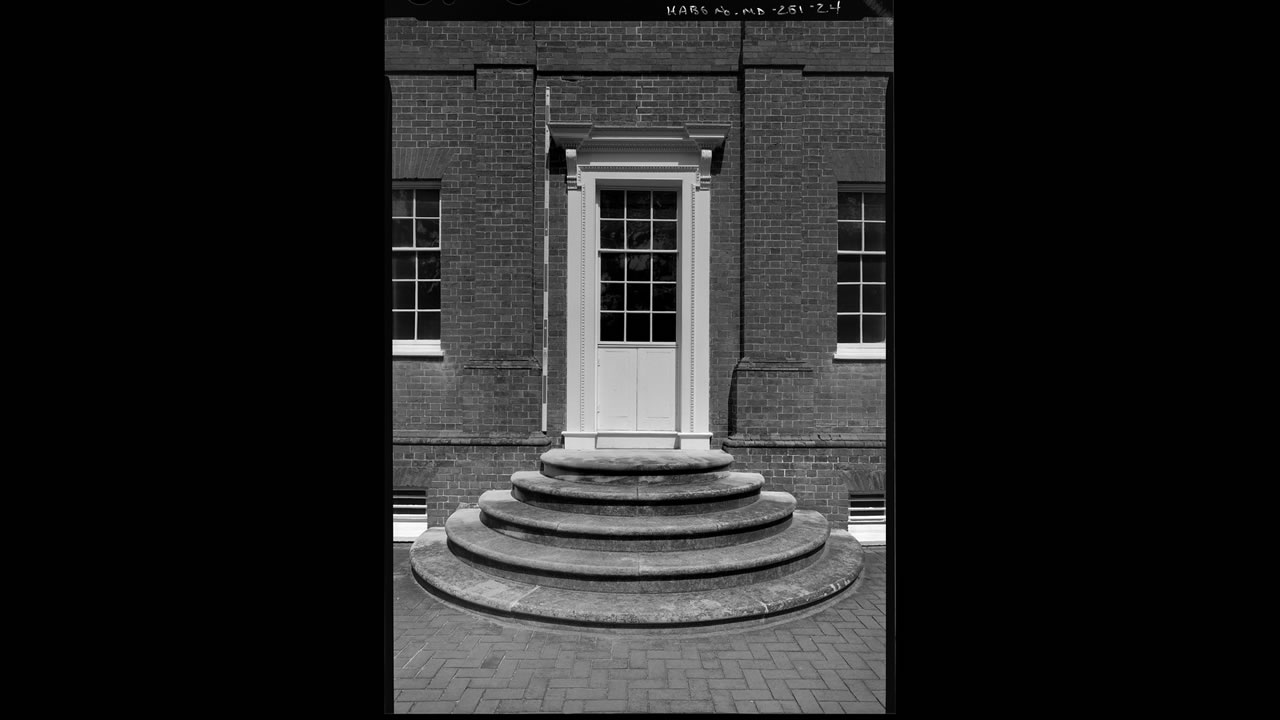

When the Hammond-Harwood House was included on the National Register of Historic Landmarks, the house's "richly carved doorway, set off against the plain brick wall,” was thought to be “one of the most admired in all of Georgian architecture."9

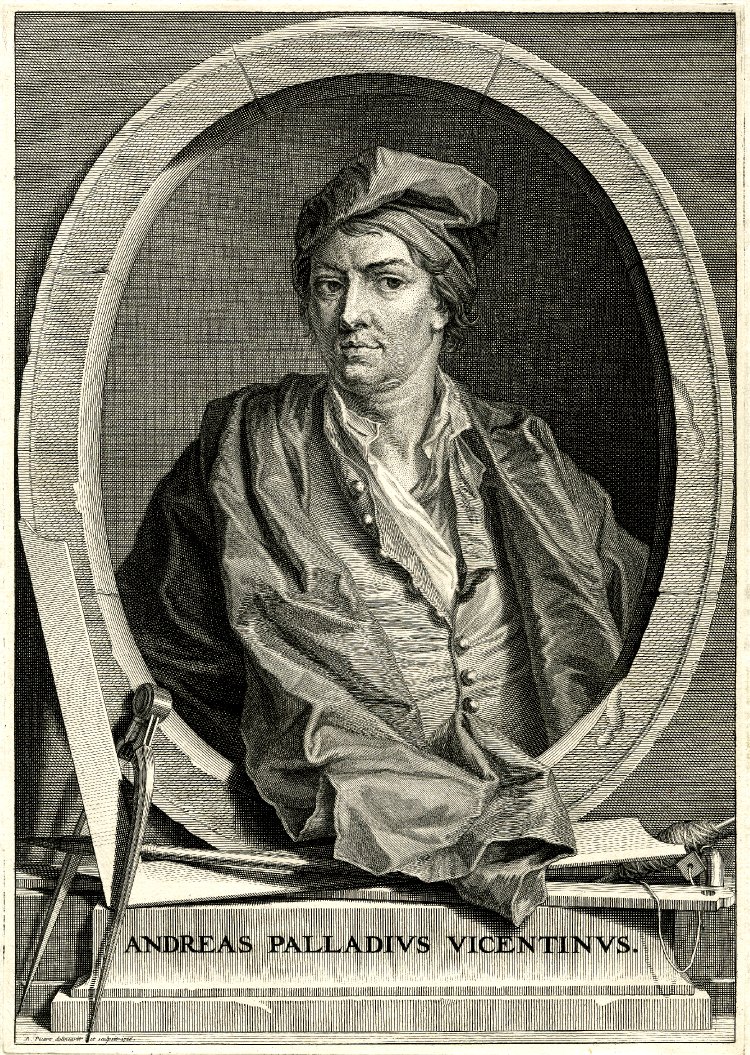

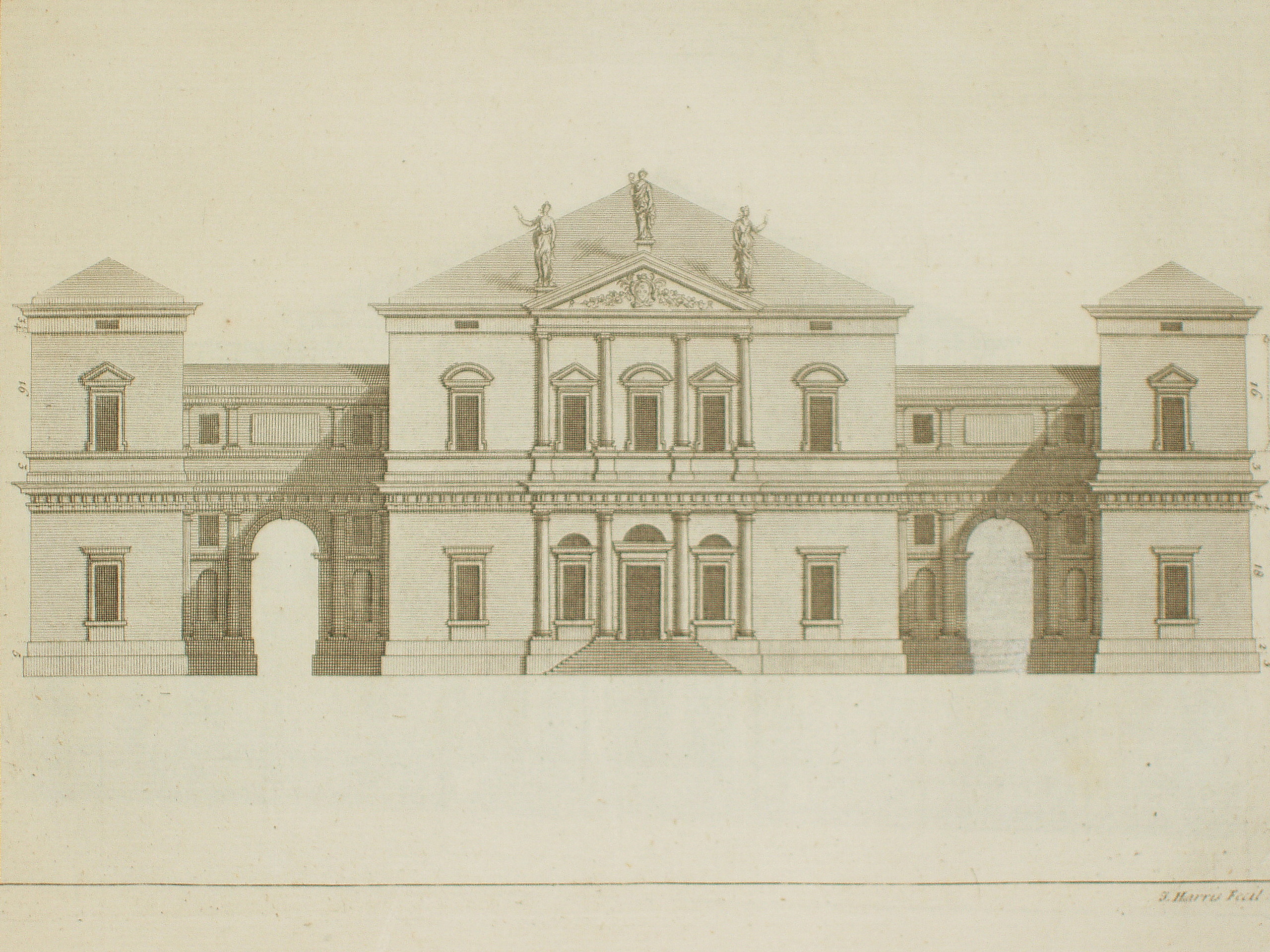

Andrea Palladio (1508 – 1580) was an Italian architect, his work is itself a revival of Classical Greek and Roman architecture, greatly influenced influenced by the work of Vitruvius. His architectural treatises Quattro Libri dell’Architettura providing easy models and formulae for adapting ancient architecture to modern life were published in 1570 to immediate success, both in Italy and abroad. They remain probably the most influential architectural treatise ever written.

The first examples Palladianism in the english speaking world are found in the works of Inigo Jones (1573 – 1652), who worked as an architect and designer under King Charles I and his wife Henrietta Maria. Under Charles I’s reign there was a radical change in the aesthetics of English taste towards a more Continental, and specifically Italian, taste. While engaged as The King’s Surveyor-General Inigo Jones built The Queen’s House at Greenwich, a simple and incredibly regular building whose proportional relationships reflect those of an open Italian loggia.This interest in proportion and its execution in The Queens House are deeply indebted to Palladio whom Jones met in Venice during a formative trip to Italy between 1598–1603.11

Left: Hardwick Hall East Elevation. John Dalkin, Photographer. Source. Right: The Queen’s House, Greenwich England. Christopher Harmer, photographer. rowleygallery.com

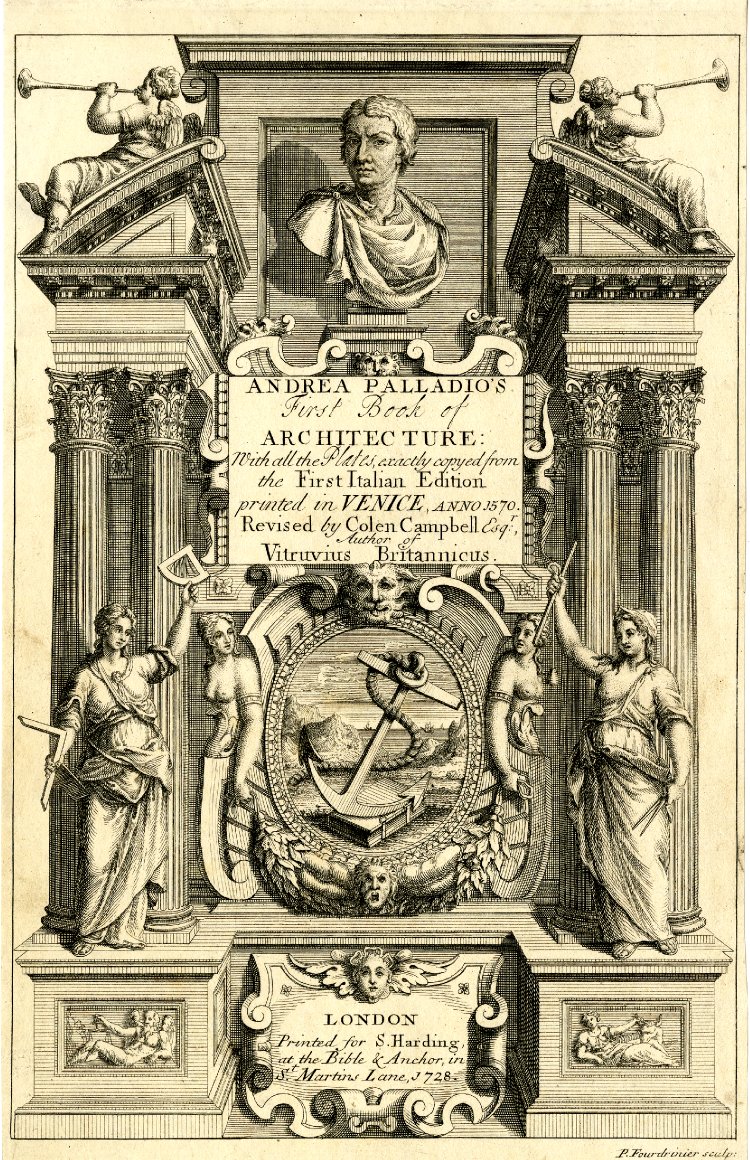

The classical Italian tastes of Charles I and Inigo Jones were interrupted by the English Civil War, which resulted in the beheading of the King and a general distancing from the tastes and frivolites of his court. After the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660 there was a great building boom and a return to interest in classical tastes and Italian architecture. In 1663 Godfrey Richards created a translation of the first book of Andrea Palladio’s four books of Architecture. This publication went into four more editions in the seventeenth century and at least six in the eighteenth century. Wittkower, in Palladio and English Palladianism claims that Richards text is likely a translation of Le Muet’s Traicté des cinq Ordres d’Architecture … traduit du Palladio12 instead of a direct translation. In Wittkower own words, “Thus, this little Palladio was in reality a hodge-podge of Italian, French and English material – and this sort of mixture is characteristic for English architectural books of the seventeenth century.”13 If English architectural books were of this mixed nature, we can conclude the majority of houses built based upon these manuals would also represent this mixed heritage.

A complete and corrected edition of Palladio’s works was not published in English until 1742. This text, the work of Giacomo Leoni, also contained a transcription of Inigo Jones’s own efforts at translating Palladio from over a century before.14 Leoni's version was well known in colonial America; copies by several translators and of various editions could be found in libraries in Boston, Salem, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston, as well as in the libraries of Harvard and Yale Universities. The inventory of the estate of the Virginia Carpenter Richard Brown lists a copy of Palladio as his only book. Thomas Jefferson, perhaps Palladio’s greatest advocate in America, called his book “the Bible,” and believed it should provide the basis for the new country's architecture. Jefferson owned seven editions of The Four Books during his lifetime.15

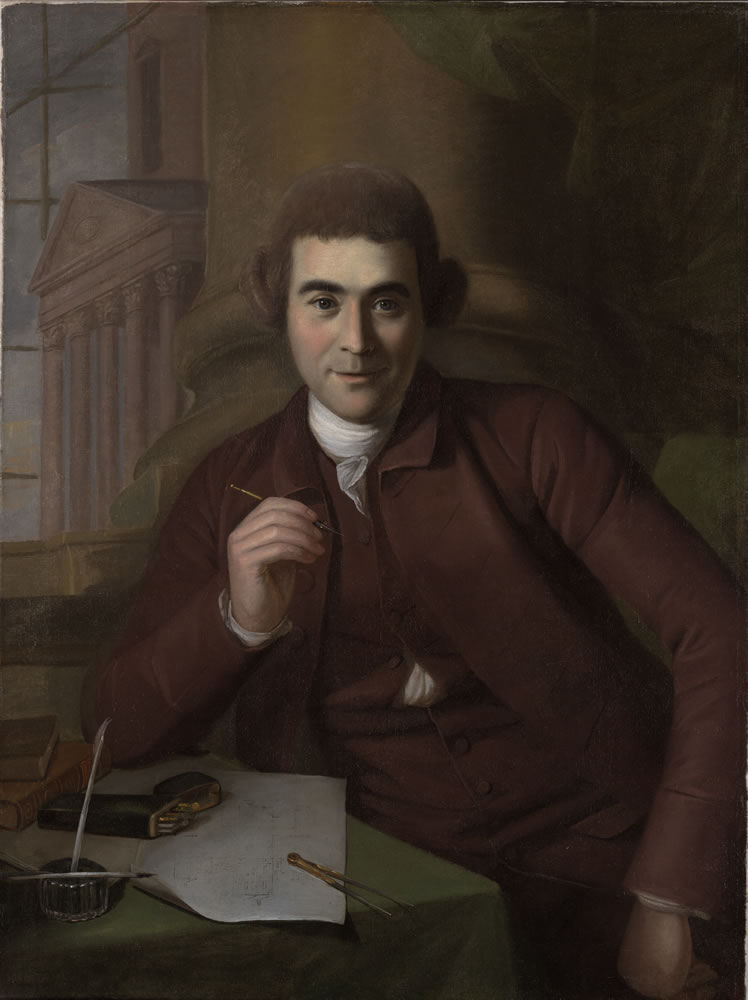

William Buckland, architect of the Hammond-Harwood house, was born in Oxford, England in 1734. At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed to his uncle in London to become a joiner. Joinery at this time was a craft distinct from carpentry and architecture, involving the creation of wooden framing and structural elements in a building. Buckland's apprenticeship, from April 5, 1748 to April 1755, coincided with one of the most dynamic periods of British furniture and architectural design. From 1720 to 1750, Palladian classicism dominated almost every aspect of design.16

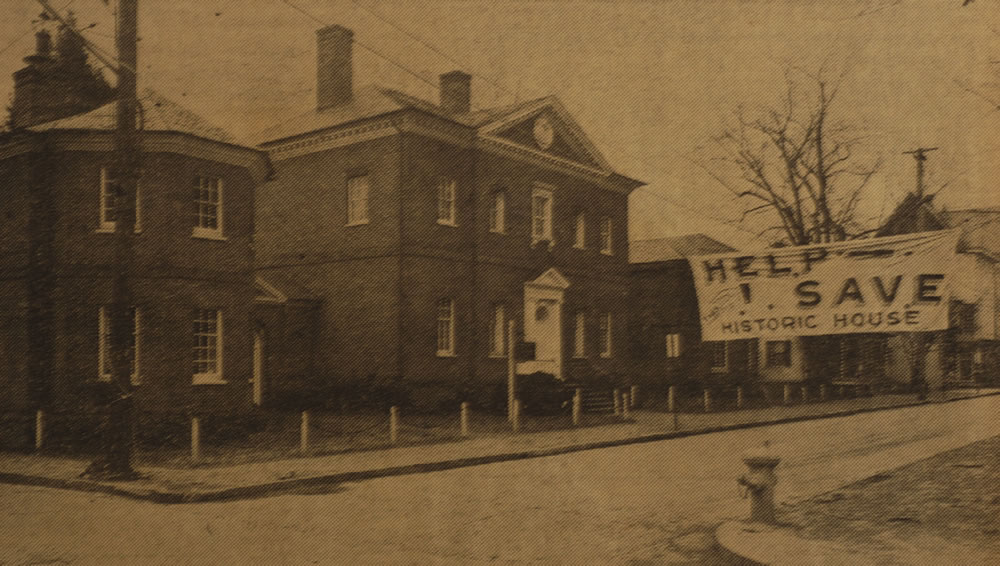

Although Matthias Hammond, who commissioned the house, is thought never to have inhabited it himself, the building remained a private residence until 1924. In the nineteenth century, the house belonged to the a family called Loockerman. William Buckland’s great-grandson, William Harwood married into that family. The name Harwood has been added to the name of the house in honor of the last private proprietress of the house, Hester Ann Harwood, Buckland’s great-great-granddaughter, who lived there until 1924.The current name thus reflects both the commissioner and the architect of the structure.

Many individuals recognized the architectural importance of the house. An article called “A Museum by Chance” in the April 1953 edition of Antiques relates the (possibly apocryphal) story of how the house came to be preserved. After Hester Ann Harwood’s death, the house was to be sold at auction. A woman named Mrs. Miles White, is said to have overheard a conversation at an antiques show in Newburyport, Massachusetts, about the intentions of Henry Ford to buy the Hammond-Harwood House and move it to Dearborn, Michigan. Mrs. White knew that administrators at St. Johns College had been inspired by the historic preservation efforts of Williamsburg, and that there was a popular regional belief that Annapolis had more and better examples of Georgian architecture than any other city in the country.17 The Hammond-Harwood House as a striking piece of this architectural heritage was an important part of Maryland's claim to national identity and heritage. A trustee of St. John’s College, at Mrs. White's request and with the blessing of the President of the College, went all the way to Detroit to ask Mr. Ford to withdraw his interest in the house so that it would not be removed from its original setting in Maryland. The college then purchased the mansion, creating what they considered to be “one of the great historical and architectural shrines of the country.”18

The house was intended to be a museum and to support the history of decorative arts program at St. John’s, the first of its kind in the country. Unfortunately, due to financial difficulties the building was open only sporadically during the 1930s, and eventually the college became unable to support the venture. The house was sold again in 1940, this time to the newly formed Hammond-Harwood House Association.

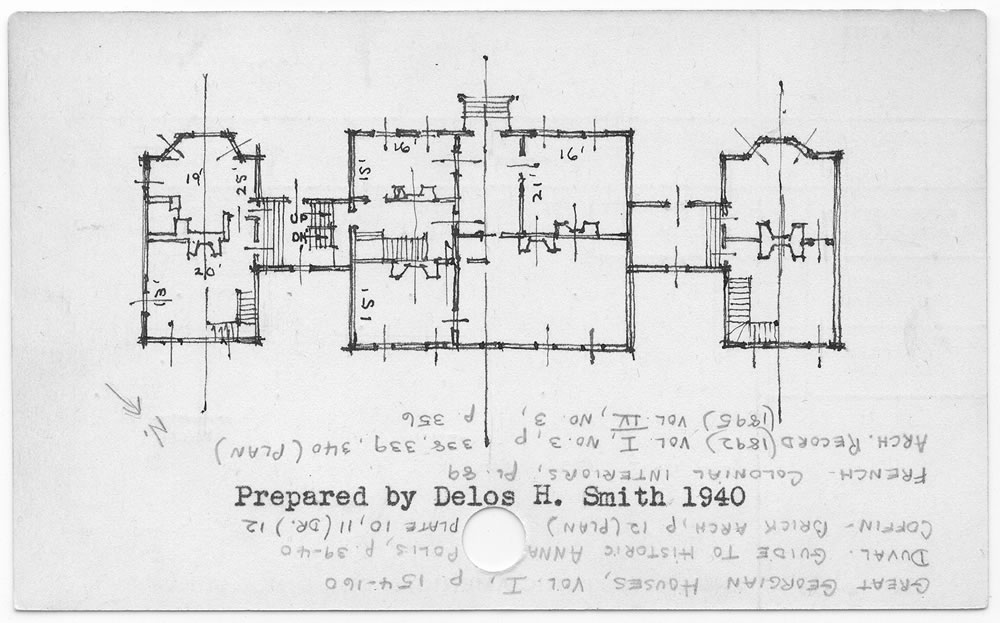

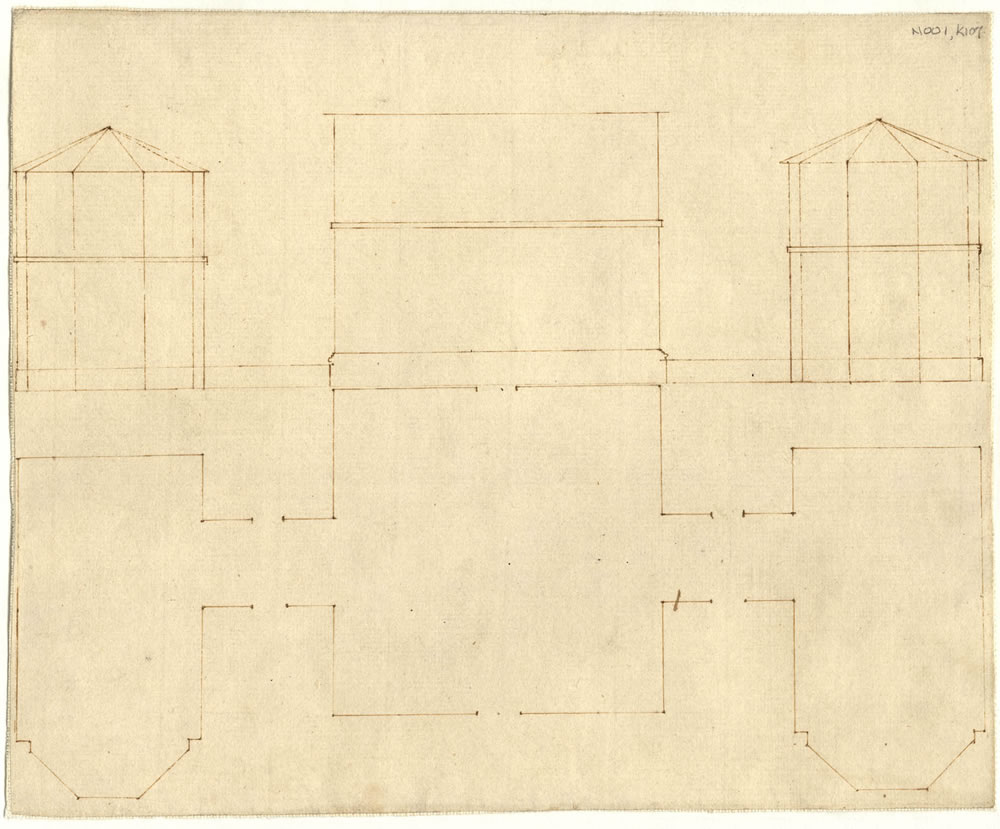

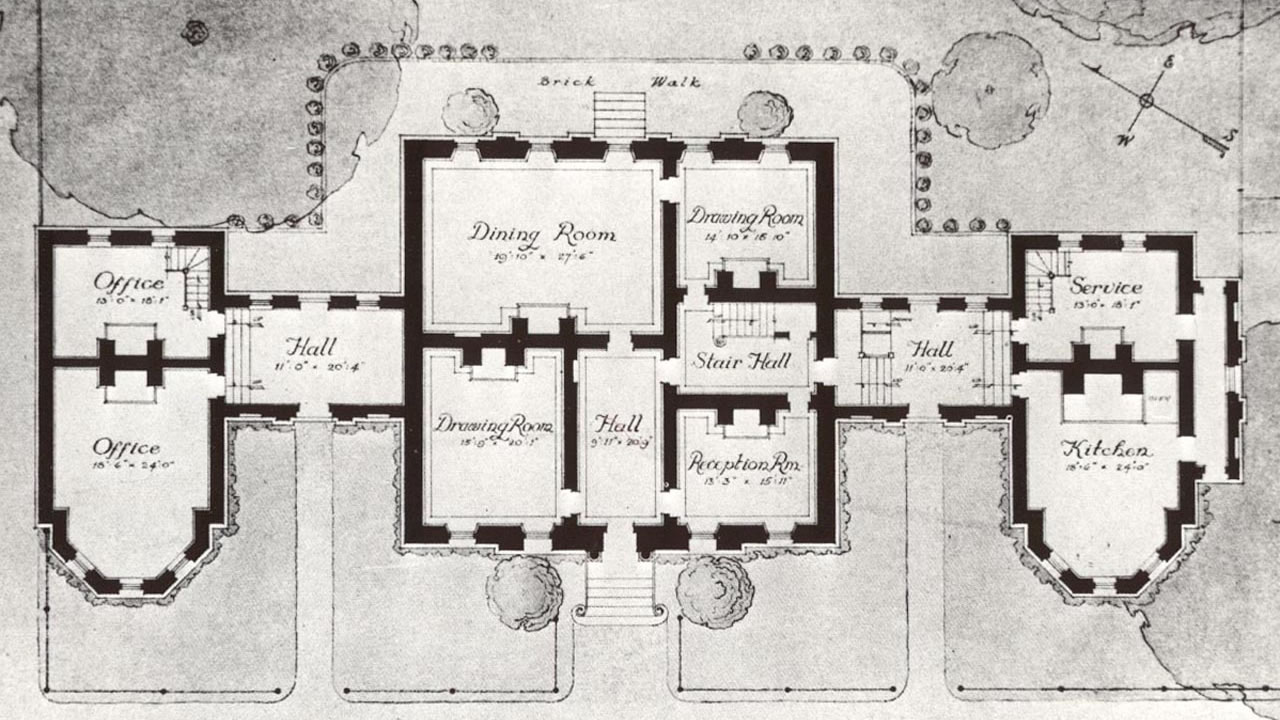

The Hammond-Harwood House, 22 Maryland Avenue, Annapolis, Maryland, is among the most significant Georgian residences of Colonial American. Important for the excellence of its design and refinement of detail, the building, completed in 1774, has the added distinction of being attributed with reasonable certainty to William Buckland, marking the period of his architectural maturity. The symmetrical brick building with a five-bay center section, is flanked by two-story end wings with polygonal bays. This last feature was extremely rare prior to the Revolution. The low- pitched, hipped roof and slightly projecting pedimented center is typical of the late Georgian period. While the exterior is less imposing than the three story Chase-Lloyd House across the street, its richly carved doorway, set off against the plain brick wall, is one of the most admired in all of Georgian architecture. All of these features combine to make this remarkable house a recognized colonial masterpiece.20

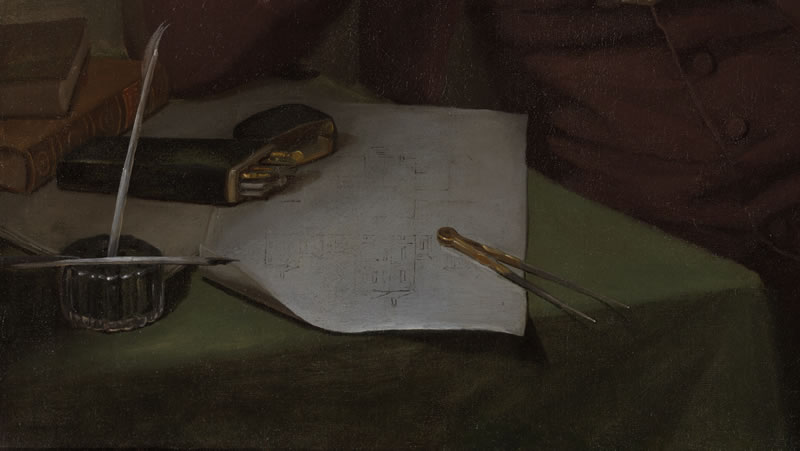

According to architectural James D. Kornwolf, only “one document, in the inventory of Buckland's estate, links Buckland both to the designs and its woodwork.”21 The house’s attribution to Buckland is based primarily on a portrait of the architect painted by Charles Willson Peale of the important Peale family of American painters. Correspondence relating to the furnishing of the Hammond-Harwood House in 1927 indicatex that the likeness was known to have been painted at the request of Matthias Hammond.22 It shows Buckland with a drawing bearing a plan and elevation of Hammond’s house and implicitly adds weight to the attribution. A portrait by Charles Willson Peale, who is best remembered for his depictions of heroes of the American Revolution, also implies that Buckland himself was an important figure.

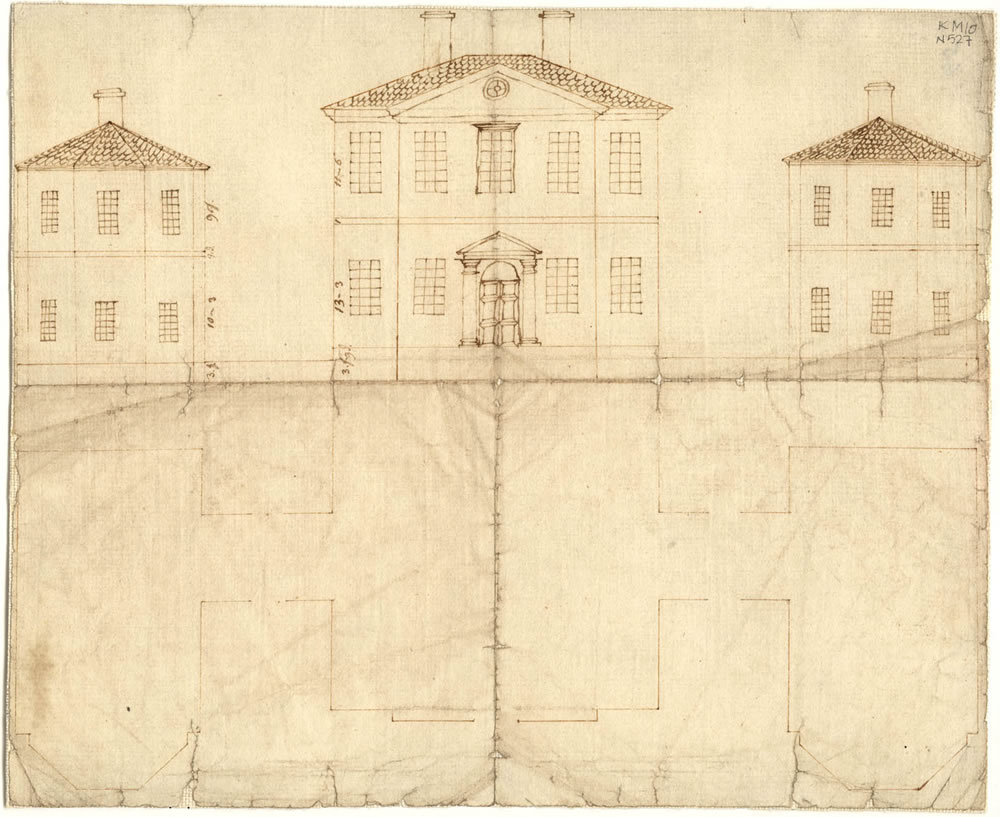

Interestingly enough, although the house was long-recognized as an exceptional example of “Georgian Architecture,” it was not until 2008 that Hammond-Harwood House Executive Director Carter C. Lively argued for the connection between its design and the Villa Pisani illustrated in plate 37, Book II of Andrea Palladio's 1507 Four Books of Architecture.25

Jefferson’s drawing suggests he recognized a Palladian design, especially since his home Monticello is the only other house known to have been designed directly from Palladio.26

Myth: History, Identity and Authenticity

“Truth ‘resides in myth—generalizing myths that direct social attention to what is common amid diversity by neglecting trivial difference of detail. Such myths make subsequent experience intelligible and can be acted on …. The simple fact is that communities live by myths, of necessity. For only by acting as if the world made sense can society persist and individuals survive.”27 – Michael Kammen

The restoration of Virginia's Colonial Williamsburg was a catalyst for historic preservation efforts during the 1930s. In the final years of Herbert Hoover’s administration, the federal government, through the National Park Service, increasingly supported in both restoration and preservation. This federal and eventual state involvement accelerated during the economic depression of the thirties, especially with the inauguration of the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1933.

Interest in the architectural forms of colonial America can be seen as simply an aesthetic choice, but this explanation underestimates the symbolic weight of those forms for the people who surrounded themselves with them. “When Frank Lloyd Wright held an exhibition of his work at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, he, being the publicist he was, could not refrain from decrying the restoration and its effect on current American architecture. Harold R. Shurtleff, who had worked on the restoration, replied to Wright: “it seems a pity that Mr. Wright’s so ready to deprive the man in the small or middle income bracket of confidence in such authentic source of dignity and beautiful forms for the sort of houses he can afford to live in as the Colonial Williamsburg restoration…. [I]t will be a long time before the materials and forms that were used in colonial architecture cease to have a place in American building.”29 Shurtleff’s response to Wright indicates the value he saw in the colonial.

“When Francis P. Garvan gave his magnificent ‘educational collection’ of early Americana (especially furniture and silver) to Yale University in 1930, he envisioned a museum setting because ‘all these good things are the gift of God, intended for all, not for a few.”32 Garvan also loaned parts of his collection to the Hammond-Harwood House, motivated by this same sentiment.

The Hammond-Harwood House has a reputation for an "authentic" look. Documents reveal that the building's interiors were in good condition when it was first converted from a private residence into a museum. Besides the furnishings collected by R.T.H. Halsey, the house maintained many objects owned by its early inhabitants. Over the years, the interpretation of the Hammond-Harwood house has changed little. Changing notions of authenticity often lead to a historic house's reinterpretation. Thinking about the authenticity of the Hammond-Harwood House in the context of Halbwach's idea that memory (and therefore history) is a constant revisionist process is then problematic. Is the house "authentic"—and has its interpretation always been so? Or is the interpretation flexible enough so as to seem constant as the needs of the public change and they adapt it for themselves, without the structure of the institution explicitly doing so.

Perhaps one can only know by entering the portal, and visiting that public space dedicated to sharing and exploring imagined common memories.

Tiffany Silver Tea and Coffee Service

An early colonial revival punch bowl by Eoff and Phyfe incorporates a neoclassical theme that has come to dominate the colonial revival style. More accurately described as neo-Neoclassicism, colonial revival objects were initially made as plain style alternatives to more elaborate Empire trends in the first half of the nineteenth century. Scholars have pointed out how fashionable clients sought newer trends while their more modest clientele purchased colonial style silver. It is helpful to understand the beginnings of the colonial revival as a continuation of Neoclassicism rather than a revival that appeared with a specific moment or idea. It certainly intensified in the centennial years, but colonial revival silver objects remained in production continuously from the middle of the nineteenth century to the present.

The design for the Tiffany Tea and Coffee service pictured above dates from c. 1898 and production of this particular style continued into the 1930s. It’s urn shaped silhouettes and finials identify an attempted Neoclassical reference, but early Federal Neoclassical silver looks markedly different (Met 33.120.525). Loose interpretations of colonial objects characterize many colonial revival tea sets of the early twentieth century. Though this might seem like a negative feature its important to remember that a lot of the iconic pieces of colonial silver that designers might have known were not yet institutionalized. The MFA Boston’s exhibition of early American silver was in 1906 and the Metropolitan displayed some pieces during and after the Hudson Fulton exhibition in 1909, but they did not acquire the Clearwater Collection until 1933.33 Like many other revival movements colonial revival silver did not need to be a copy in order to be understood. Motifs like Neoclassical urns and swags, faceted hollowware with bright-cut designs, eighteenth century style monograms, and pineapple finials could all be used as allusions to the colonial.

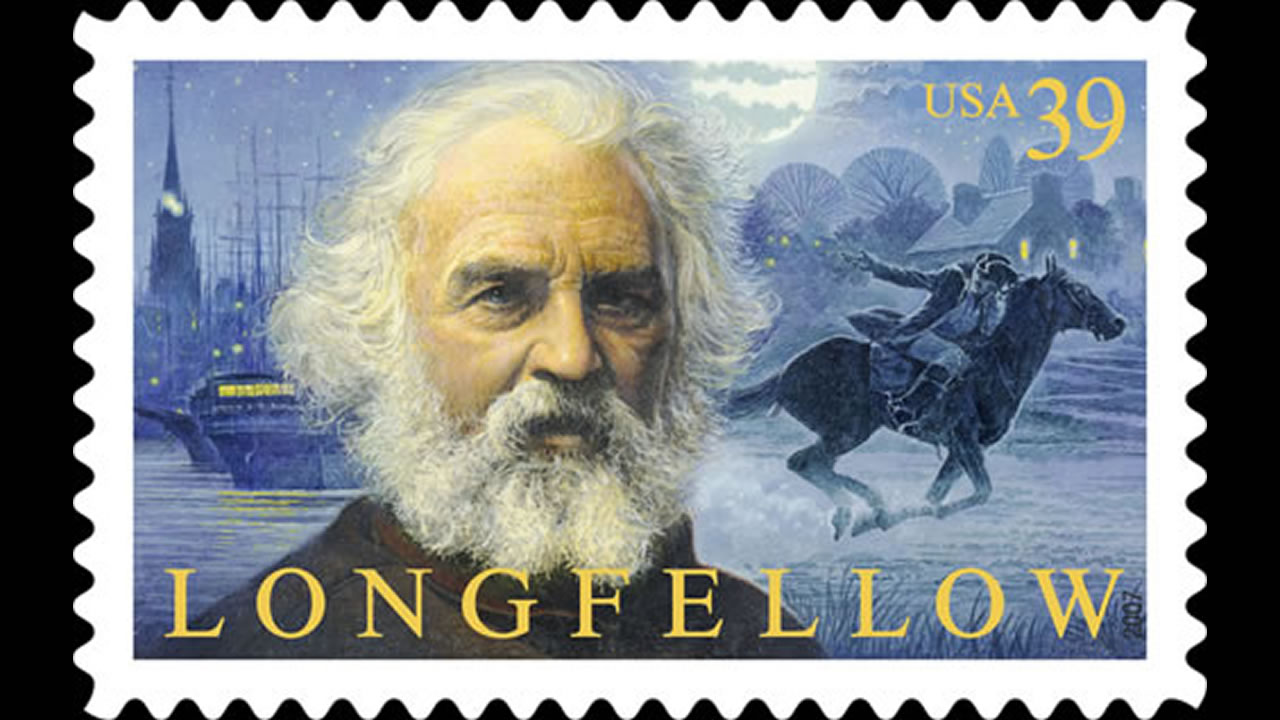

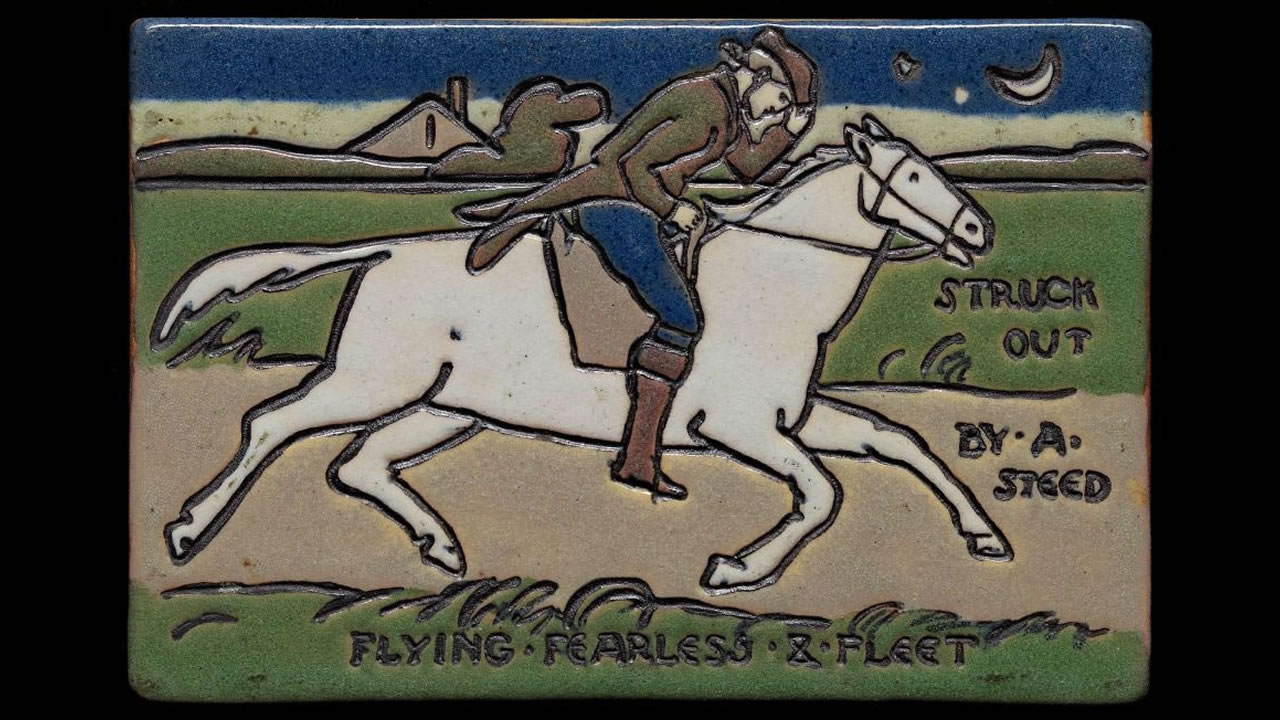

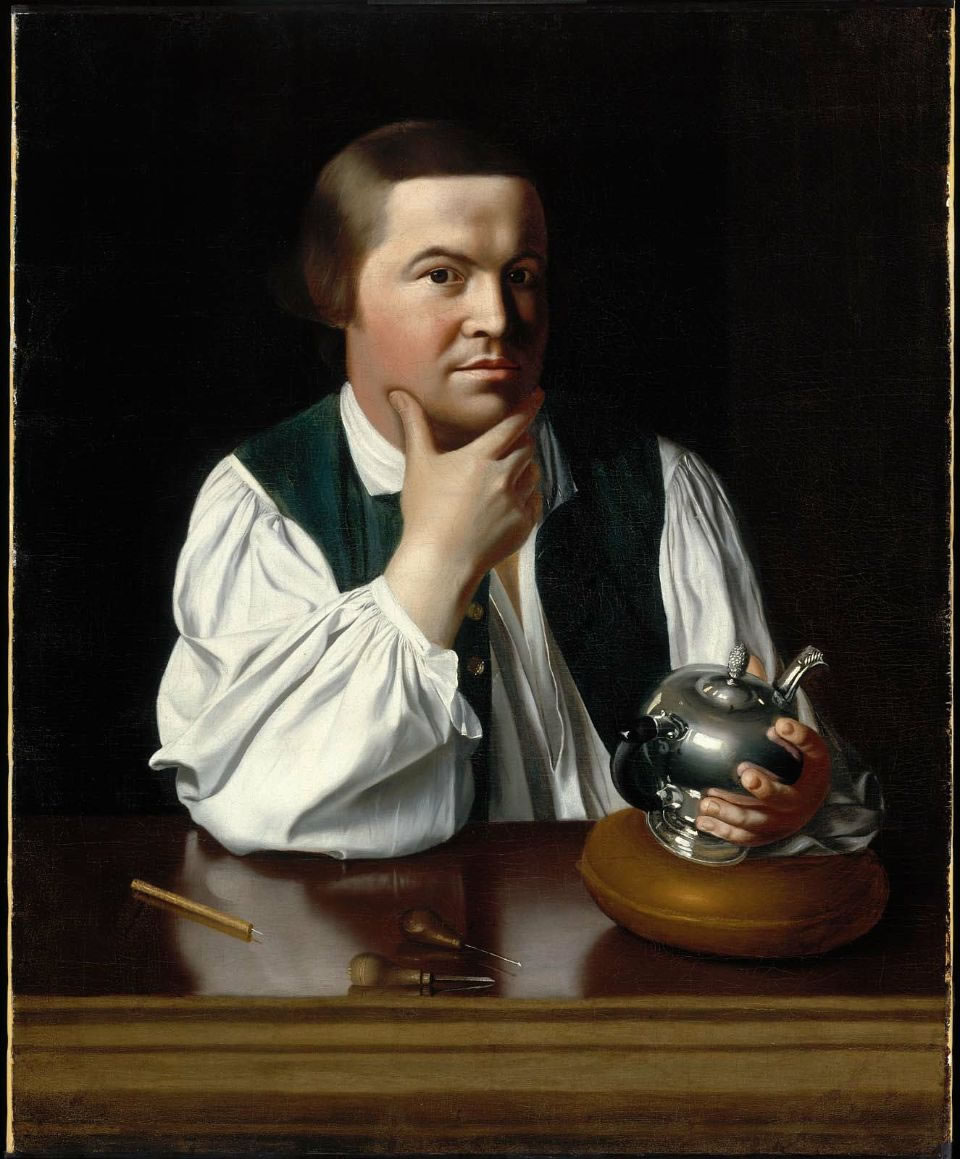

Most of the references are to the Federal or Neoclassical period of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Within this period, the most celebrated and well-represented colonial silversmith in museum collections was Paul Revere (1735-1818), and many of the shapes evoke Revere's aesthetic. See for example George Gebelein's Coffee and Tea Service of 1908. The sugar bowl alone might be a copy after a Revere original displayed at the MFA in 1906, but the rest of the set freely interprets what a Revere matched tea set would have looked like.34 John Singleton Copley's (1738-1815) famous portrait of the Boston silversmith embodies the myth created around Revere. A 1944 description of the painting reads,

As a strong indication of the pride in this craft, he had Copley paint his portrait not in the silk and ruffles of a prosperous merchant, but in the shirt sleeves and vest of his shop, a teapot in his hand with a few tools on the table in front of him looking as though he had just put them aside to show a customer the result of his order. There can be little doubt but that Copley showed him as he was—a somewhat burly, dark-haired, forthright fellow with rather compelling eyes and blunt features—a handsome craftsmen proud of his skill, not a dreamer, and by no means adverse to a bit of a fight if it should come his

way.35

Colonial revival silver strongly refers to Revere’s dual personality as a patriot and craftsmen. This ideology was picked up by American arts and crafts artists working at the same time Tiffany and others were producing colonial revival silver. In 1917, The Paul Revere Pottery of the Saturday Evening Girls Club issued tiles commemorating the Midnight Ride in an arts and crafts style. Many of the female potters were immigrants living in tenement housing in Boston’s historic North End. Learning and depicting the story of Paul Revere in their pottery was a way of becoming American. One interpretation of the colonial revival is that it could be used to reassert American national identity.37

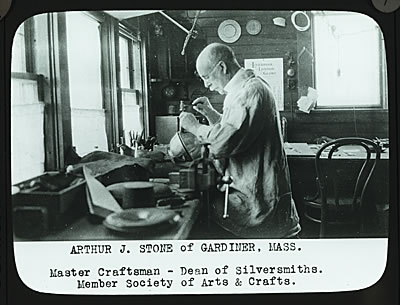

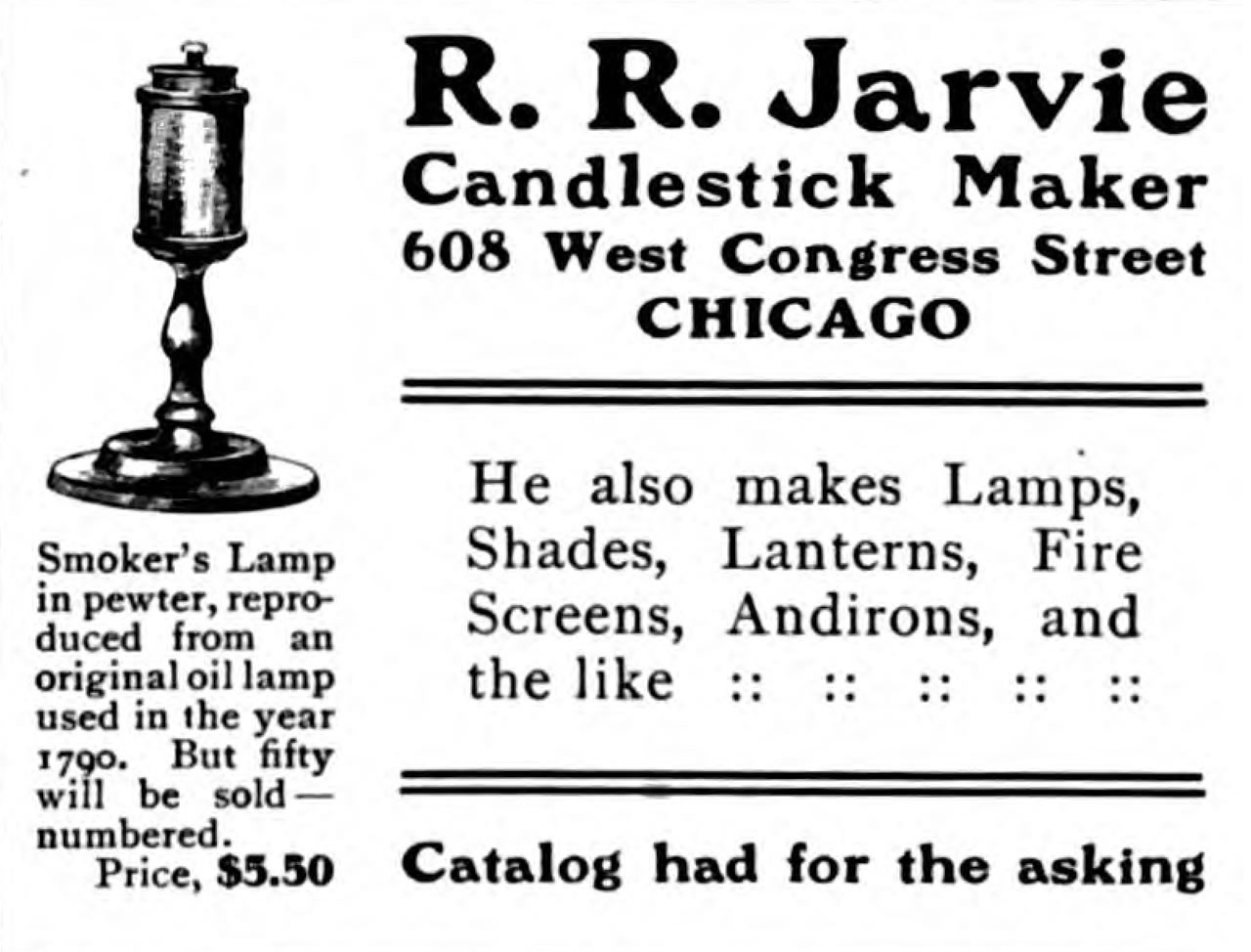

In contrast, Arts and crafts silversmiths were more attracted to Revere’s craftsmen status as depicted in the Copley portrait. Workshops run by George Christian Gebelein (1878-1945) and Arthur J. Stone (1847–1938) produced theoretically "hand-wrought" wares. These silversmiths promoted their products by associating themselves with arts and crafts ideals. In reality, Gebelein operated a large workshop that incorporated many employees and machine technology38 Stone, a member of the Society of Arts and Crafts, operated a workshop on the apprentice model just outside Boston. During his lifetime he was compared to Revere, which is unintentionally accurate. Both men oversaw other silversmiths and probably only finished more significant commissions. Robert Riddle Jarvie (1865-1941) more completely embraced the idea of the lone craftsmen raising silver from start to finish. He adapted Revere's designs for the modern home.39

This associational quality provides an interesting link between silver and folk. Paul Revere and Mary Chilton were folks, and one interpretation might suggest that colonial revival silver was part of a larger search for the “folk principle.”43 One manifestation of this is the inclusion of silver renderings after colonial teapots that are part of the Index of American Design. Silver as a medium resists folk because of its inherent monetary value and therefore elite status. However, as new technologies developed silver became cheaper and more people could afford an electroplated service. If real silver was still too expensive, metal companies were making chrome and stainless steel tea wares in a colonial revival style for the mass market.

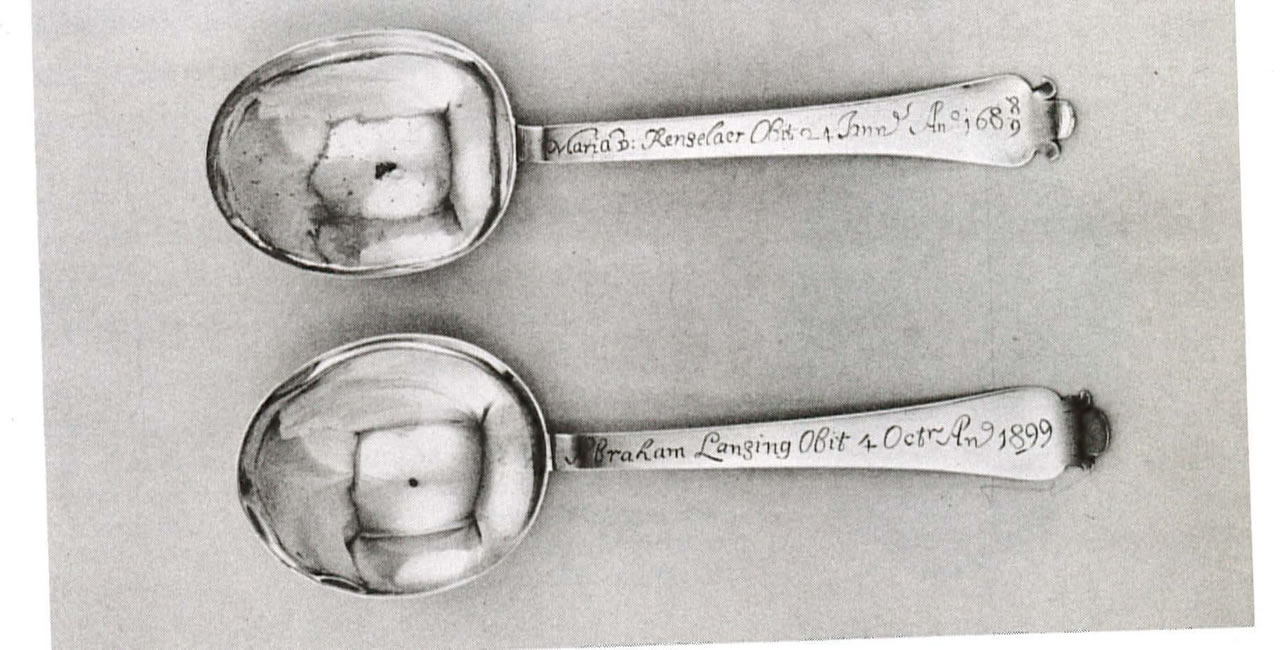

Patrons who were especially interested in literally associating themselves with colonial characters could also commission replica silver. One of the earliest examples of this practice occurred in Albany, New York. The Maria Van Rensselaer funeral spoon now at the Metropolitan Museum, was copied in 1899 for the funeral of her great-great-great-great granddaughter's husband, Abraham Lansing. Catherine Gansevoort, who commissioned the spoons for her husband, copied a model which was then still in her family. Not only did she replicate the form, but also the old Dutch New York tradition of giving spoons to pall bearers at funerals. 45

The centennial years also provided colonial enthusiasts an opportunity to recreate the past. A Tiffany inkstand stored in a time capsule safe re-emerged during the bicentennial, it was appropriately in a colonial revival style. Gorham made replicas of Paul Revere's Sons of Liberty bowl in a limited edition run of 500 (YC1976). These reproductions were far removed from questions of design ideals, and more appealing for their kitsch. 46 Traditional, conservative neoclassicism may have attracted the first generation of colonial enthusiasts, but in many ways kitsch can explain the continued appeal of these goods. Regardless of design elements, colonial revival signifies a style that will always have value.

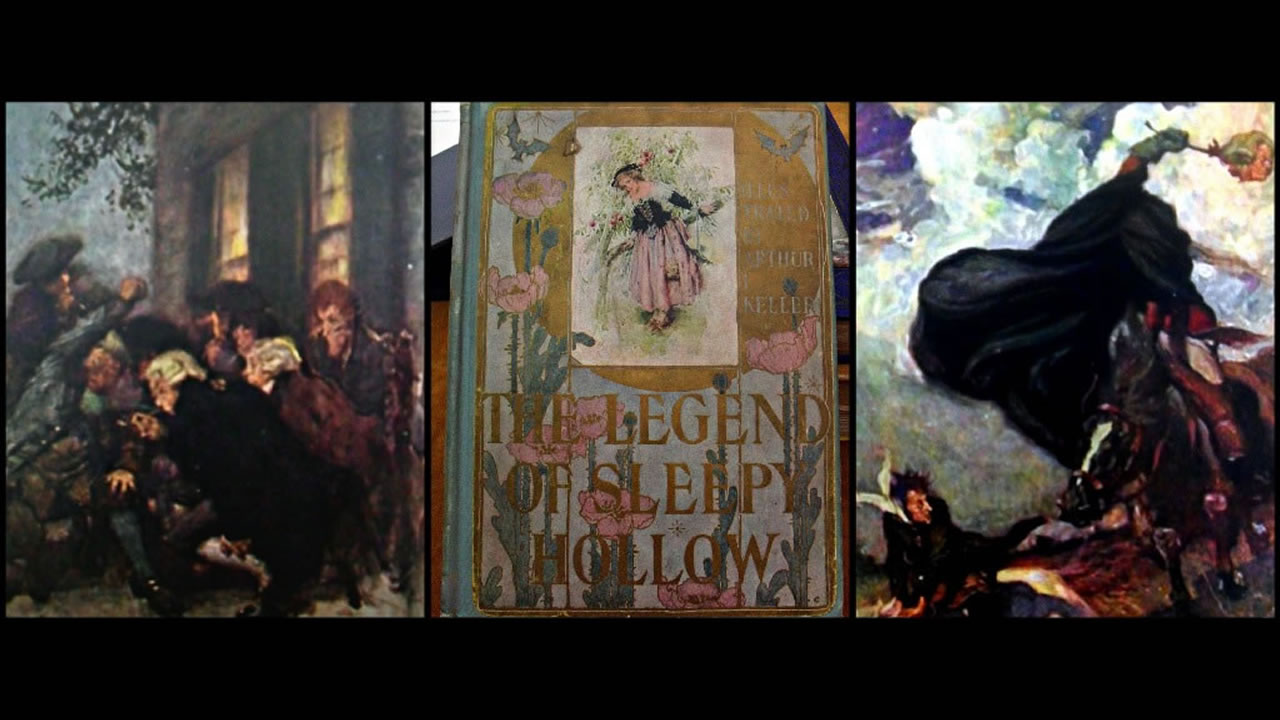

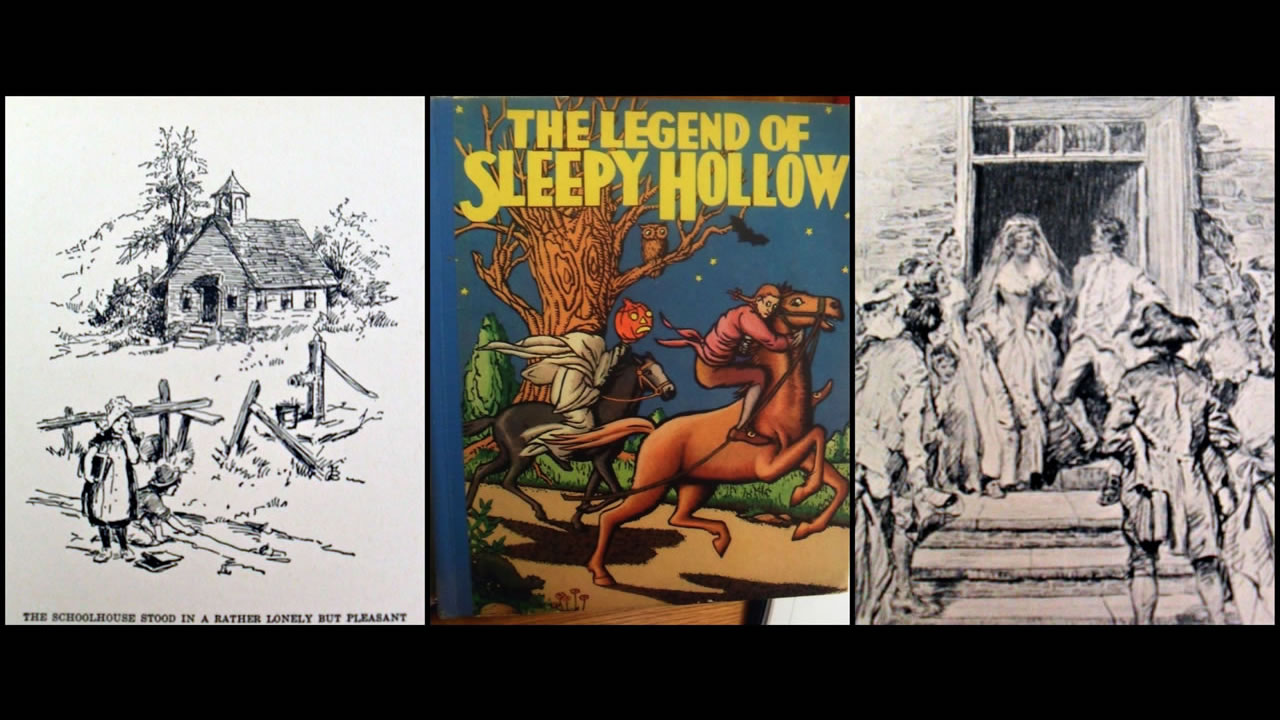

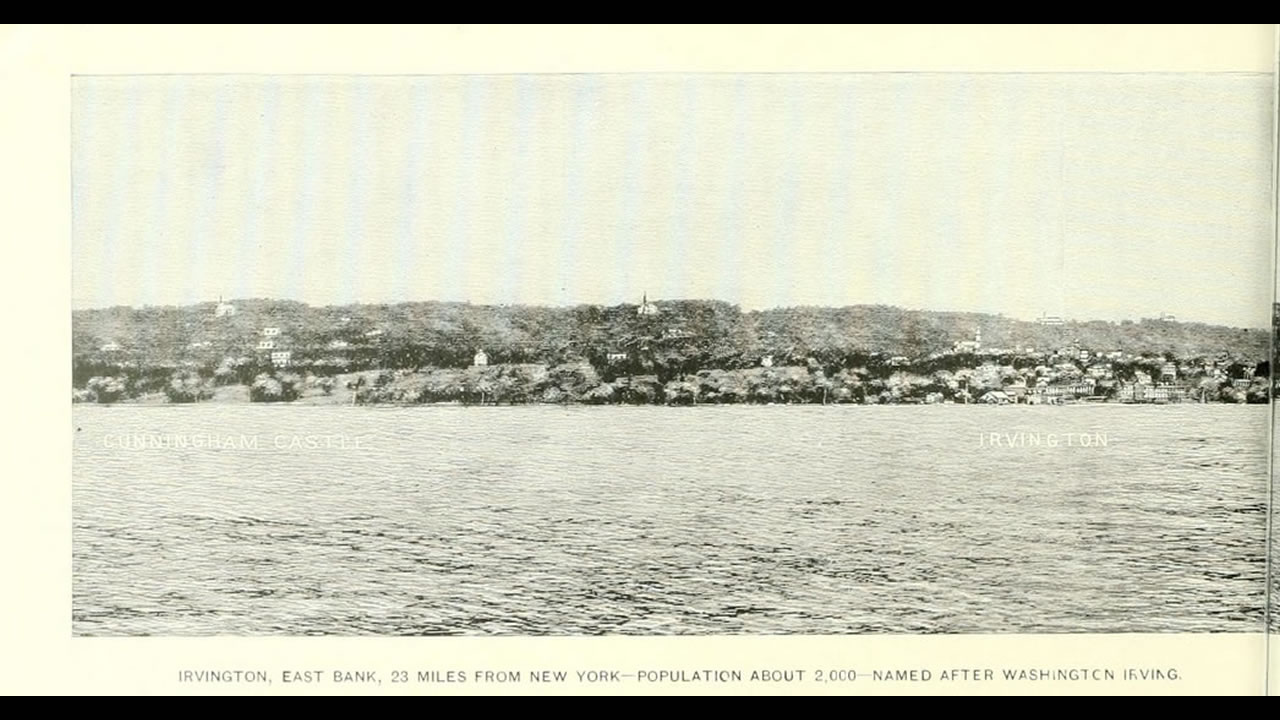

Sleepy Hollow

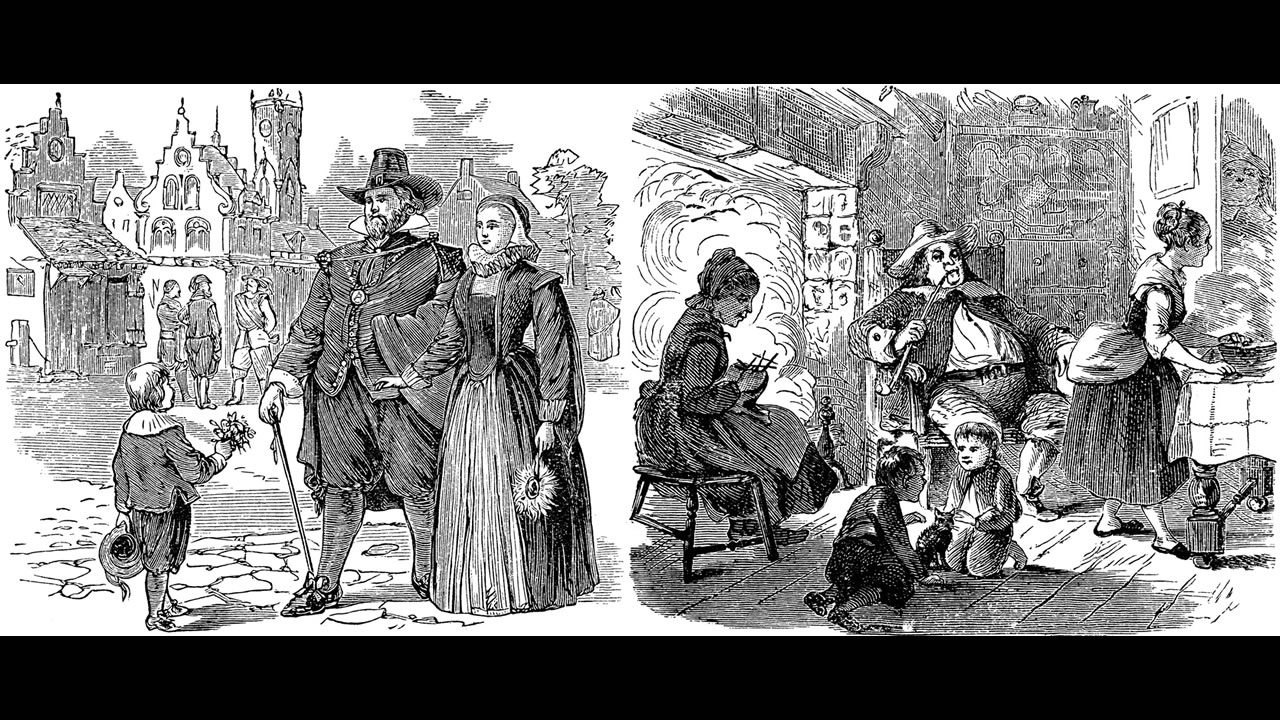

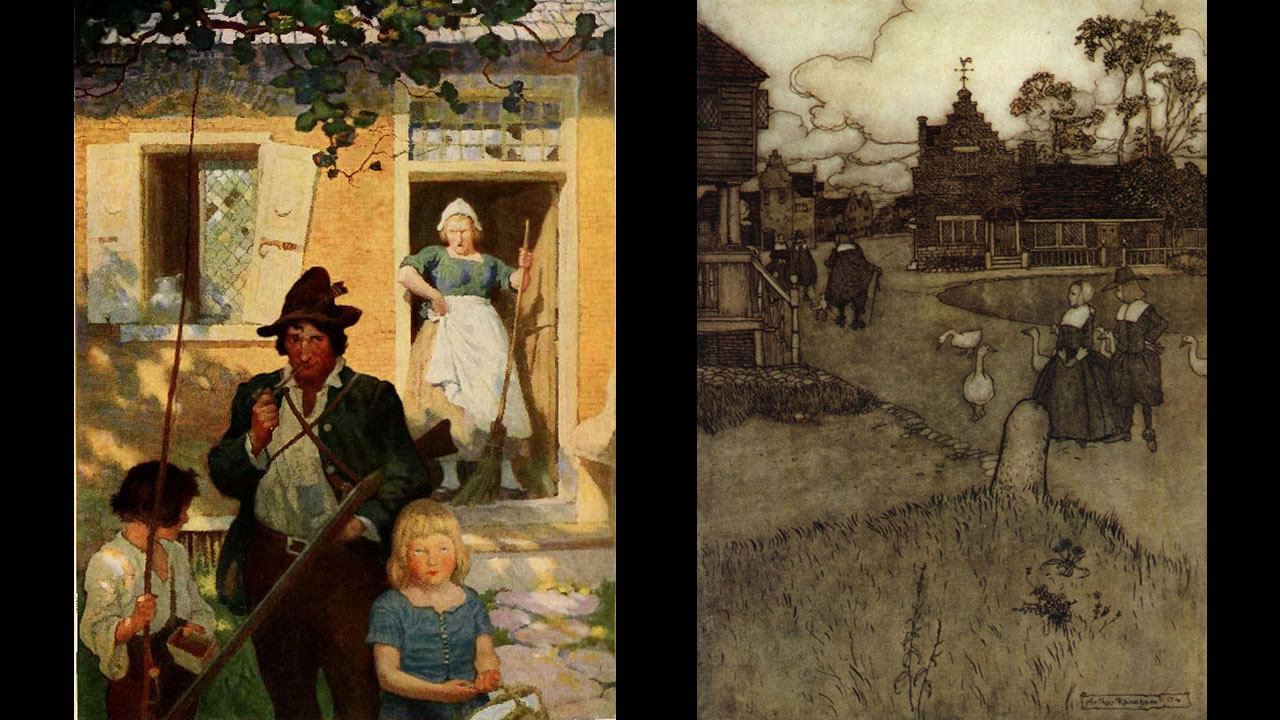

The legacy of Washington Irving's 1820 story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" can be found in its enduring themes of memory, history and longing for an idealized past.. The story is of Connecticut Yankee schoolmaster Ichabod Crane, who relocates to the small Dutch colonial hamlet of Tarry Town, New York. Impressed by its rural bounties, he becomes infatuated with the local beauty Katrina Van Tassel, which incurs the jealously of rival Brom Van Brunt. The county is haunted by a long-dead Hessian solider, who had lost his head in battle. At the climax of the short tale, the Headless Horseman chases Crane out of Tarry Town and Sleepy Hollow, and fades back into legend. The influence of "Sleepy Hollow" on nineteenth century audiences is evident in the popularization of Dutch colonial architecture, gothic imagery, regionalism, and a renewed focus on American history and tradition. Today, the story and themes remain familiar through visual culture, film, tourism, and historic preservation.

This project examines how "Sleepy Hollow" engages in multiple modes of artistic and cultural production, providing insight into how Irving's story operates as a key facet of the Colonial Revival.

Washington Irving: The Man, The Myth, The Legend

Childs & Jocelyn, Portrait of Diedrich Knickerbocker, from an Original Painting Lately Discovered by the Expedition of Holland, Frontispiece, 1894. Source: Washington Irving, Diedrich Knickerbocker's A History of New-York (Sleepy Hollow Press, 1981 reprint).

Washington Irving (1783-1859) grew up in Manhattan, but traveled widely throughout his life, visiting Europe and working as a diplomat, historian, and businessman. His primary career was as an author, writing dozens of tales of his boyhood home and adventures abroad. Irving's first major work was satire of the genre of local history. He assumed the name of Dutch ethnographer Deidrich Knickerbocker and wrote the aggrandizing A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty (1809). Despite the exaggerated nature of this story, the public took it quite seriously and the mysterious Deidrich Knickerbocker was much sought after, but never found.

In fact, Knickerbocker was a character in another of Irving's "histories" of America, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon (1819-1820). This series of short pieces was published in New York to enormous popularity, including the story "Rip Van Winkle" and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow." Irving described the latter as "a Knickerbocker story which may please from its representation of American scenes. It is a random thing, suggested by recollections of scenes and stories about Tarrytown. The story is a mere whimsical band to connect descriptions of scenery, customs, manners, etc."47

In his characteristic style, Irving built a chain of fictitious narrators within the story: Geoffrey Crayon, the pseudonym Irving uses for the Sketch Books, announces that he found the tale of "Sleepy Hollow" within the notes of Diedrich Knickerbocker, a pseudo-ethnographer of Dutch traditions, who himself had heard it at a club in New York from a man who claimed the story was told to him by a Tarry Town farmer. The question of the authorship and 'authenticity' of the story is open to interpretation by the reader, mirroring how Irving himself viewed the malleable, and in certain ways fictitious, narratives of American history.

Gender, Culture and Capital in Irving's Nineteenth Century America

Before earning a living through his pen, Washington Irving experienced little success as a speculator, having gone into bankruptcy whilst working with his brother in England. His monetary woes prompted his return to writing, which proved to be a more fruitful endeavor as his works enjoyed both commercial and critical success. However, when he returned to America in 1832, Irving found New York City much changed, and not, in his opinion, for the better. The Dutch Manhattan of his boyhood was now filled with opportunistic Yankees who had destroyed many of the city's historic landmarks. The feeling of disorientation Irving felt resulted in his mission to restore to America the community values that he believed were being lost. His stories idealized the insular, domestic villages of the countryside, in contrast to the encroaching threat of urbanism and industry. 48

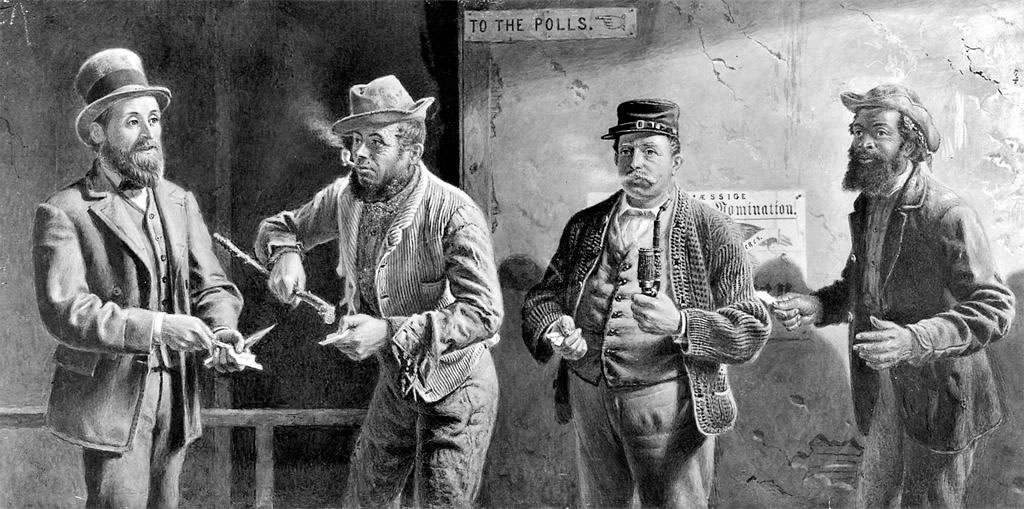

The figure of the Yankee, embodied by Ichabod Crane in "Sleepy Hollow" was tied to capitalism in the early nineteenth century, as a cash—based economy began to supplant the existing landed wealth that folks such as the fictional Baltus Van Tassel held dear. Crane, when looking upon the land, only sees the opportunities to have it parceled out, dreaming of how it might be “readily turned into cash and the money invested in tracts of wild land.” 48

His hunger for this property is mirrored by his voracious appetite for food and ghost stories. Irving focused on Crane’s yearning as an allegory for the greed and gluttony of Yankees, restless to consume all that was around them. While Washington Irving was himself cash-poor but rich in cultural capital, he identified in the Yankee "type" a real and present economic danger to the domestic landscape of Tarrytown; more of a threat, in fact, than the Headless Horseman.

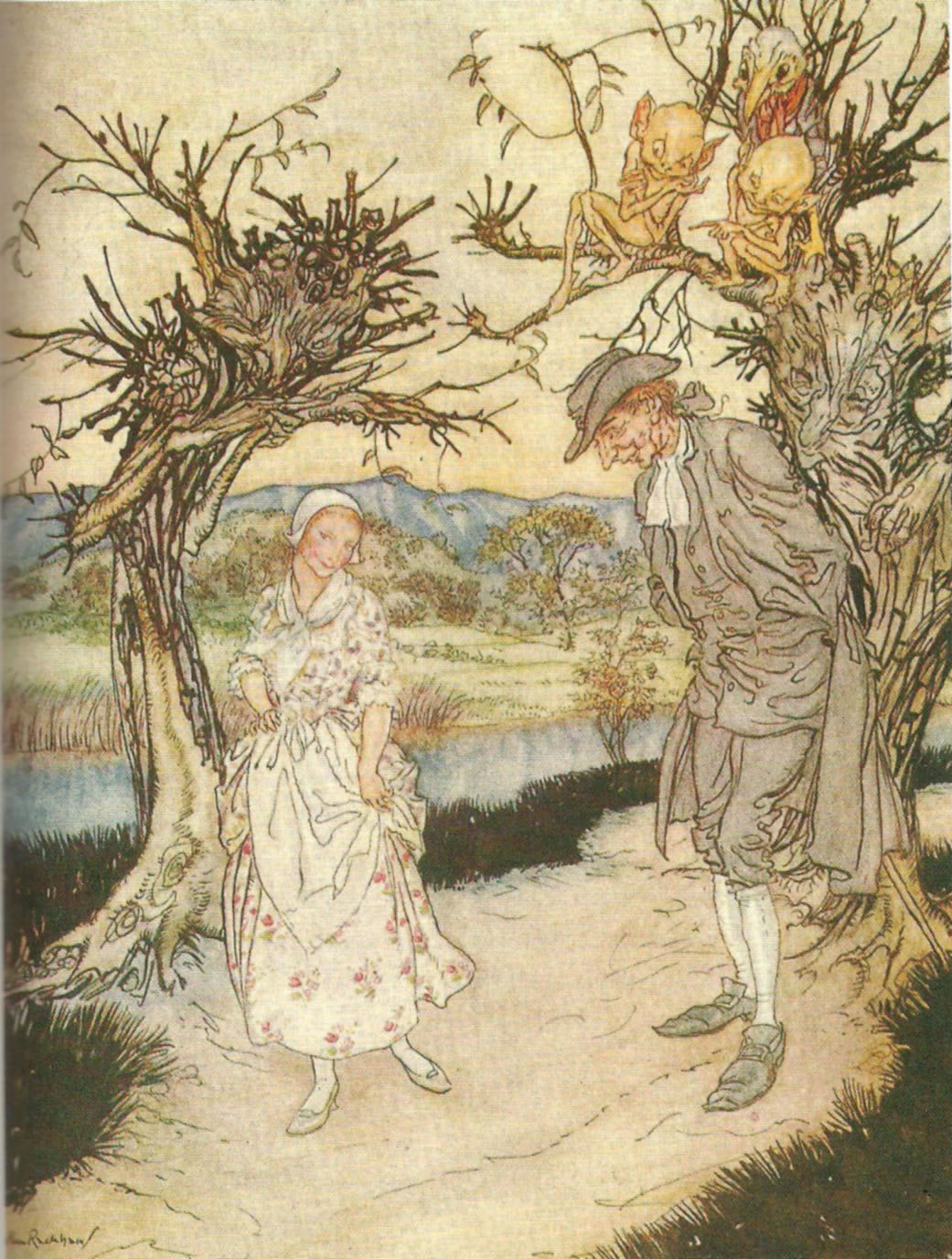

Arthur Rackman, Illustration from "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," 1905. Source: Peter Harrington Rare Books.

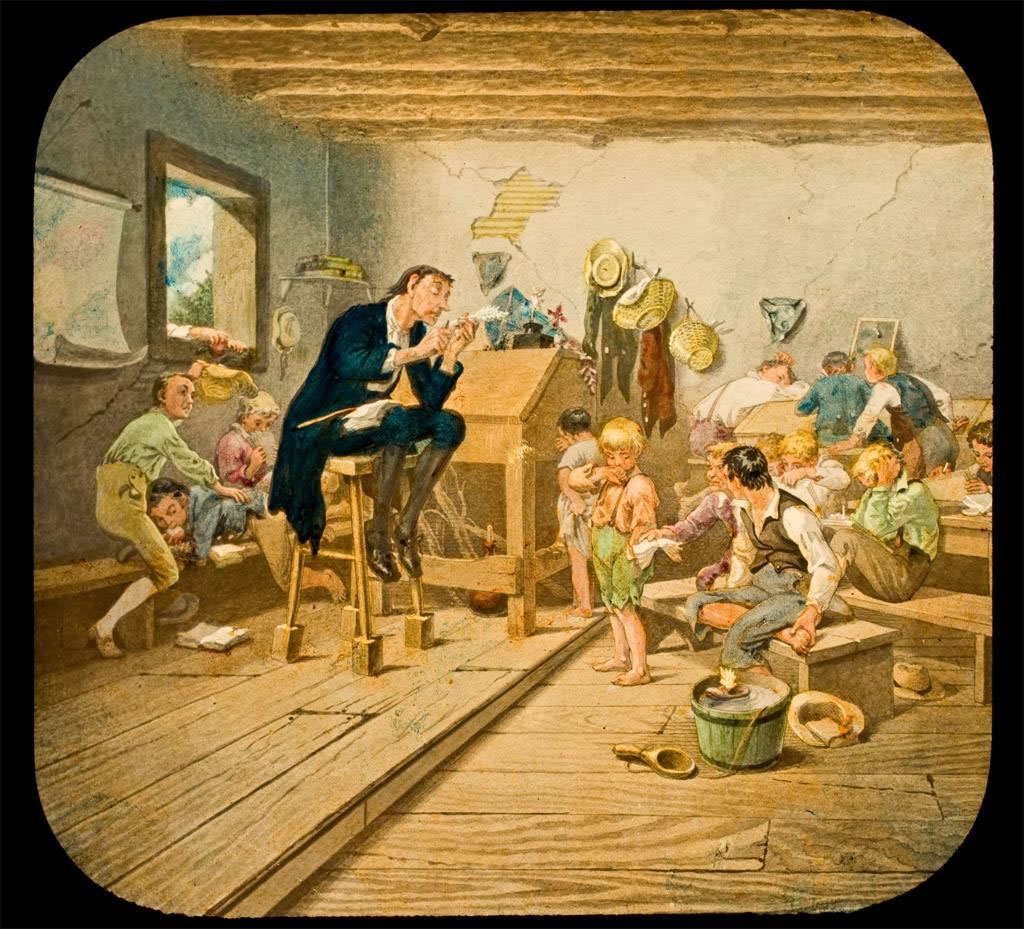

Perhaps less transparent in Irving’s story were the complex anxieties over gender, as erudite and cerebral Crane was pitted against the robust farmer Brom Von Brunt, for the hand of Katrina Von Tassel. Described as, "foremost at all races and cock fights; and, with the ascendancy which bodily strength always acquires in rustic life," Brom is Crane's physical and intellectual antithesis.50 By contrasting these two different kinds of men, and their associated capital, Irving keyed in on the insecurities of men like Crane, who were "implicated in an influenced by the vicissitudes" of the market. As capitalism became a more dominant economic force, so too did the conception of selfhood shift towards valuing the individual over, or even against, the community. Within the quiet and content Sleepy Hollow, Ichabod Crane carries nothing but his education and intellect, making him an amusing and rather self-important figure to the townsfolk. Irving even described Ichabod Crane as a series of caricatured features. “Tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, and his whole frame most loosely hung together. His head was small, and flat at the top, with huge ears, large green glassy eyes, and a long snipe nose, so that it looked like a weathercock, perched upon his spindle neck…one might have mistaken him for the genius of famine descending upon the earth, or some scarecrow eloped from a cornfield.”51

C.W. Briggs Company, Ichabod Crane, the Village Schoolmaster, transparency, collodion on glass with applied color, 3 1/4 X 4 in, 1981. George Eastman House Still Photograph Archive.

Dutch New York vs. New England

In his constructions of "Sleepy Hollow" and the Dutch communities in "Rip Van Winkle," Irving plotted differences between a pre- and post-Revolutionary society that could inform, rather than alienate, each other. He attempted to instill cultural familiarity with the colonial Dutch by emphasizing their vernacular architecture, rural traditions and social structure. By returning to the ideals they modeled, in an increasingly restless post-Revolutionary society, Irving hoped to link their legacy with America’s own development as a nation in need of a historic anchor.

The Dutch were not without their critics in the early nineteenth century. Anglo-Americans viewed them as clannish, insular and backwoods, standing in the way of progress. As explained by historian Joseph Manga in Anette Stott’s Holland Mania, “Instead of the expected model of republicanism, the Netherlands became a byword for all shortcomings of federalism that the American Constitution was intended to avoid. Immigrants of Dutch stock, too, were often displayed as representatives of outmoded traditions with modern citizenship.”52

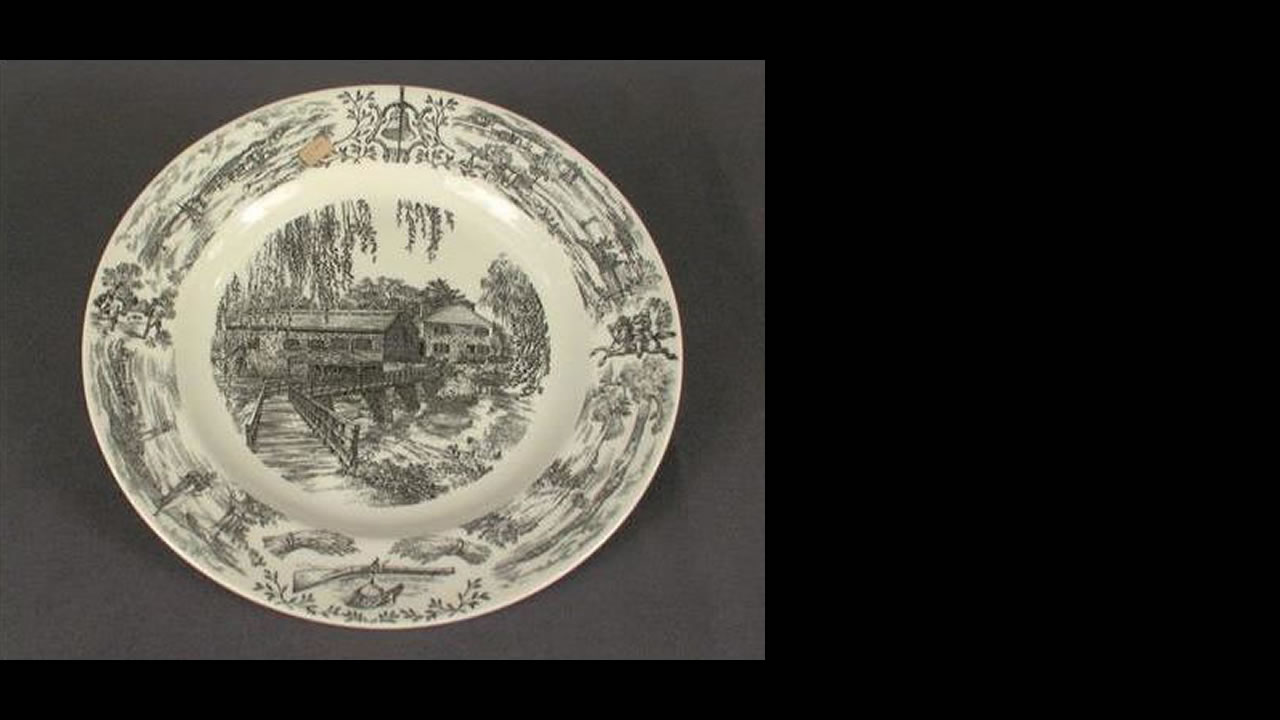

Irving himself acknowledged this critique, particularly as he used his earlier Knickerbocker History to parody the regional pride inherent in the Dutch townships, to the dismay of his readers. However, sentiment toward the Dutch changed rapidly towards the turn of the twentieth century, and Irving is credited with popularizing what became "Holland Mania," a movement that located in the Dutch a more 'authentic' American historic legacy. Editor Edward Bok, in a 1903 article in The Ladies' Home Journal, made the proclamation that Holland was the true mother country of the United States, and that Americans should look to the Dutch for an assertion of their own national character. This cultural re-write had its roots in an Irving-esque historical longing for tradition and stolidness in the face of a rapidly diversifying population and a more complex industrial landscape. "Sleepy Hollow" and "Rip Van Winkle" foreshadowed this movement, as Holland Mania represented “A romantic, historicized and somewhat stagnant Holland…a blissful counterpoint to the grim realities of modernity.” 53 The Dutch embedded themselves in popular culture, realized through developing tourism in the Hudson Valley, the proliferation of artwork adapting Irving's tales, and the historic preservation of Dutch colonial architecture, which Irving himself spearheaded with his restoration of Sunnyside in 1835.

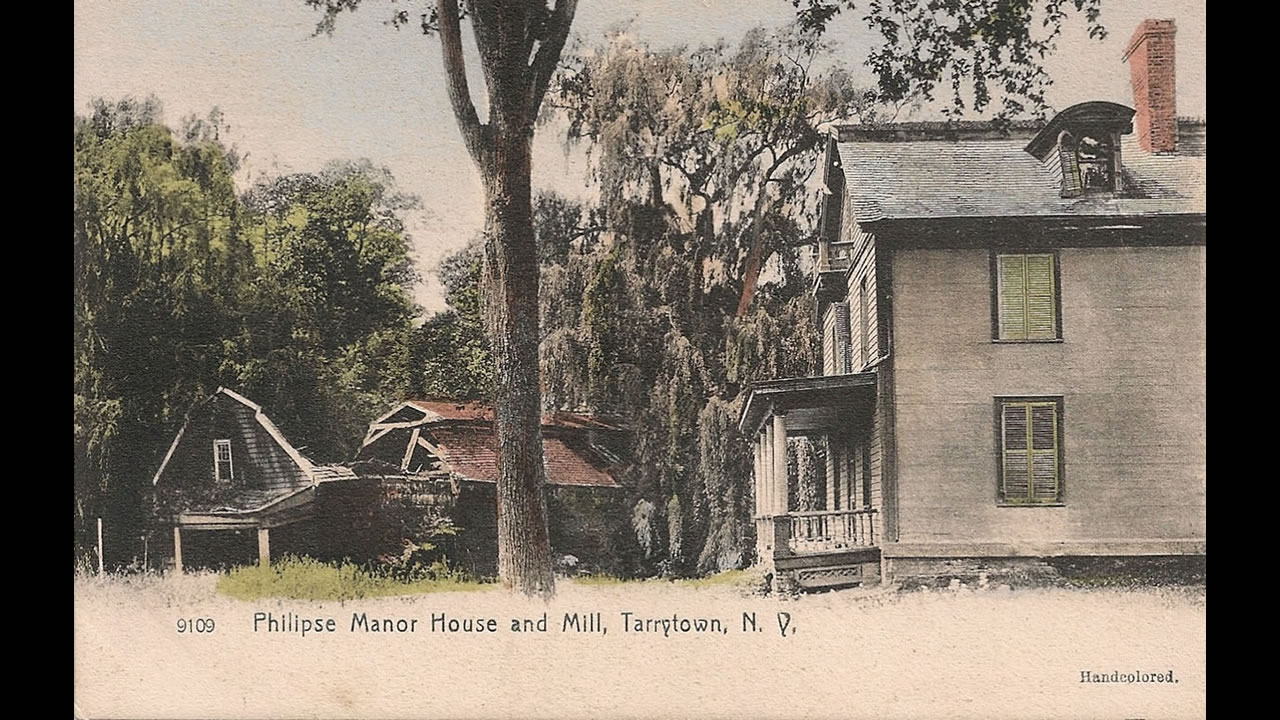

Sleepy Hollow, Sunnyside, and Irving's Architectural Dream for the Hudson Valley

Original two-room cottage built ca. 1656; land and house purchased by Washington Irving and house expanded beginning in 1835.

For Washington Irving, history, fiction and architecture were inexorably bound together. Irving left New York in 1815, before he wrote "Sleepy Hollow." Finishing his story in England, Irving was greatly influenced by Abbotsford, the stately home of author Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), whom Irving stayed with in Scotland for several days. The two men found each other kindred spirits, bonding over literature and the necessity to display tradition through architectural form. Scott purchased i Abbotsford in 1811 and extensively restored it utilizing materials and features from historic and ruined structures, creating the appearance of a much older Romantically-gothic castle. Irving was inspired by Scott's ability to suggest historic structures in a more modern dwelling. As cultural historian Duncan Faherty suggests, "The projects of the past were no untouchable artifacts but malleable elements to be blended into serviceable material."54 This blending of fact and fiction in architecture took root in Irving's head as he viewed the rustic, picturesque British landscapes whose villages were steeped in their own shared history and traditions.

F.O. Morris, Abbotsford, c. 1880. Source: Darvill's Rare Prints.

Irving was unaware that the America he would return to would be drastically different from how he left it. New York, he recalled, “had outgrown by recollection form its very prosperity, and strangers had crowded into it from every clime to participate in its overflowing abundance.”55 Despairing of New York, Irving purchased a plot of land with a small cottage in Tarry Town in 1835 and finished remodeling the house within the year. The small Dutch colonial cottage had originally belonged to John Van Tassel, who inspired the character of Baltus Van Tassel in "Sleepy Hollow." Irving altered greatly the Van Tassel House. He sharpened the roof’s pitch, clustered the chimneys in imitation of English rustic styles, rearranged the windows into an irregular style that would make the exterior appear more romantic, and had the plastering scored to create the illusion that Sunnyside was a cut stone building. Irving argued that cultural order stemmed from vernacular architecture, and that preserving and prioritizing the historic, rustic, and picturesque in houses would lead to a more cohesive social structure and a sense of settledness.

Right: Van Tassel's House. (Vide Legend of Sleepy Hollow) Recently purchased by Washington Irving, Esq. to improve for a Summer Residence, ca. 1832. Via NYPL Digital Gallery.

Furthermore, Irving added several Dutch-style weathervanes he had ‘rescued’ from demolished buildings in New York and Albany; they worked to appropriate earlier styles into Sunnyside’s structure in order to 'date' the house, but also acted as allegorical refugees, coming from historic houses that had been destroyed without thought of preservation. The final touch to Sunnyside was the “inscription stone,” which bore an engraving in Dutch stating the house had been erected in 1656, but reconstructed by Irving in 1835. To Irving, this resembled, “the dated wrought iron tie beams found on many colonial New York dwellings.”56 Here Irving attempted to authenticate Sunnyside, tying together the colonial Dutch history of the region and propagating the myth of a cultural heritage that was not yet lost. The house was meant to appear both Gothic while also recalling the Dutch houses of early Manhattan. Furthermore, its hybrid nature evoked the picturesque vernacular domestic architecture of Britain, part of an emerging trend to canonize historic homes that were aesthetically appreciated for their rustic, antiquated look. Ironically, Sunnyside operated, both in its conception, and by its reputation, as an anachronism within Tarrytown, adapting existing vernacular Dutch forms and appropriating features from the Romantic, Gothic and colonial traditions. With all its additions, the house had barely any relation to the original structure.

While historic preservation was a priority, Irving also believed that in order to create enduring relationships to their nation, people had to refashion their attachment to houses and nature. Essentially, national character could be located in domesticated landscapes, and the architecture already present in those landscapes.

Thus, Sunnyside became, in its own way, a character in one of Irving’s own stories come to life. Irving sought to stabilize history by constructing a home which would allow Americans to recall their almost lost pre-Revolutionary cultural and social framework. However, his methods reveal how his idea of history was itself was a narrative, and that, if Sunnyside embodied history, it was to both literally and figuratively house its fictionalized past. So then did the small stone Dutch cottage become “The preeminent antebellum architectural shrine in America.”57

The American landscape designer and author Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) called Sunnyside, “the beau ideal of a cottage orne.”58

The house contributed, along with George Washington's Mount Vernon and other historic sites, to the belief that architecture facilitated formation of a national identity. Downing acknowledged the diverse historic features of the estate, noting that the house partook “somewhat of the English cottage mode, but retaining strongly marked symptoms of its Dutch origin. The quaint old weather cocks and finials, the crow-stepped gables, and the hall paved with Dutch tiles, are among the ancient and venerable ornaments of the houses of the original settlers of Manhattan, now almost extinct among us.”59Irving’s fiction promoted the significance of historic houses, and he created a house that was in many ways fictional itself. In essence, the temporal confusion embodied in Irving’s narratives played out for him in real life. Irving constructed Sunnyside as an ode to the communities of his youth and those he constructed in his narratives: simultaneously circa-1815 and circa-1776. In December 1840, Irving wrote that Sunnyside, “attracted others…cottages and country seats have sprung up along the banks of the Tappan Sea, and Tarrytown has become the metropolis [of quite] a fashionable vicinity.60 The Hudson Valley became a popular destination for viewing picturesque old houses and landscapes.

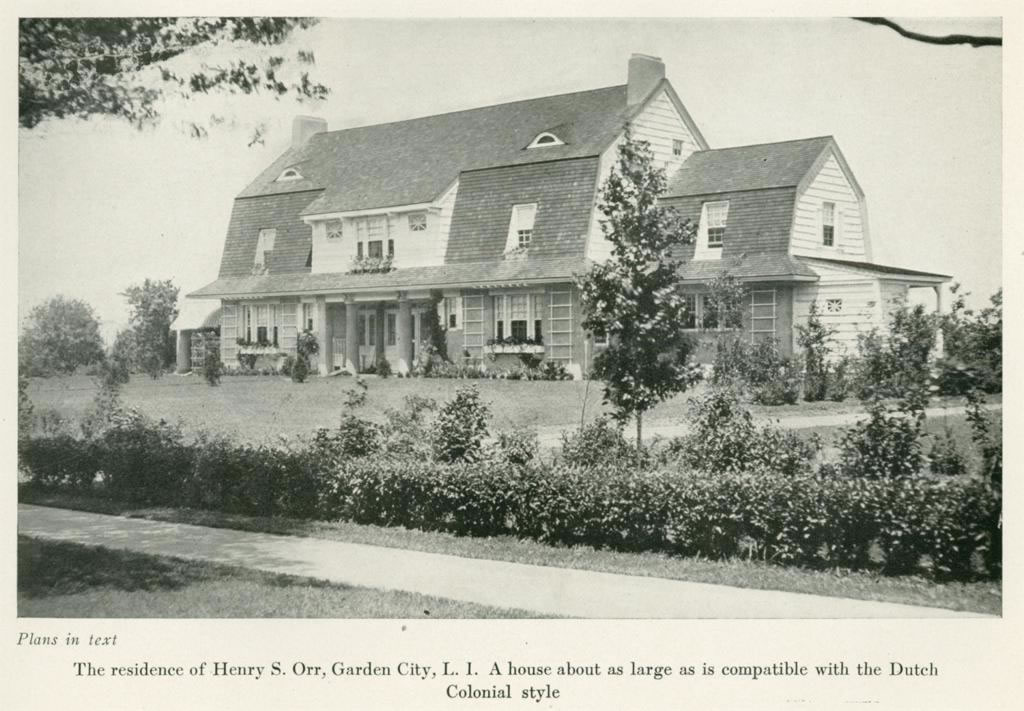

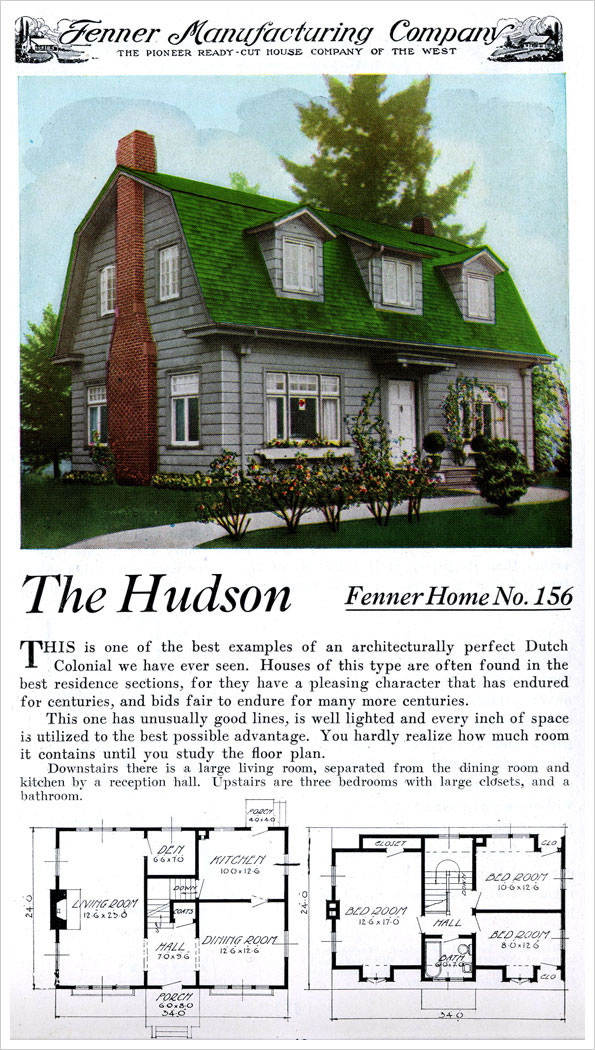

Irving's invocation of the spinning wheel and churner, symbols of both domesticity and tradition, help situate Dutch Colonial style within a larger discourse of the Colonial Revival. If Sunnyside typified the romantic, idealized Dutch Colonial house in the mid nineteenth century, the model resurfaced again in the early twentieth century as American families began to populate suburban areas. Along with other revival styles, Dutch Colonial architecture became a vernacular style of solid, middle-class living: “It was a large, commodious design with open space, a good relationship to its suburban site, plenty of room for family functions, and a strong, rationally, and pragmatically designed facade.”61 Not too ostentatious, its charming features drew upon a historic aesthetic, which appealed to many upwardly mobile couples attracted to a cottage-type house that looked as if it had been in the family for generations.

Right: Amityville House, Long Island, New York. Source: Getty Images.

Dutch Colonial style houses were popular in the 1910s and 1920s, and kit-manufactured homes by Sears or Fenner Manufacturing came with a fixed price for all materials needed, with everything already cut to fit and numbered. The most distinguishing features of a Dutch Colonial home were its gambrel roof and gable-end chimneys. According to the 1928 Home Builders Catalog, "The legend goes that this low, sweeping roof, with its dormer windows, was the ingenious means by which the Dutch Colonists evaded the heavy tax on two story houses. And there is today a practical advantage over the two story house in saving of materials without the loss of space."

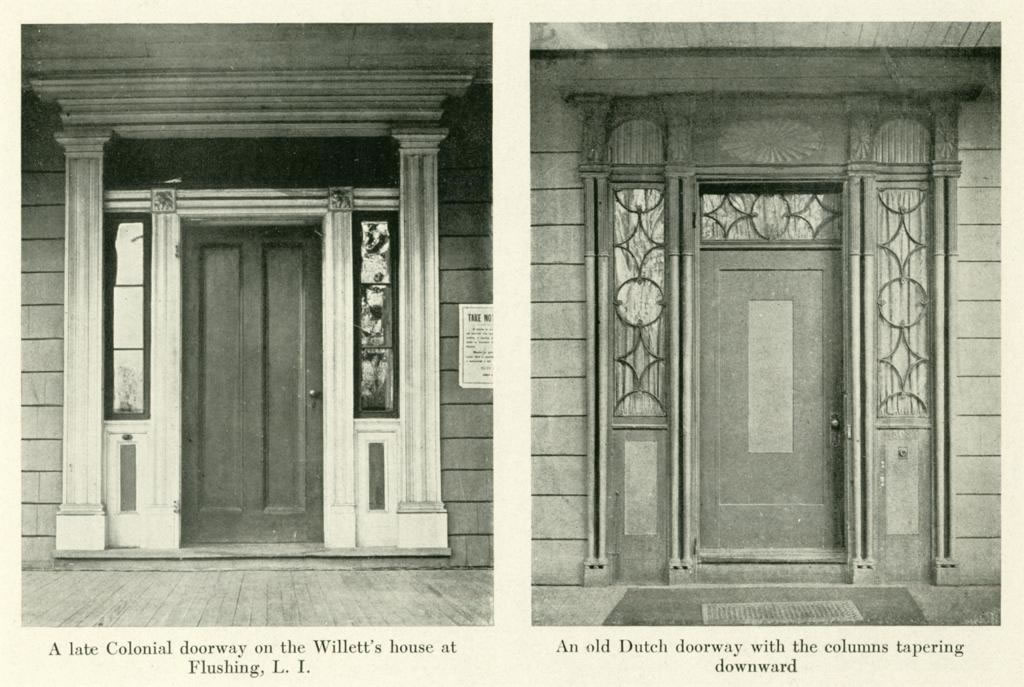

The Dutch Colonial aesthetic comes out of the settlement of the Dutch colony of New Netherland in 1614, established in New York and New Jersey, which soon enjoyed a thriving commercial base. Even when the English settled in 1664 and became the dominant cultural tastemakers, the Dutch maintained their traditions in the style of their houses, crafts, and folklore.

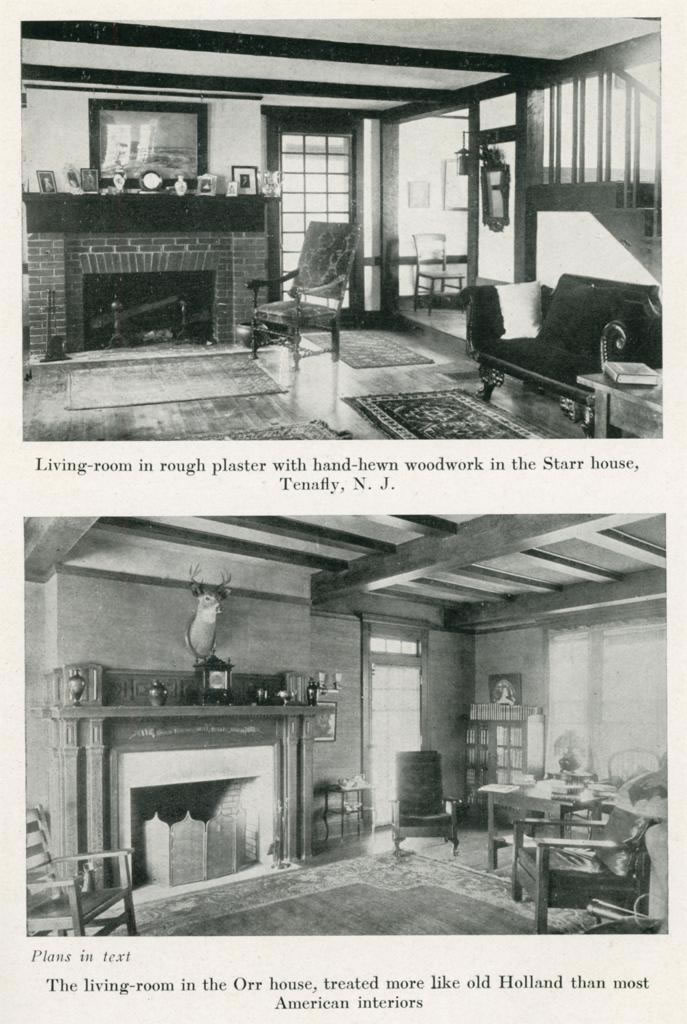

The Arts & Crafts movement in the early twentieth century sustained this colonial aesthetic through the production of furniture influenced by the handmade, sturdy look of Dutch models. Charles Limbert (1854-1923) was one such artisan whose "Holland Dutch" furniture found popularity. Arts & Crafts philosophies were not so far removed from the Dutch appreciation for materials, workmanship and individual endeavor. The Dutch "look" once more found prominence in American lives, this time in interior, rather than exterior, design.

In recent incarnations of the Colonial Revival, a desire for handcrafted goods and their associated antiquarian aesthetic has made Dutch Colonial Revival furniture trendy. Alienated from their original context, design scholar Max Tielman calls this movement a "Colonial Re-Mix," adding, “This is Colonial for the twenty-first century, Colonial that both celebrates the forward-thinking and hopeful world of today and mourns the loss of simpler, less overwhelming times.”

Right: Kast, c. 1700-1730, red gum, tulipwood, and pine. In Peter M. Kenny with Frances Gruber Safford and Gilbert T. Vincent, American Kasten: The Dutch-Style Cupboards of New York and New Jersey, 1650-1800 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991).

Evocation and (Be)Longing

Washington Irving's themes of memory, community and anxiety makes "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" a story about how one can both fear and long for the past. "Sleepy Hollow" can be read as an archetypal colonial arcadia: bountiful without capitalism, settled and content, and seemingly embedded in its own history. The mere mention of the tale triggered a feeling which Irving himself characterized as distorting, perhaps even malevolent. In his initial description of Sleepy Hollow, he speaks of the “witching influence of the air,” and that those who enter the region, “begin to grow imaginative—to dream dreams, and see apparitions.”

Irving invoked longing in his descriptions of the food, the landscapes and the native tradition of storytelling. He clearly valued the unchanging, perhaps even liminal, character of this Dutch community, in contrast to “the great torrent of migration and improvement, which is making such incessant changes in other parts of this restless country.” Yet this nostalgia was a double-edged sword. Implicit in the understanding of the gothic appeal of the story is that the Colonial period was fraught with doubt for what lay beyond their borders. Sickness, poor weather, failed crops and attacks from nearby tribes led to an almost constant tension within a community. This environment allowed for all manner of superstitions to become exaggerated, a fact that Irving notes in his Sketch Book: “In the early chronicles of these dark and melancholy [Colonial] times we meet with many indications of the diseased state of the public mind. The gloom of religious abstraction and the wildness of their situation among trackless forests and savage tribes had disposed the colonists to superstitious fancies, and had filled their imaginations with the frightful chimers of witchcraft and spectrology."62 Literary scholar Daniel Hoffman remarked, “Wherever Irving went he collected popular sayings and beliefs; he was prepossessed by a sense of the past, and recognized the power, and the usefulness to a creative artist, of popular antiquities.”63

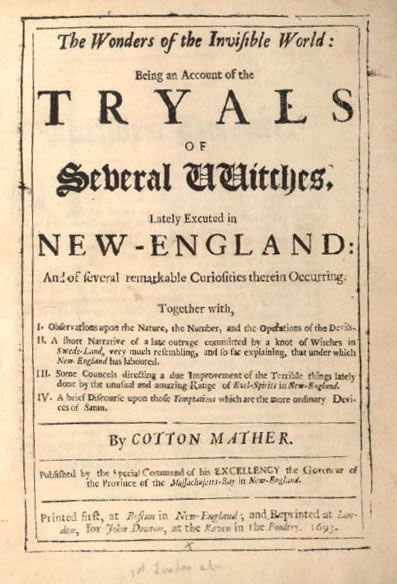

Ichabod Crane is an early model for the kind of gothic thrill-seeker that would later characterize fans of Irving's works. The character is enamored with the haunted properties of the New England landscape, and sees in Tarry Town comparative spooky thrill. “[He] was a perfect master of Cotton Mather’s History of New England Witchcraft, in which, by the way, he most firmly and potently believed…He was, in fact, an odd mixture of small shrewdness and simple credulity. His appetite for the marvelous, and his powers of digesting it, were equally extraordinary…No tale was too gross or monstrous for his capacious swallow.”64 His restless yearning for the haunted past ends up being his undoing, as the story climaxes with a fateful encounter with the Headless Horseman, believed to be the ghost of a Hessian Soldier, “whose head had been carried away by a cannon ball,” and is a very potent reminder of America's pre-Revolutionary era.

Irving's “Sleepy Hollow” was a metaphorical gateway to an invented past, where one could easily lose their way and forget reality. The story would later be placed under the umbrella of Gothic Fiction, a genre emerging in the early nineteenth century alongside Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) and Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849), engendered with a sense of romanticism and excitement.

The gothic and picturesque appeal of Sleepy Hollow and Irving’s other Dutch tales proved an enduring draw for tourists and travelers, who flocked to the Hudson Valley to seek for themselves Irving’s “Legend.” Attempts were made to distinguish fact from fiction, such as the search for “Rip’s Cottage” in the Catskills. More popular was trend of reading “Sleepy Hollow” within the landscape surrounding Tarry Town. Writers of the 1838 Sketches of the North River recommend that, “only in such a region, with the grand and terrible around you…it can be read with the most zest; seated upon a lonely rock in some dark dell, you become imbued with the spirit of its conceptions.”65 Irving’s tales became indistinguishable from the regional culture of the Hudson Valley, once more distorting the nature of his authorship. Were his works really fiction? Or was Washington Irving, like his nom-de-plume Deidrich Knickerbocker, a folklorist recounting tales that had existed in America’s haunted past since the nation’s inception?

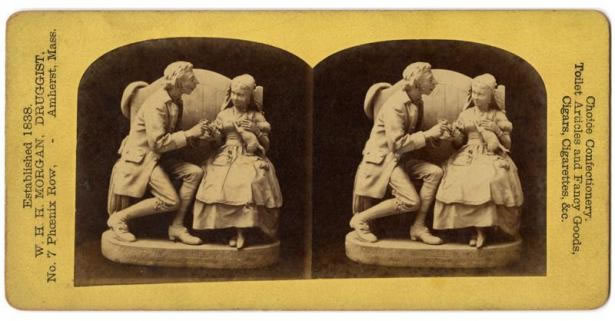

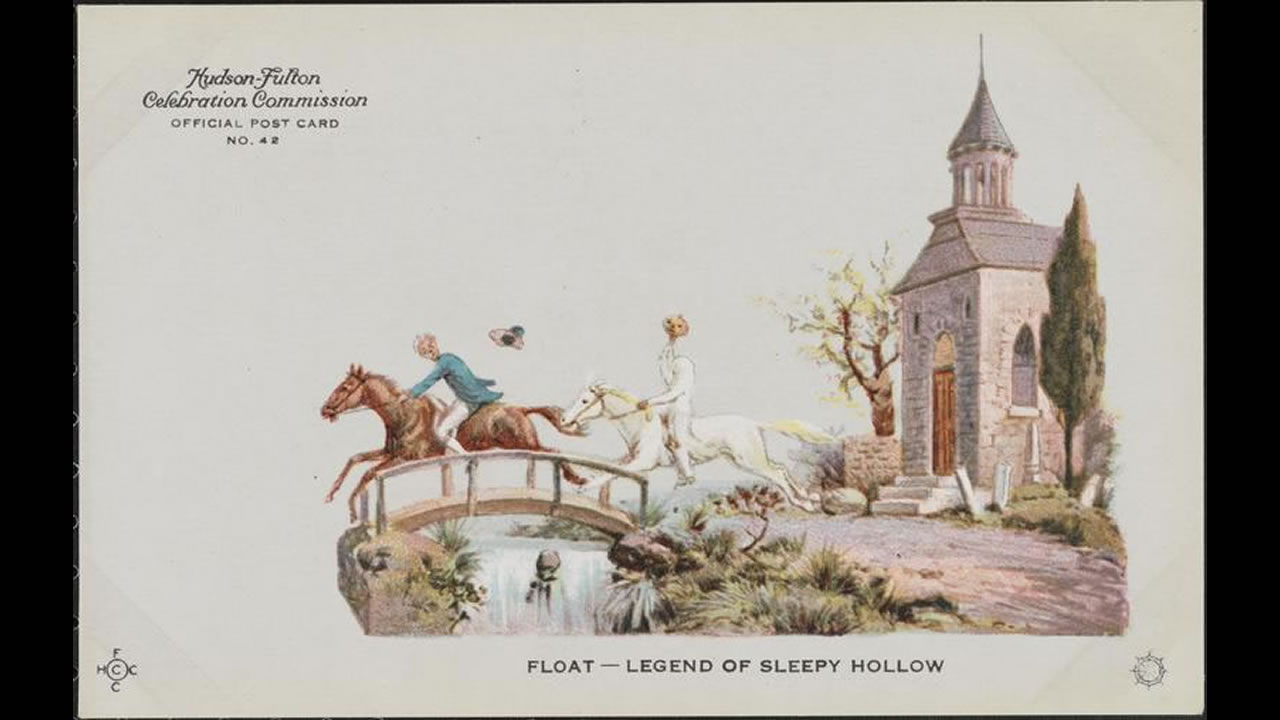

Once more, Irving’s influence can be seen in the multiple modes of artistic and cultural forms that proliferate around “Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle” at the turn of the century, geared towards tourism. Postcards, stereographs, ephemera and memorabilia document the "haunted" appeal of Irving's fiction, which became synonymous with the region.

Right: John Rogers, Ichabod Crane and the "Headless Horseman," 1887, bronze, 35 x 48 x 29 in. Source: New-York Historical Society.

While Sunnyside and historic preservation marked an early attempt to boost tourism in the Hudson Valley, the branded gothic appeal of "Sleepy Hollow" more readily attracts modern-day visitors.

On the Town of Sleepy Hollow's website, the text proclaims "Where the Legend Lives." North Tarry Town was renamed Sleepy Hollow in 1997 to rehabilitate the town's image after decades of industry and the shut-down of a General Motors plant had given the area a negative reputation. According to a 1996 New York Times article, town residents' desire to boost their economy through tourism was the incentive for the proposed name change. The understanding was that Sleepy Hollow would, "revitalize the town by giving it a fetching name that would bring in tourists, homebuyers and investors." Those who resisted the change claimed that it was an "empty, pretentious gesture" that would do little to attract those who were interested in Washington Irving or the legacy of his tale.66

Today, Sleepy Hollow enjoys a thriving tourism industry, boosted by recent pop-culture revitalizations of Irving's narrative and the trend for frequenting sites with connections to hauntings and ghosts. In 2006, a large statue was erected on the town's Green depicting the Headless Horseman chasing Ichabod Crane, which provided a visual link between the Town's tourism-driven mission and the "Legend of Sleepy Hollow" as a text which evoked longing for gothic, atmospheric imagery.

North Tarry Town's makeover into Sleepy Hollow makes it a frequent tourist destination and provides an avenue to revive other Dutch colonial traditions, such as the open-hearth cooking demonstrations, hands-on activities, and child friendly crafts including corn-husk doll making, as well as Green Corn Festival, a Native American harvest festival featuring traditional song and dance and games.

On a smaller-scale, online marketplaces such as Etsy.com promotes handmade goods and a “homespun” aesthetic. One can purchase Sleepy Hollow-inspired candles, jewelry and jam, with labels often utilizing the motifs of a cemetery, silhouetted bare trees, and the headless horseman.

Irving on Film

Irving’s Sleepy Hollow continued into the late twentieth, and early twenty-first century. Popular culture reshaped the narrative to focus on its gothic imagery and spooky appeal.

(Articulation of) Temporality

Right: Leonard Everett Fisher, ”The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” 10-cent stamp, American Folklore series, 1974, 1.44 x 0.84 in. Source: ebay.com.

If we understand the Colonial Revival as a process of continually looking back toward the past and ahead toward the future, Washington Irving's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" embodies both the themes and issues at work in the movement.

A dominant interpretation of Sleepy Hollow argues that the Headless Horseman represents the duality of American memory. On one hand, he comes from a recognizable past, a past shaped by the Revolutionary War and the resulting formation of an American history. On the other hand, the very nature of regional ghostlore, explained literary scholar Judith Richardson, reflects disorientation, uncertainty, discontinuity, and unrootedness.67

The Horseman keeps history ‘alive’ in Tarry Town by being dead, and also serves as a reminder that the past is at times opaque, and open to interpretation. The Dutch see him as their own, sewn into the traditions of their community. Ichabod Crane views him with an excitement and terror that is born from an all-consuming hunger, a hunger that yearns to erase or selectively remember history. Just as traditional ghost stories were allegories of the anxieties of close-knit groups towards strange places and people, so was Ichabod Crane the real "ghost" of Sleepy Hollow, haunting the region. His presence allowed for Irving to reflect on the effects his Yankee brethren would have on the locally-based effort to preserve historic continuity. But even this effort, contains within it its own kind of selective collective memory. America's attempts to distinguish their particular history often served negatively to distance one’s own experience to their past. This temporal disorientation is a device Irving draws upon in his opening to “Sleepy Hollow,” where he has Geoffrey Crayon describe the story as a tale told “in a remote period of American history, that is to say, some thirty years since…” Furthermore, it is clear that at the end of the story it is Brom Bones who attacks Crane; however, the encounter soon becomes an old wives tale, seamlessly fitting into the existing folklore of the region and Sleepy Hollow legend. Having just happened, it is already a relic of the past.

Irving's stories embraced the duality felt by his readers: how can one honor the past and tradition whilst simultaneously crafting a history in the present? The editor of an 1874 Dutchess County book Local Tales and Historical Sketches articulated the problems experienced by Dutch communities who were being faced with the Ichabod Cranes of the world: “We are drifting along with scarcely an effort to preserve from fast approaching oblivion the thousands of interesting facts, recollections, and reminiscences of the past, relating to our country.”

Certainly the Colonial Revival can be regarded as a movement to preserve the past, but it also serves as an Irving-esque device of continual re-telling of a story until it becomes truth. In the postcript to Sleepy Hollow, Irving (as Mr. Knickerbocker), relays that he first heard this tale (within a tale), in a meeting of corporation gentleman in Manhattan. The narrator concludes his tale to the mirth of the audience, except for one objecting listener who doubts the veracity of the story and challenges the storyteller. In an ingenious stroke, which captures the very duality illustrated above, the storyteller replies, “Faith, sir…as to that matter, I don’t believe one-half of it myself.”

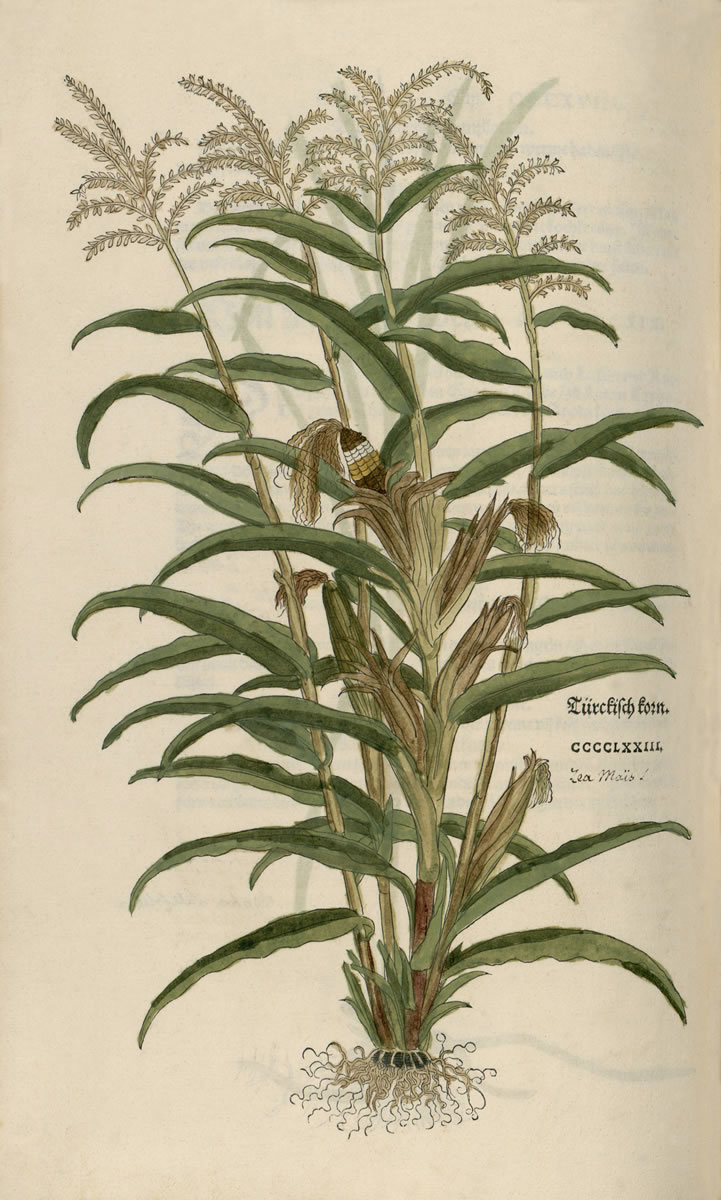

Indian Corn

If the central object of this project is to make the invisible Colonial Revival visible, Indian corn is an excellent place to start. Corn is all around us; widespread consumption of high fructose corn syrup has rendered most of the calories Americans consume corn derivative.68 Facing the ubiquity of corn in the United States, one may not think it has anything to do with the Colonial Revival. Looking at case studies of corn at world’s fairs and expositions, the campaign to make corn the national flower, and its role in Thanksgiving, illuminates the place of Indian corn in the Colonial Revival. Here corn is a tool to understand what the “Colonial Revival” means, and how that meaning has changed from the latter nineteenth century to today.

Indian Corn

Indian corn is the name given by English Colonists to the grain known as maize.69 Maize was first brought into the territory that later became the United States circa 700 AD.70 Maize therefore was well-established before the period of exploration and colonization by Europeans. In “Translating Maize into Corn: The Transformation of America’s Native Grain,” Betty Fussell argues that the distinction between corn and maize comes with colonial use, rather than difference in grain composition.71 Under this explanation corn is colonial.

The English term “corn” originally included grains of all kinds, even grains of salt (hence "corned beef").72 “Turkey corn” and “Indian corn” were used by the English to mean any “uncivilized” grain.73 It was not until Linnaeus’ categorizations that the term Zea mays was given to the plant family known as maize.74 The term “Indian corn” was used as early as 1604, though what became known as Indian corn was published in Europe as early as 1597 under the name “Turkey wheat” (three colors were listed in this publication, “yellow” “blew” and “red.”)75 Today hard-kernelled corn in the United States is known as maize or Indian corn, in contrast with soft-kernelled corn called corn or sweet corn.

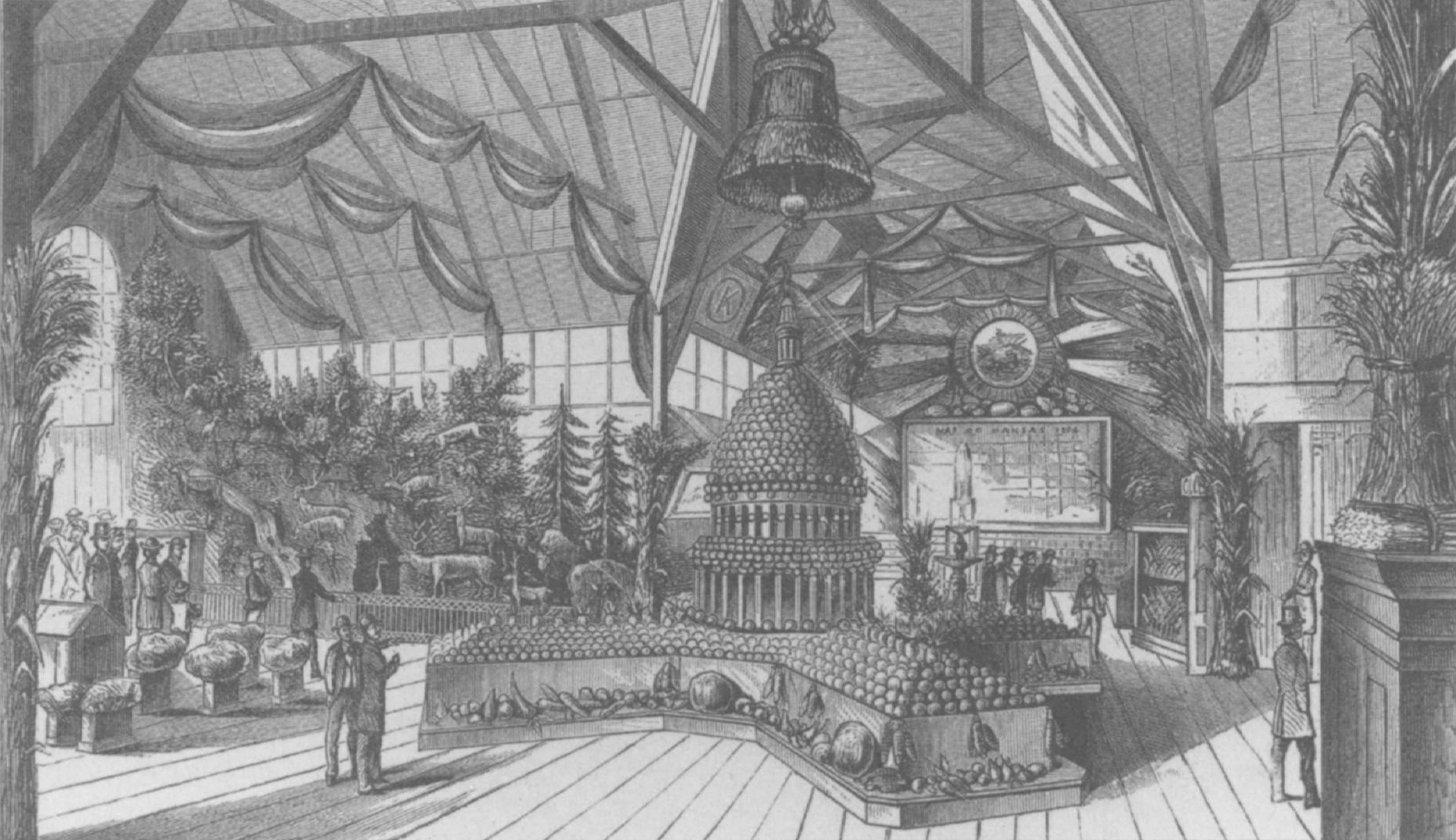

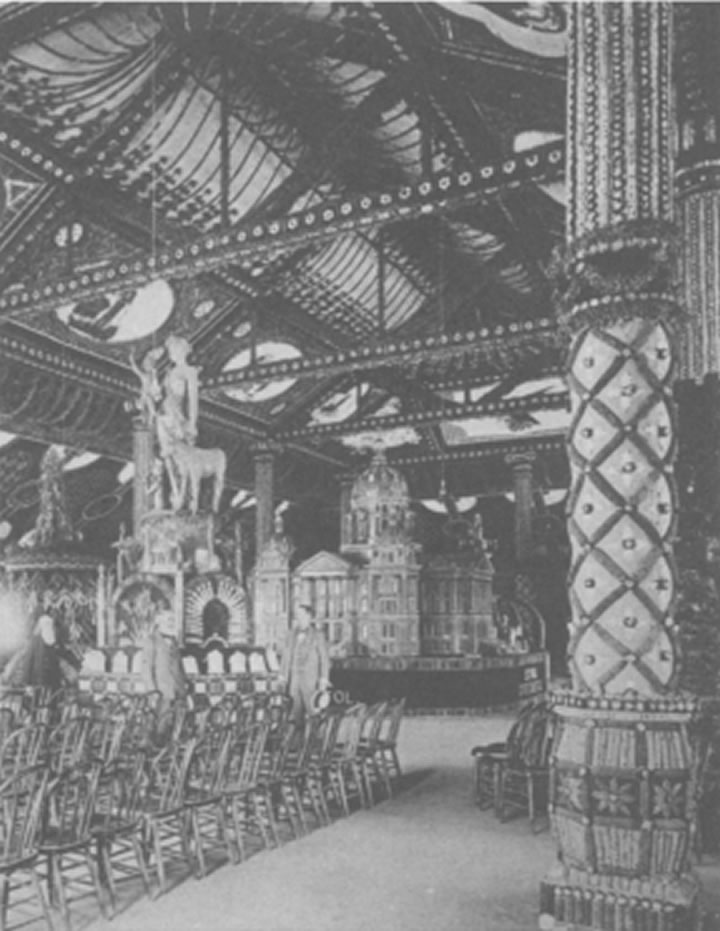

Display Corn

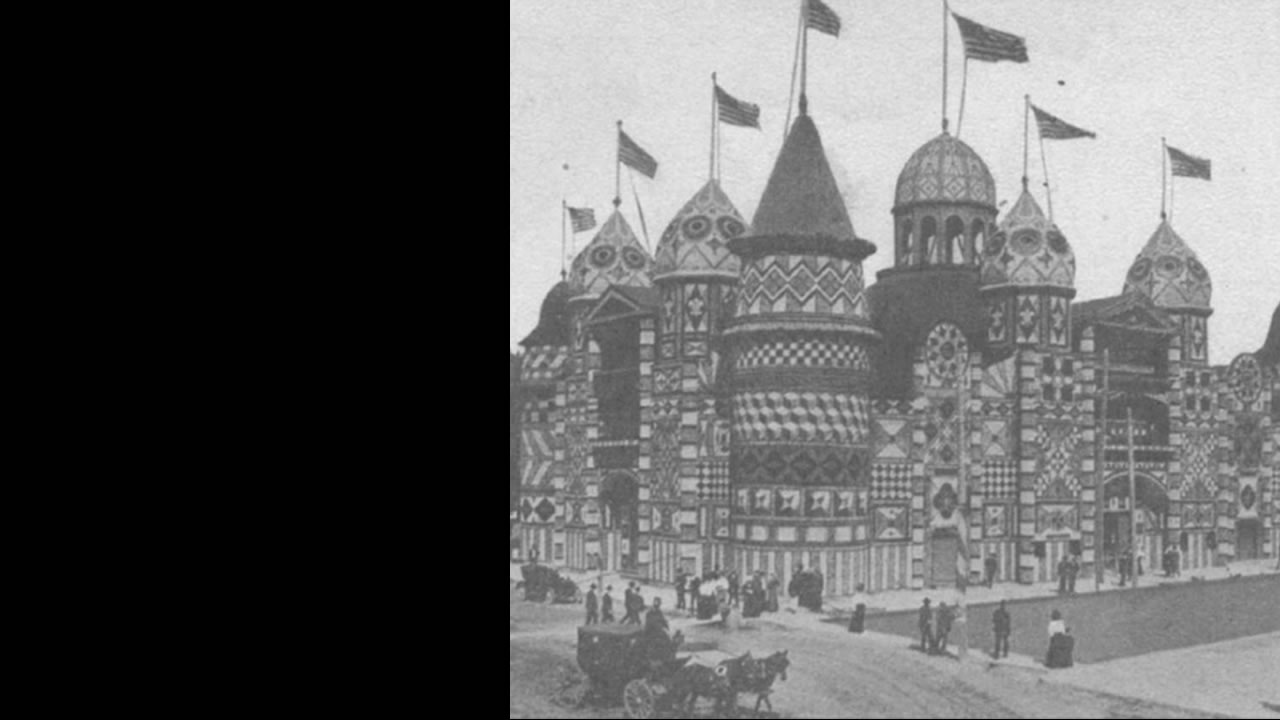

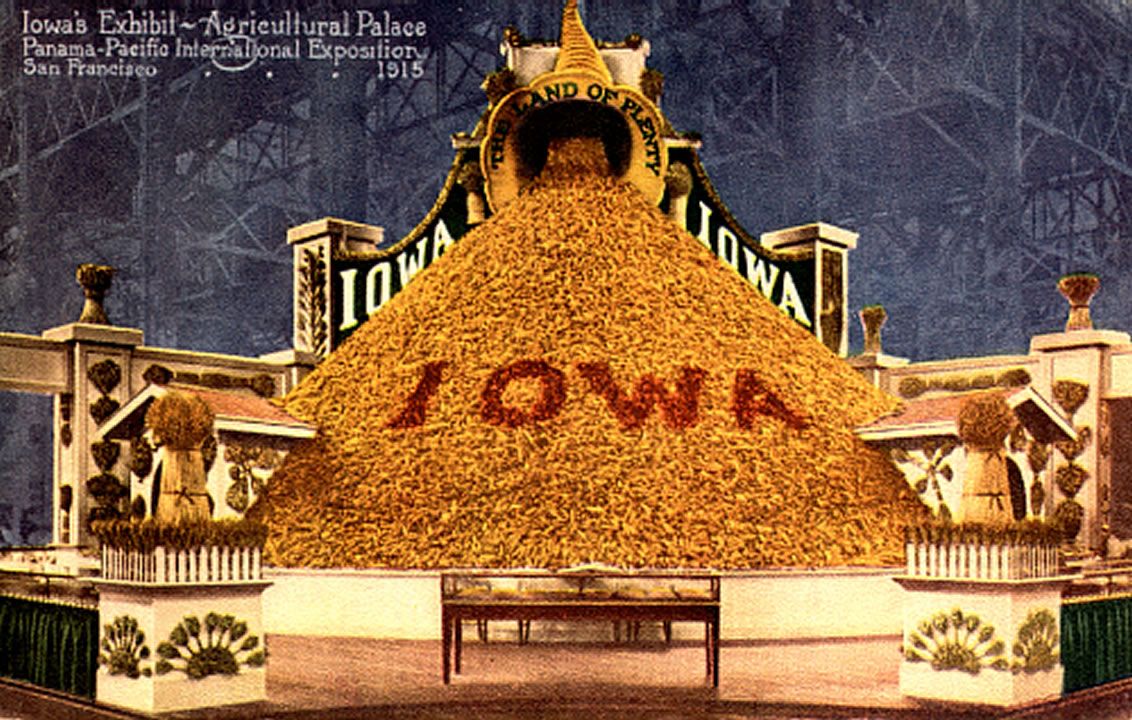

The Liberty Bell was made in 1751 for Pennsylvania’s State House with an inscription speaking to the freedoms of that colony.81 The old State House bell was renamed the “Liberty Bell” by abolitionists and adopted as a symbol of their movement.82 Toward the end of the nineteenth century the Liberty Bell traveled to exhibitions around the country, becoming a prominent Colonial Revival object.83 At the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition, most Midwestern states presented some version of crop art.84 Iowa’s display was particularly dramatic.

The seemingly sudden trend of corn and other agricultural art at the Columbian exhibition was the result of the preceding popularity of corn palaces.85

Wheeler’s second description seems to refute Blanchard’s view, as it celebrated corn within the traditional idiom of the pioneer movement and uses a conventional narrative of European settlers civilizing the wilderness. In her final use of a corn vignette, Wheeler described an accomodationist vision of the South. Slavery meant a “happy South” where the slave-owning class was “patriarchal” and “hospitable,” in contrast to the post-Civil War South.99

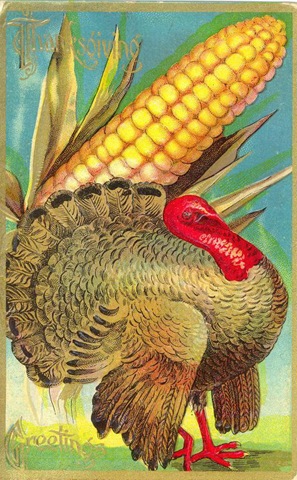

Thanksgiving

During the early twentieth century, corn became associated with Thanksgiving, both gastronomically and symbolically. However, the holiday itself only gained prominence less than a hundred years earlier, and corn did not appear regularly on its mealtime menu. Thanksgiving was not an established holiday in the colonial period and became more consistently celebrated in the early nineteenth century as a regional New England event.102 The idea of the Pilgrims' “first Thanksgiving” was popularized by Alexander Young’s 1841 publication of a 1621 letter, which described a feast at Plymouth plantation attended by ninety Massasoit men.103

The poet Sara Josepha Hale was instrumental in making Thanksgiving a national holiday.104 Hale wrote Northwood; or, a tale of New England comparing life in the North and the South of America.105

The novel discussed the question of slavery; it also included a long description of a Thanksgiving dinner as part of New England life.106

Right: In this image the beautiful Native American woman is aestheticized, she wears a Japanese looking dress, she gazes into a cornfield to appreciate its beauty. Her skin is white.

Hale includes a variety of foods in her description of Thanksgiving. Some, such as turkey and pumpkin pie, have remained traditional Thanksgiving foods, while goose, pork, beef, chicken pie, plates of pickles, plum pudding, and sweetmeats would be unconventional at a Thanksgiving meal today.111 Corn does not have a prominent place in Hale’s Thanksgiving, but became more so with the regularization of Thanksgiving food during the early twentieth century.

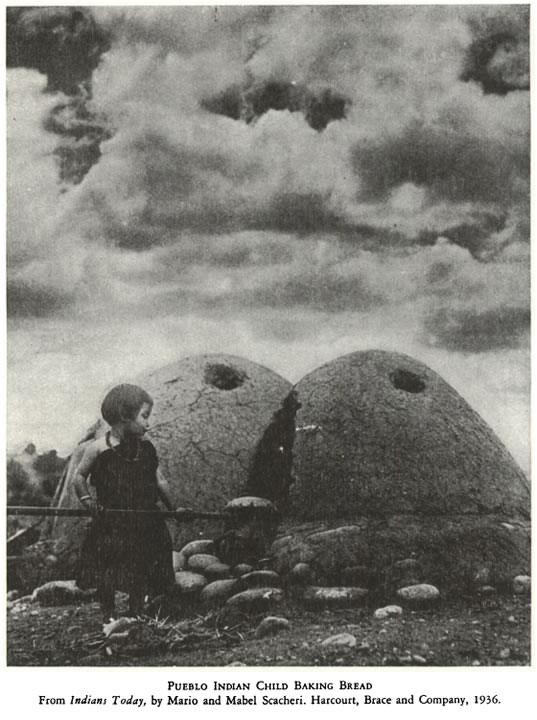

Throughout the 1950s the Science News-Letter published a number of articles on Thanksgiving foods and origins. These writings identified and promoted the use of “distinctively American” foods, and celebrated the Native American contribution to the first Thanksgiving. In a 1951 article, “Thanksgiving is All-American,” Watson Davis argued that one should set an “All-American holiday table” through including “Turkey, cranberries, sweet-potatoes, pumpkin, corn bread,” all cast as foods of American origin.117 In this article, Davis called corn “the greatest of the agricultural gifts of America to the world.” He also described the colonial period, writing, “Our history books tell us how corn, cached by Indians of the region, saved the Plymouth Colony during the terrible first winter of 1621.”118 Though the Native Americans are not figures of strangeness or blame here, neither are they real agents in this story. Their cache of corn saved the pilgrims, not them.

A 1955 article appearing in the same Science News-Letter, “Pilgrims Thanksgiving Gold” by Horace Loftin, elaborated on corn’s role at Plymouth. It recounted the story of the pilgrims finding a store of corn and then went on, “The Pilgrims had hit upon one of the food caches of the Wampanoag Indians, whose country they had invaded and called Plymouth Colony.”119 This article presented a seemingly progressive view of settler and Native American interaction. By promoting a largely positive account of indigenous people' contribution to the Pilgrims' survival. Yet it elides acknowledgement of the Native American genocide.

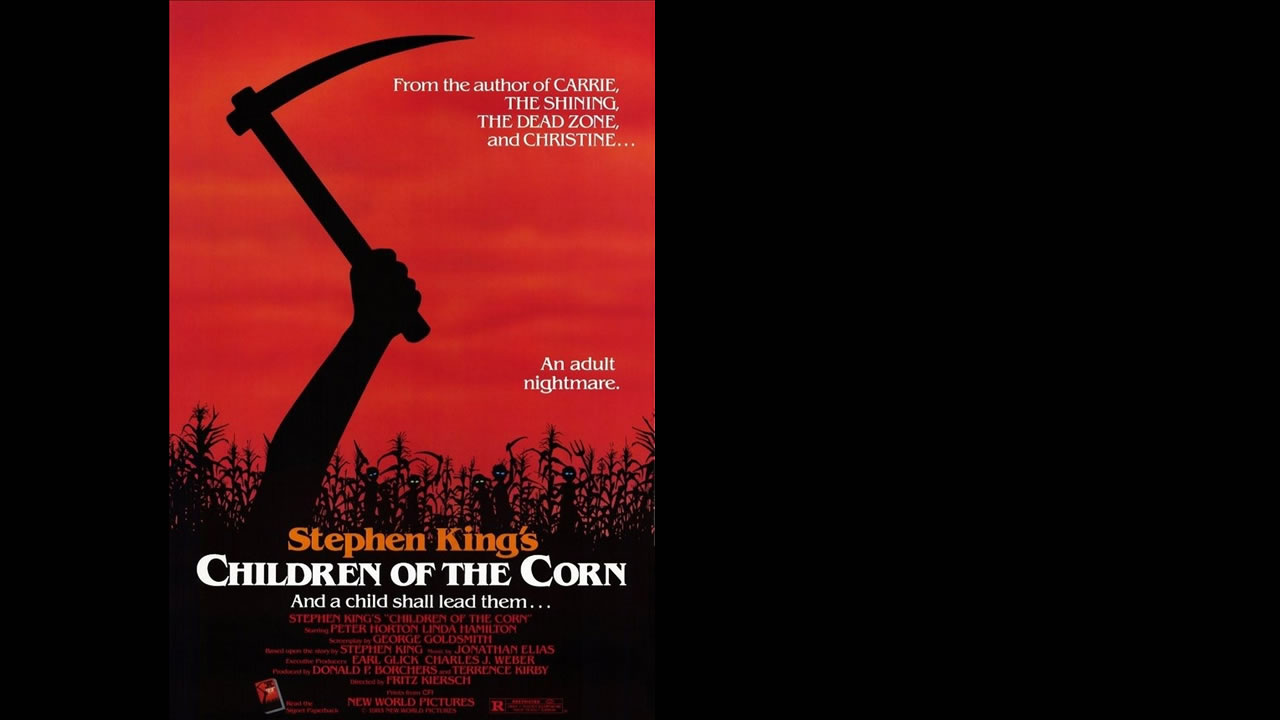

Children of the Corn

Stephen King first published his short story “Children of the Corn” in the March 1977 issue of Penthouse, the year after the U.S. Bicentennial. "Children of the Corn" takes place in a rural community where all the adults have been killed and the children live in theocracy devoted to the worship of a devil living in the cornfields. They readily sacrifice an adult couple that has mistakenly driven into their community.

The answer to that question has changed through time. The work of Oscar Howe, a Dakota Indian of the Yanktonias tribe, as a designer of the Mitchell Corn Palace murals from 1948 to 1971 points to the need for nuanced interpretations of Indian corn and Native Americans in the Colonial Revival.121 Such complexity cloaks the visibility of Indian corn as a Colonial Revival object.

Conclusion

This scholarship presents the Colonial Revival as ongoing and multi-faceted, a persistent manifestation of object-based cultural nationalism. Collaborators began by conceptualizing the project as an exhibition in and of digital media, presented as both a sequential narrative but also navigable by themes. The format allowed for a variety of intellectual strategies within the case studies. While some contributors closely attended to their central objects and moved outward to broader contexts, others more quickly took their artifacts as jumping-off points for wide-ranging multimedia investigations. Taken together, these case studies demonstrate, we hope, the utility of multiple approaches to interpreting the complicated interrelationships of material things and immaterial values in synergistic ways that may serve as productive points of departure for further exploration of the slippery phenomenon that is the Colonial Revival.

Produced by Kimon Keramidas, Assistant Professor and Director of the Digital Media Lab, Bard Graduate Center and Andrew Gardner, BGC Student and Digital Media Lab Assistant.

Endnotes:

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg Reproductions: Interior Designs for Today's Living, (Craft House, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1973), 10.↩

- Foley, Tricia, and Catherine Calvert, Williamsburg: Decorating With Style (Clarkson Potter: Williamsburg, VA, 1998), 17.↩

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg Reproductions, Craft House, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1982.↩

- Ibid.↩

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg Reproductions: Interior Designs for Today's Living, (Craft House, Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1973), 24.↩

- Ibid.↩

- The first major publication on Buckland Rosamond Randall Beirne and John H Scarff's William Buckland, 1734-1774; Architect of Virginia and Maryland was published in 1958 by Maryland Historical Society. 2.↩

- Karin Remesch, "Behind the Scenes: Hammond-Harwood House" The Baltimore Sun, February 28, 1999: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1999-02-28/entertainment/9902280321_1_harwood-house-william-buckland-house-museum↩

- Petition for Inclusion – National Register of Historic Landmarks PDF↩

- http://www.hammondharwoodhouse.org/index.php?id=33↩

- Rudolf Wittkower, Palladio and English Palladianism (London : Thames and Hudson, 1974), 75.↩

- Pierre Le Muet, Traicté des cinq Ordres d’Architecture … traduit du Palladio Paris 1645; reprinted 1647.↩

- Wittkower, 78.↩

- Ibid, 83.↩

- Calder Loth, “Palladio’s Influence in America” ↩

- Luke Beckerdite “Architect-Designed Furniture in Eighteenth-Century Virginia: The Work of William Buckland and William Bernard Sears.". Leoni published his translations of Palladio separately between the years 1716 and 1720. The first combined edition was released in 1721. ↩

- Pearre, A. Y.. “A Museum by Chance; The Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis). Antiques, (1953) 63, 338-341. ↩

- Pearre, A. Y.. “A Museum by Chance; The Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis). Antiques, (1953) 63, 338-341.↩

- “The Harwood House,” The Baltimore Sun, Sept. 4 1926.↩

- Patricia Heintzelman, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form” 7/30/1974. ↩

- James D. Kornwolf, Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America, Volume 1(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 745. ↩

- Ellicott H Worthington, letter to A. W. Clark, October 18, 1927. ↩

- Annapolis: Hammond-Harwood House, 1783-1784, by Thomas Jefferson. N1; K107 and N527; M10 [electronic edition]. Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive. Boston, Mass. : Massachusetts Historical Society, 2003. http://www.thomasjeffersonpapers.org/ ↩

- St. John’s College, Annapolis Maryland, and It’s Environment of American History and Art. ↩

- Carter C. Lively’s presentation. ↩

- Montechello’s original design was based on Villa Cornaro in Piombino Dese, Italy, in Book II, Chapter XV of I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura. According to the Hammond-Harwood House website, “the plate of the Villa Cornaro follows the Villa Pisani plate; and directly opposite the Villa Cornaro in some 18th century English transcriptions of the work.” ↩

- Mystic Chords of Memory, 25, note 34. ↩

- David Gebhard, “The American Colonial Revival in the 1930s,” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 22, No. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn, 1987), 109; citing Claude H. Miller, “Building and Early American Home,” Country Life (New York) 57, no. 4 (April 1930): 41. ↩

- Harold R. Shurtleff, “Reply to Frank Lloyd Wright on Williamsburg,” Boston Transcript, December 3, 1938, pt. 5 p. 5.↩

- Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory trans. Lewis A Coser (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), ?. ↩

- Quoted in John Taylor Boyd Jr., "The Classical Spirit in Our Country Houses," Arts and Decoration 31, no. 4 (October 1920): 62.↩

- Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory, 24. ↩

- Avery, C. Louise. “The Clearwater Collection.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 29, no. 6 (June 1, 1934): 90–98.↩

- Falino and Ward : J. Falino and G. Ward, Silver in the Americas,1600-2000 (Boston: MFA, 2008): 343-44.↩

- Rogers, Meyric R. “A Revere Teapot.” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) 38, no. 3 (March 1, 1944): 38–41. doi:10.2307/4116586.↩

- Hipkiss, Edwin J. “The Paul Revere Room.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, 29, no. 175 (October 1, 1931): 84–88.↩

- William B. Rhoads, “The Colonial Revival and the Americanization of Immigrants,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Axelrod, pp. 341-361.↩

- Falino and Ward.↩

- "Revere-Jarvie Silver," Art and Progress, Vol. 5, No. 10 (Aug., 1914), 369.↩

- Fine Arts Journal, 29 (Dec., 1913) 723-24.↩

- Ibid, 733.↩

- Ibid, 729.↩

- Ruth Suckow, “The Folk Idea in American Life,” Scribner’s Magazine 88 (September 1930): 245-55; reprinted in Folk Nation: Folklore in the Creation of American Tradition, ed. Simon J. Bronner (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 2002), pp. 145-160.↩

- Norman S. Rice, Albany Silver, 1652-1825 (Albany: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1964).↩

- Beth Wees and Medill Harvey, Early American Silver in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: MMA, 2013. See also, Norman S. Rice, Albany silver, 1652-1825 (Albany: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1964. ↩

- Sam Binkley, "Kitsch as a Repetitive System: A Problem for the Theory of Taste Hierarchy," Journal of Material Culture (2000) 5: 135-136 ↩

- Pierre Munor Irving, From the Life and Letters of Washington Irving, 1869, 335. ↩

- Washington Irving, The Sketch-book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent (New York: G.P. Putnam and Son, 1868), 426. ↩

- Irving, The Sketch-book of Geoffrey, 470. ↩

- Anthony, "'Gone Distracted': 'Sleepy Hollow,'" 116. ↩

- Irving, The Sketch-book of Geoffrey, 457. ↩

- Anette Stott, Holland Mania: The Unknown Dutch Period in American Art and Culture (n.p.: Overlook, 1998), 270. ↩

- Stott, Holland Mania: The Unknown, 270. ↩

- Duncan Faherty, Remodeling the Nation: The Architecture of American Identity, 1776-1858 (n.p.: UPNE, 2009), 97. ↩

- Faherty, Remodeling the Nation: The Architecture,93. ↩

- Faherty, Remodeling the Nation: The Architecture, 103. ↩

- Faherty, Remodeling the Nation: The Architecture, 100. ↩

- Andrew Jackson Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (n.p.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1850), 51. ↩

- Downing, A Treatise on the Theory, 491. ↩

- Faherty, Remodeling the Nation: The Architecture, 107. ↩

- Herbert Gottfried, American Vernacular Buildings and Interiors, 1870-1960 (n.p.: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), 184. ↩

- Irving, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey, 289. ↩

- Hoffman, "Irving's Use of American," 427-428. ↩

- Irving, The Sketch-book of Geoffrey, 462. ↩

- Richardson, Possessions: The History and Uses, 67. ↩

- NY Times Article ↩

- Judith Richardson, Possessions: The History and Uses of Haunting in the Hudson Valley (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982),26. ↩

- Michael Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals (New York, NY: Penguin Press, 2006), 23.↩

- Betty Fussell, “Translating Maize into Corn: The Transformation of America’s Native Grain,” Social Research 66:1 (Spring 1999), 42.↩

- Fussell, 48.↩

- Fussell, 43.↩

- Fussell, 42.↩

- Ibid.↩

- Ibid.↩

- Fussell, 43.↩

- John Winthrop esq. The History of New England from 1630 to 1649. With Notes by J. Savage (Google eBook), S79.↩

- Fussell, 49.↩